Continuing Education in

the Health Professions

Proceedings of a Conference

Chaired by Suzanne W. Fletcher, M.D., M.Sc.

Edited by Mary Hager, Sue Russell,

and Suzanne W. Fletcher

, M.D., M.Sc.

Continui ng Educ ation in the Health Profess ions

Fl etcher

The Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation is a private philanthropy dedicated to improving

the health of individuals and the public. Since its establishment in 1930, the

Foundation has focused its support principally on projects and conferences

designed to enhance the education of health professionals, especially physicians.

ISBN 0-914362-49-6

This monograph is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without

permission. Citation, however, is appreciated: Hager M, Russell S, Fletcher SW, editors.

Continuing Education in the Health Professions: Improving Healthcare Through

Lifelong Learning, Proceedings of a Conference Sponsored by the Josiah Macy, Jr.

Foundation; 2007 Nov 28 - Dec 1; Bermuda. New York: Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation;

2008. Accessible at www.josiahmacyfoundation.org

A Conference Sponsored by the

Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation

Chaired by Suzanne W. Fletcher, M.D., M.Sc.

Bermuda

November 2007

Edited by Mary Hager, Sue Russell,

and Suzanne W. Fletcher, M.D., M.Sc.

Published by the

Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation

44 East 64th Street

New York, NY 10065

www.josiahmacyfoundation.org

2008

Continuing Education in

the Health Professions:

Improving Healthcare

Through Lifelong Learning

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 1

Preface …………………………………………………………………… 4

Introduction ……………………………………………………………… 7

Chairman’s Summary of the Conference ……………………………… 13

Conference Participants ………………………………………………… 24

Conference Images ……………………………………………………… 26

I. APPROACHES TO KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT—

WHAT WORKS AND WHAT DOES NOT ………………………… 29

How Physicians Learn and How to Design Learning

Experiences for Them …………………………

—Donald E. Moore, Jr., Ph.D. …………………………………… 30

Transforming Continuing Medical Education Through

Maintainence of Certification ………………

—F. Daniel Duffy, M.D. ………………………………………… 63

Discussion Highlights ………………………………………… 77

Internet Continuing Education ………………

—Denise Basow, M.D.…………………………………………… 82

Informatics Skills Needed! ………………………

—Donald A.B. Lindberg, M.D. ………………………………… 92

Remarks ……………………………………………

—David C. Slawson, M.D. ……………………………………… 94

Discussion Highlights ………………………………………… 98

II. FINANCING CONTINUING EDUCATION: ………………………

WHO, HOW, A ND WHY……………………………………………… 103

Financial Support for Continuing Education in the

Health Professions ……………………………

—Robert Steinbrook, M.D. ……………………………………… 104

Remarks ……………………………………………

—Jordan J. Cohen, M.D. ………………………………………… 127

Discussion Highlights ………………………………………… 132

III. DESIGNING SYSTEMS FOR LIFELONG LEARNING ………………

TO IMPROVE HEALTH …………………………………………… 141

Continuing Health Professional Education Delivery

in the United States ……………………………

—David A. Davis, M.D., and Trina Loofbourrow, B.A. ……… 142

Remarks ……………………………………………

—Pamela Mitchell, Ph.D., M.S., B.S. …………………………… 177

Discussion Highlights ………………………………………… 179

Table of Contents

2

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 2

The Macy Conference format provides ample time for discussion and, after

reading commissioned background papers and hearing remarks prepared

by the authors and several participants, the 36 participants seated around

the table offered countless informed observations, comments, and opinions.

The Discussion Highlights sections at the end of each session group these

comments according to themes that emerged, though many comments might

have been placed in several categories. The papers, remarks, and comments

have been lightly edited for brevity and clarity. On the final day, partici-

pants developed the set of conclusions and recommendations found in the

Executive Summary and, again, beginning on page 219.

3

Learning to Work Together to Improve the

Quality of Healthcare …………………………

—Maryjoan D. Ladden, Ph.D., R.N. …………………………… 182

Remarks ……………………………………………

—Carol Havens, M.D. …………………………………………… 189

Discussion Highlights ………………………………………… 191

IV. REACTION FROM THE TRENCHES ……………………………… 195

Remarks ……………………………………………

—Grant S. Fletcher, M.D., M.P.H. ……………………………… 196

—James A. Clever, M.D. ………………………………………… 199

—Susan W. Wesmiller, M.S., R.N. ……………………………… 200

—Regina Benjamin, M.D., M.B.A. ……………………………… 203

Discussion Highlights ………………………………………… 206

V. MOVING TOWARDS THE FUTURE ………………………………… 209

Continuing Medical Education: Some Important ………

Odds and Ends …………………………………

—David C. Leach, M.D. ………………………………………… 210

Discussion Highlights ………………………………………… 216

Conference Conclusions and Recommendations …………………… 219

Additional References Suggested by Conference Participants ……… 225

Biographical Sketches and Statements of Potential Conflicts of ……

Interest of Conference Participants ……………………………… 230

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 3

Preface

June E. Osborn, M.D.

During my tenure as president of the Macy Foundation, we funded

efforts to improve undergraduate health professional and even

graduate medical education. However, it seemed difficult, if not

impossible, to find a useful entry point on continuing education,

even though it was a massive enterprise that was mandated very

broadly. What is more, I repeatedly bumped up against the fact that

much of the funding for continuing medical education (CME) was

being provided by pharmaceutical company sponsors. Decades

earlier that was true, of course, but not to anywhere near the extent

that had come to be the case. In fact, as I inquired of colleagues

closer to the issue than I was, I got estimates that 60-90 percent of

all CME was supported by industry. Indeed, so pervasive was that

mechanism of support that almost no alternative sources remained.

While there was nothing intrinsically wrong with that state of affairs,

it tended to be festooned by associated phenomena having little to

do with education per se, such as free lunches, gifting of other sorts,

or even more attractive subsidies such as opportunities to qualify for

CME credits by enrolling in courses offered in desirable spots.

4

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 4

5

Clearly there was room for considerable concern about the planning

of offerings for life-long learning, not to mention possible distortion

of objectivity of CME content design and delivery.

I became increasingly troubled as, over time, requirements by state

licensing bodies to accumulate arbitrary hours of CME credit became

virtually universal, and yet they could be satisfied rather randomly,

or at least without any consistency or quality control as to format

and content. The well-established PowerPoint presentation format

had become nearly universal, and there was little evident impetus

or support for other forms of learning, especially at points of care.

All those worrisome trends in CME content, quality, and relevance

to practice were evolving at a time when bench-to-bedside transla-

tional research was being promoted and when biomedical advances

made the need for pertinent life-long learning experiences ever

more urgent and important.

By happy chance, I got into a discussion of these concerns with

Dr. Suzanne Fletcher early in 2006, at a time when I was trying to

formulate plans for the final Macy Conference to be held prior to my

retirement at the end of 2007. When I asked if she — with her long

leadership of a large Harvard CME course — thought that would be

a timely and useful topic for a conference, she endorsed the idea

vigorously. Better yet when I began to plan, the first step — choosing

a chairperson — fell neatly into place. Suzanne’s enthusiasm was

matched by her energy, and she agreed to chair the planning,

convening, and subsequent monograph preparation.

This volume, then, is the product of the resultant Macy Conference,

held in Southhampton, Bermuda from November 28 to December 1,

Osborn

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 5

2007. In preparation for the conference, an excellent and hard-working

planning committee delineated areas of need for newly commissioned

papers, set an agenda for the conference over two-and-one-half

days, and worked diligently to be sure that the professional and

experiential range of the participants invited to contribute to the

deliberations would provide as many pertinent voices as possible

to assure a rich discussion. Given that all the health professions are

facing similar or analogous problems to those of medicine, efforts

were made to include nursing, in particular, and other professions’

experience where possible. The resulting conference was remark-

ably stimulating and led to a broad consensus, expressed in the

conclusions and recommendations presented in this monograph.

As Dr. Fletcher says eloquently in her Introduction, the resultant

exploration of the facts, deficiencies, needs, and challenges for

continuing education of health professionals is certainly timely. I

hope it serves to move the health professions forward in their pur-

suit of optimal ways to provide and require continuing education

throughout the professional lifetimes of their members.

President Emerita, Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation

6

Preface

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/12/08 11:07 AM Page 6

7

Introduction

Suzanne Fletcher, M.D., M.Sc.

Harvard Medical School

Chair

In November, 1908 the Board of Trustees of the Carnegie Foundation

authorized what many consider the seminal study of medical

education in this country. Two years later Abraham Flexner published

his report on medical education in the United States and Canada.

1

The report was so influential that most physicians in the United

States continue to be educated according to Flexner’s precepts.

One hundred years later, the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation convened

a Conference on Continuing Education in the Health Professions.

Our mandate was to examine continuing education in multiple

health professions, not undergraduate medical education. So why

bring up Flexner, who wrote his report many years even before the

birth of the Macy Foundation? When I perused Flexner’s report in

preparation for our gathering, I was struck that, even now, many

aspects of that nearly 100-year-old document remain remarkably

relevant to our deliberations at this conference.

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 7

First, why is education in the health professions so important anyway?

The Carnegie Foundation undertook their study with two major

interests in mind, or as President Pritchett put it, “first, the youths

who are to study medicine and to become the future practitioners,

and secondly, the general public, which is to live and die under

their ministrations.”

2

The planning committee for this conference

came to a remarkably similar conclusion. At our very first meeting,

Marc Nivet asked about the view from the trenches, and this question

led to an important session in our conference. Later, when we were

deep into thinking about the complicated educational approaches,

financing, and structures involved in continuing education, June

Osborn, who has stressed the public throughout her tenure as

President at Macy, and Jordan Cohen brought it all into focus by

reminding us that what makes these deliberations truly important

is the need to improve the quality of healthcare. This broader social

perspective separates education in the health professions from

many other worthy educational endeavors.

The second reason why Flexner’s report remains relevant is that he

addressed the type and mode of education. He visited every one

of the 150 medical schools in existence at that time to observe

precisely what subjects were taught and how they were taught. He

concluded that too often laboratory science and bedside teaching

were neglected in favor of didactic lectures. He summed up his

argument for the need for hands-on learning by quoting an earlier

article by Cabot and Locke:

Learning medicine is not fundamentally different from learning

anything else. If one had one hundred hours in which to learn

to ride a horse or to speak in public, one might profitably spend

perhaps an hour (in divided doses) in being told how to do it,

four hours in watching a teacher do it, and the remaining ninety-

five hours in practice, at first with close supervision, later under

general oversight.

3

Today, how best to conduct continuing education so as to positively

affect the health of patients and the public remains a challenge.

That we have a ways to go is clear from many studies demonstrating

large differences — a “chasm” according to the IOM report

4

—

between what should be done and what is done in practice. Don

Introduction

8

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 8

Fletcher

9

Moore presented a wonderful summary of what we know today

about how clinicians learn. He pointed out that most formal continuing

education programs continue to be made up of didactic lectures

and very few — Don estimates 5 percent — on assessing competence

and performance. What Flexner (and Cabot and Locke) said 100

years ago still applies.

Medical specialty boards are beginning to address this problem

with the requirement of maintenance of certification programs.

As Dan Duffy described in his presentation, these programs require

clinicians to review the care they actually deliver in their own prac-

tices, compare the results with standards of excellence, and create

a plan for improvement. This approach goes back to the 95-hour

rule Flexner advocated so long ago.

Perhaps the most important issue in continuing education today is

its financing. Robert Steinbrook pointed out that commercial support

for accredited continuing medical education in the United States

has quadrupled in less than a decade, and last year it reached a total

of $1.5 billion—accounting for about 60 percent of the income for

all of the accredited continuing medical education programs in the

United States. No wonder we see a rising concern that commercial

interests may be distorting the education of practicing clinicians. The

U.S. Senate Finance Committee summed it up this way: “It seems

unlikely that [a] sophisticated industry would spend such large sums

on an enterprise but for the expectation that the expenditures will

be recouped by increased sales.”

5

The Senate Committee called for

better oversight to ensure that continuing education programs are

independent of drug company interests.

Flexner wrote his report 100 years ago, when very few effective

drugs existed, when Osler advocated little more than morphine,

nitroglycerin, iron, and quinine. How could Flexner have any rele-

vance to this vexing modern problem? I think he does. Flexner often

used the word “commercial” when describing the problems of the

worst medical schools he visited. He pointed out that laboratory

and patient-based education was expensive while didactic lectures

were cheap, and so the schools that survived and profited only from

fees tended to emphasize the latter. He challenged the fundamental

assumption that medical education should be a business. He advo-

cated the need for standards that, if adopted, clearly would adversely

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 9

affect the financial interests of some.

Today, it is increasingly clear that commercial financing has infiltrated

the very fabric of continuing education. Last year JAMA published a

paper, coauthored by David Blumenthal and Jordan Cohen, calling

for academic medical centers to take the lead in eliminating conflicts

of interest between physicians and industry. The authors proposed

that manufacturers should not be permitted to provide support for

any ACCME-accredited continuing education program and, further,

that faculty should not serve on speakers’ bureaus sponsored by

drug companies.

6

Results from a recent survey of medical school department chairs,

published in JAMA, show just how difficult it will be to move this

call from proposal to policy; 60 percent of the department chairs had

some form of financial relationship with industry, as did two thirds

of their departments

.

7

Most chairs perceived no ill effects from these

relationships, and most viewed them as helpful to the educational

process. Our conference dealt squarely with this conundrum.

With regard to organizations that teach, Flexner recommended that

medical education be linked closely with universities. He was con-

vinced that such linkage would provide higher standards, better

teachers, and more resources for students. He also recommended that

teaching hospitals have close links to medical schools. Fundamentally,

he was suggesting that organizational aspects of education should

be set up to achieve the best possible education.

What about the situation today? Dave Davis has provided us with an

overview of the organizations involved in and accrediting continuing

education in medicine, pharmacy, and nursing; the landscape is

crowded, with many different types of organizations involved— far

more than for undergraduate and graduate education. Is this the best

way? We devoted a session of our conference to this topic.

One area barely mentioned by Flexner is interprofessional collabo-

ration, but today high-quality healthcare demands communication,

collaboration, and teamwork among heath professionals. Several IOM

reports on quality of healthcare in this country have stressed team-

work and systems changes. Maryjoan Ladden argued that continuing

education of various health professionals together promotes collabo-

10

Introduction

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 10

ration, decreases adverse health effects, and improves healthcare.

I found no comment about continuing education in Flexner’s report.

However, one of the giants of that age, William Osler, was acutely

aware of its importance. He thought physicians had an obligation to

keep learning about medicine from others, both through the literature

and through subjecting their practices to the scrutiny of colleagues.

He loved medical libraries and amassed a private library of approxi-

mately 8000 books. He summed up his feelings this way: “It is

astonishing with how little reading a doctor can practice medicine,

but it is not astonishing how badly he may do it

.

”

8

One hundred

years later, we still have a ways to go.

If Flexner had attended this conference, perhaps the most fascinat-

ing part for him would have been the discussion about the Internet

and its effect on the ability of doctors and nurses to keep up with

new information. Denise Basow and Don Lindberg both offered

presentations describing the ways in which this wonderful new

technology provides, really for the first time, just-in-time learning

for all of us in the health professions, and, as Don pointed out, for

our patients.

Flexner made major recommendations for change. This conference

also has led to major recommendations, although we spent two and

a half days together as opposed to Flexner’s two years’ effort. Also,

David Leach reminded us about the efforts of other groups. What

can one more report from a Macy Conference contribute?

I think there are at least two possibilities. First, our perspective cuts

across health professions. Second, the participants in this conference

were invited as leaders in the medical, nursing, and education

professions, not as representatives of organizations involved in

continuing education. As such, we had the opportunity to consider

continuing education of the healthcare professions as it contributes

to our professions and to society at large. By adopting this approach,

our goal was that the description of a profession written many years

ago in a legal opinion, and echoing Justice Brandeis’ famous quote,

continues to apply today:

A profession is not a business. It is distinguished by the require-

ments of extensive formal training and learning, admission to

11

Fletcher

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 11

12

Introduction

practice by qualifying licensure, a code of ethics imposing stan-

dards qualitatively and extensively beyond those that prevail or

are tolerated in the marketplace, a system for discipline of its

members for violation of the code of ethics, a duty to subordi-

nate financial reward to social responsibility, and notably, an

obligation on its members, even in non-professional matters, to

conduct themselves as members of a learned, disciplined, and

honorable occupation.

9

REFERENCES

1. Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. A Report to the

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New York: The Carnegie

Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

2. Pritchett HS. Introduction. In Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and

Canada. A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New

York: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910. p. vi–xvii.

3. Cabot RC, Locke EA. The organization of a department of clinical medicine. Boston

Med Surg J. 1905;153:461–465.

4. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America. Crossing the

Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National

Academy Press; 2001.

5. Committee Staff Report to the Chairman and Ranking Member. Use of Educational

Grants by Pharmaceutical Manufacturers. Washington DC: United State Senate

Committee on Finance; April 2007.

6. Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, et al. Health industry practices that create con-

flicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA.

2006;295:429–433.

7. Campbell EG, Weissman JS, Ehringhaus S, et al. Institutional academic-industry rela-

tionships. JAMA. 2007;298:1779–1786.

8. Osler W. Books and men. In: Osler W. Aequanimatas and Other Addresses.

Philadelphia: P. Blakeson’s Sons and Co; 1905. p. 22.

9. New York Court of Appeals Statement on Matter of Freeman, 311 N. E. 2d 480(1974).

Accessible at www.wsba.org/atj/committees/jurisprudence/jurisethics.htm (Access

date: February 15, 2008).

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 12

Chairman’s Summary

of the Conference

Continuing education (CE) of health professionals is essential to

the health of all Americans. With accelerating advances in health

information and technology, physicians, nurses, and other health

professionals must maintain and improve their knowledge and skills

throughout their careers in order to provide safe, effective, and high

quality healthcare for their patients.

Yet continuing education in the health professions is in disarray.

Over the past decade, both professional and lay reports have

identified multiple problems. CE, as currently practiced, does not

focus adequately on improving clinician performance and patient

health. There is too much emphasis on lectures and too little empha-

sis on helping health professionals enhance their competence and

performance in their daily practice. With Internet technology, health

professionals can find answers to clinical questions even as they

care for patients, but CE does not encourage its use or emphasize

its importance. And, while studies show that inter-professional

collaboration, teamwork, and improved systems are key to high

quality care, accrediting organizations have not found ways to

promote teamwork or align CE with efforts to improve the quality

of health systems.

Another significant problem is the growing link between continuing

education and commercial interests. In 2006, the total income for

accredited CE activities in medicine was $2.4 billion. Commercial

support from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers

accounted for more than 60 percent, about $1.45 billion, of the total.

Over the past two years, the Senate Finance Committee has investi-

gated pharmaceutical company support for continuing education

13

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 13

in medicine. Despite efforts to control improper influences, the

committee concluded that the organizations providing continuing

education could still accommodate commercial interests of sponsors

and sponsors could still target their funding for educational

programs likely to support sales of their products.

To address concerns about CE, the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation

convened a conference on “Continuing Education in the Health

Professions.” Suzanne W. Fletcher, M.D., M.Sc., Professor of

Ambulatory Care and Prevention, Emeritus, at Harvard Medical

School, served as chair. The two-and-one-half-day conference,

which was held in Bermuda in November of 2007, included 36

leaders in medicine, nursing, and education. Commissioned back-

ground papers covered a range of CE-related topics, including a

review of how physicians and other health professionals learn, the

role of information technology, financing, and certification.

Although much of the conference discussion was relevant to the

continuing education of all health professionals, participants focused

on accredited CE for medicine and nursing. They acknowledged

that much professional learning takes place informally and outside

accredited formats.

Conference themes were inter-related, for the methods used for

continuing education are influenced both by the means of financial

support and by mechanisms for accreditation. Unfortunately,

participants found, current systems of CE do not meet the needs

of health professionals as well as they should:

— Too much CE relies on a lecture format and counts hours of

learning rather than improved knowledge, competence, and

performance.

— Too little attention is given to helping individual clinicians examine

and improve their own practices.

— Insufficient emphasis is placed on individual learning driven by

the need to answer the questions that arise during patient care.

— CE does not promote inter-professional collaboration, feedback

from colleagues and patients, teamwork, or efforts to improve

systems of care, activities that are key to improved performance

14

Chairman’s Summary

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 14

by health professionals.

— CE does not make adequate or creative use of Internet technology,

which can help clinicians examine their own practice patterns,

bring medical information to them during patient care, and aid

them in learning new skills.

— There is too little high-quality scientific study of CE.

Participants warned that the health professions, especially medicine,

threaten the ethical underpinnings of professionalism by participat-

ing in a multi-billion dollar CE enterprise so heavily financed by

commercial interests. This arrangement, which evolved over the

years, distorts continuing education. It places physicians and nurses

who teach CE activities in the untenable position of being paid,

directly or indirectly, by the manufacturers of healthcare products

about which they teach. At the same time, commercial support of

CE places learners in an obligatory position because they are often

given free meals and small gifts. Independent judgment of how

best to care for patients is compromised. Bias, either by appearance

or reality, has become woven into the very fabric of continuing

education. The professions, themselves, must right this wrong.

In a free-market system, commercial entities, such as drug and

device manufacturers, have a clear responsibility to shareholders to

gain market advantage and generate a profit, while health profes-

sionals have a moral responsibility to provide safe, high quality

care for their patients, based on valid scientific findings. The two

responsibilities are fundamentally incompatible. Even if bias could

be avoided, the potential, and the perception, are ever-present.

Companies with billions of dollars at stake cannot be expected to

be neutral or objective when assessing the benefits, harms, and

cost-effectiveness of their products, for they are in the legitimate

business of gaining market advantage and want clinicians to use

and prescribe their products.

Yet, an objective and neutral assessment of clinical management

options is precisely what is needed in continuing education.

Participants emphasized that, regardless of the financial impact on

for-profit companies, patient care must be based on scientific evidence

and commercial interests should not determine the topics or content

Fletcher

15

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 15

of CE. Because of these underlying ethical issues, participants

concluded that the commercial entities that manufacture and sell

healthcare products should not provide financial support for the

continuing education of health professionals.

Participants acknowledged that many major advances in health-

care, especially in the development of new drugs and devices,

have come from careful collaboration between medical and

commercial investigators. Too, corporations have made valuable

donations to academic health centers to support professorships,

scholarships, programs, and buildings, all of which contribute to

the public good.

Despite recent changes in CE accreditation to reduce commercial

influence, the problem persists and organizations with little profes-

sional expertise in healthcare, and supported almost entirely by

commercial interests, provide accredited continuing education. At

the same time, accrediting groups require all organizations providing

CE to go through laborious, bureaucratic procedures to document

that no inappropriate influence has occurred.

Participants pinpointed another serious failure with current accredi-

tation mechanisms. At a time when inter-professional collaboration,

teamwork, and improvement of systems are key to high quality

healthcare, accrediting organizations for the various health profes-

sions still work in silos. Rather than promoting inter-professional

collaboration and education, regulations and procedures for

accreditation make inter-professional collaboration difficult. And,

while systems of care have a major impact on the quality of health-

care delivered by clinicians, accrediting organizations have been

slow to align their CE activities with quality improvement efforts

by systems of care.

Participants identified a set of principles they believe should underlie

and guide continuing education of the health professions:

— Integrate continuing education into daily clinical practice.

— Base continuing education on the strongest available evidence

for practice.

16

Chairman’s Summary

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 16

— Minimize, to the greatest extent possible, both the reality and the

appearance of bias.

— Emphasize flexibility and easy accessibility for clinicians.

— Stress innovation and evaluation of new educational methods.

— Address needs of clinicians across a wide spectrum, from

specialists in academic health centers to rural solo practitioners.

— Support inter-professional collaboration.

— Align continuing education efforts with quality improvement

initiatives at the level of health systems.

After two and a half days of discussion, participants agreed to the

following conclusions and recommendations:

CONCLUSIONS

Continuing Education and the Public

The quality of patient care is profoundly affected by the performance

of individual health professionals.

The fundamental purposes of continuing health professional

education (CE) are:

— To improve the quality of patient care by promoting improved

clinical knowledge, skills and attitudes, and by enhancing

practitioner performance.

— To assure the continued competency of clinicians and the

effectiveness and safety of patient care.

— To provide accountability to the public.

CE fulfills a critically important, indeed essential, public purpose.

Given the accelerating pace of change in clinical information and

technology, CE has never been more important.

Fletcher

17

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 17

18

Responsibilities of Individual Professionals, Professional

Teams, and Health Systems

Maintaining professional competence is a core responsibility of

each health professional, regardless of discipline, specialty, or type

of practice.

The individual clinician has been the principal unit of accountability

for performance in the healthcare delivery system. Given that the

performance of health systems also profoundly affects patient care,

CE fails to take into account systems of care.

Effective patient care increasingly depends on well-functioning

teams of healthcare professionals. Therefore, CE must address the

special learning needs of collaborating teams.

Quality improvement efforts and CE activities overlap and ideally

are mutually reinforcing.

CE Methods

Traditional lecture-based CE has proven to be largely ineffective in

changing health professional performance and in improving patient

care. Lecture formats are employed excessively relative to their

demonstrated value.

Professional conferences play an important role in CE by promoting

socialization and collegiality among health professionals. Health

professionals have the responsibility to help one another practice

the best possible care. Meeting together provides opportunities for

cross-disciplinary and cross-generational learning and teaching.

Practice-based learning and improvement is a promising CE

approach for improving the quality of patient care. Maintenance

of certification programs (in which clinicians review the care they

actually deliver in their own practices, compare the results with

standards of excellence, and create a plan for improvement) and

maintenance of licensure programs are moving CE in this direction.

Currently, most CE faculty are insufficiently prepared to teach

practice-based learning.

Information technology is essential for practice-based learning by:

Chairman’s Summary

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 18

— Providing access to information and answers to questions at the

time and place of clinical decision-making (point-of-care learning).

— Providing a database of clinician performance at the individual

and/or group practice level, which can be compared to best

practices and used to make plans for improvement.

— Providing automated reminder systems.

Interactive scenarios and simulations are promising approaches to

CE, particularly for skills development, whether the skill is a highly

technical procedure, history taking, or a physical examination

technique.

Insufficient research is currently directed at improving and evaluating

CE. There is no national entity dedicated to advancing the science of

CE as there is for biomedical and clinical research.

Financing CE

The majority of financial support for accredited CME, and increas-

ingly for CNE, derives directly or indirectly from commercial entities.

Pharmaceutical and medical device companies and healthcare pro-

fessionals have inherently conflicting interests in CE. Commercial

entities have a legitimate obligation to enhance shareholder value

by promoting sales of their products, whereas healthcare profession-

als have a moral obligation to improve patient/public health without

concern for the sale of products.

Commercial support for CE:

— Risks distorting the educational content and invites bias.

— Raises concerns about the vows of health professionals to place

patient interest uppermost.

— Endangers professional commitment to evidence-based decision

making.

— Validates and reinforces an entitlement mindset among health

professionals that CE should be paid for by others.

Fletcher

19

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 19

20

— Impedes the adoption of more effective modes of learning.

No amount of strengthening of the “firewall” between commercial

entities and the content and processes of CE can eliminate the

potential for bias.

Academic health centers and other healthcare delivery systems are

not sufficiently attentive, either to their roles in planning, providing,

and assessing CE or to their responsibilities in managing their own

conflicts of interest and those of individual faculty and administrators

when paid by commercial interests for CE teaching.

Accrediting CE

Current accreditation mechanisms for CE are unnecessarily complex

yet insufficiently rigorous. Compared to earlier, formal stages of

health professions education, the CE enterprise is fragmented, poorly

regulated, and uncoordinated; as a result, CE is highly variable in

quality and poorly aligned with efforts to improve quality and

enhance health outcomes.

With the increasing need for inter-professional collaboration,

accrediting bodies of the various health professionals need closer

working relationships.

RECOMMENDATIONS

CE Methods

The CE enterprise should shift as rapidly as possible from excessive

reliance on presentation/lecture-based formats to an emphasis on

practice-based learning.

New metrics are needed:

— To assess the quality of CE. These metrics should be based

on assessment of process improvement and enhanced patient

outcomes.

— To identify high-performing healthcare organizations. The

possibility of awarding CE credit to individual health professionals

who practice in such organizations should be explored.

Chairman’s Summary

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 20

— To automate credit procedures for point-of-care learning.

Federal and state policymakers should provide financial support

for the further development of information technology tools that

facilitate practice-based learning and should strongly encourage all

clinicians to use these tools.

The responsibility for lifelong learning should be emphasized

throughout the early, formal stages of education in all health

professions. Students should be taught the attitudes and skills to

accomplish CE throughout their professional lifetimes.

A national inter-professional CE Institute should be created to

advance the science of CE. The Institute should:

— Promote the discovery and dissemination of more effective

methods of educating health professionals over their profession-

al lifetimes and foster the most effective and efficient ways to

improve knowledge, skills, attitudes, practice, and teamwork.

— Be independent and composed of individuals from the various

health professions.

— Develop and run a research enterprise that encourages increased

and improved scientific study of CE.

— Promote and fund evaluation of policies and standards for CE.

— Identify gaps in the content and processes of CE activities.

— Develop mechanisms needed to assess and fund research

applications from health professional groups and individuals.

— Stimulate development and evaluation of new approaches to

both intra- and inter-professional CE, and determine how best

to disseminate those found to be effective and efficient.

— Direct attention to the wide diversity and scope of practices

with special CE needs, ranging from highly technical specialties

on the one hand to solo and small group practices in remote

locations, on the other.

Fletcher

21

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 21

Chairman’s Summary

22

— Acquire financial resources to support its work and provide

funding for research. Possible funding sources include the

Federal government, foundations, professional groups, and

corporations.

A concerted effort is needed to make the concept of a Continuing

Education Institute a reality. To achieve this, The Institute of Medicine

should convene a group to bring together interested parties to propose

detailed steps for developing a Continuing Education Institute.

CE Financing

Accredited organizations that provide CE should not accept any

commercial support from pharmaceutical or medical device compa-

nies, whether such support is provided directly or indirectly through

subsidiary agencies. Because many professional organizations and

institutions have become heavily dependent on commercial support

for current operations, an abrupt cessation of all such support would

impose unacceptable hardship. A five-year “phase out” period

should be allowed to meet this recommendation.

The financial resources to support CE should derive entirely from

individual health professionals, their employers (including academic

health centers, healthcare organizations, and group practices), and/or

non-commercial sources.

Faculty of academic health centers should not serve on speakers’

bureaus or as paid spokespersons for pharmaceutical or device

manufacturers. They should be prohibited from publishing articles,

reviews, and editorials that have been ghostwritten by industry

employees.

CE Accreditation and Providers

Organizations authorized to provide CE should be limited to profes-

sional schools with programs accredited by national bodies, not-for-

profit professional societies, healthcare organizations accredited by

the Joint Commission, multi-disciplinary practice groups, point-of-care

resources, and print and electronic professional journals.

Existing accrediting organizations for continuing education for

medicine (the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 22

Fletcher

23

Education) and nursing (the American Nurses Credentialing Center)

should meet and within two years develop a vision and plan for a

single accreditation organization for both nursing and medicine.

The new organization should incorporate the guiding principles for

CE and the recommendations laid out in this report where relevant.

The American Academy of Nursing and the Association of American

Medical Colleges should convene the two accrediting bodies for

this purpose.

Academic health centers should examine their missions to determine

how to strengthen their commitment to CE. They should help their

faculty gain expertise in teaching practice-based learning and incor-

porate information technology, simulations, and interactive

scenarios into their CE activities.

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 23

Suzanne W. Fletcher, M.D., M.Sc.*

Harvard Medical School

Chair

________________________________

Barbara F. Atkinson, M.D.

University of Kansas Medical Center

Denise Basow, M.D.*

UpToDate

Waltham, MA

Regina Benjamin, M.D., M.B.A.

Bayou Clinic, Inc.

Bayou La Batre, AL

David Blumenthal, M.D., M.P.P.

MGH/Partners Healthcare System

James A. Clever, M.D.

Marin County, CA

Jordan J. Cohen, M.D.*

Association of American Medical Colleges

Ellen M. Cosgrove, M.D.*

University of New Mexico School of

Medicine

Linda Cronenwett, Ph.D., R.N.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

David A. Davis, M.D.

Association of American Medical Colleges

Catherine D. DeAngelis, M.D., M.P.H.

JAMA and Archives

John Hopkins University

Lyn DeSilets, Ed.D., R.N.-B.C.

Villanova University

F. Daniel Duffy, M.D.*

American Board of Internal Medicine

Harvey Fineberg, M.D., Ph.D.

Institute of Medicine

Grant S. Fletcher, M.D., M.P.H.

University of Washington School

of Medicine

Melvin I. Freeman, M.D.

Virginia Mason Medical Center

Seattle, WA

Michael Green, M.D., M.Sc.

Yale University School of Medicine

Carol Havens, M.D.

Kaiser Permanente Medical Center

Sacramento, CA

Paul C. Hébert, M.D., M.H.Sc.

Canadian Medical Association Journal

Maryjoan D. Ladden, Ph.D., R.N.*

Harvard Medical School

Participants

24

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 24

David Leach, M.D.*

Accreditation Council for Graduate

Medical Education

Donald A. B. Lindberg, M.D.*

National Library of Medicine

Phil Manning, M.D.

Keck School of Medicine of the

University of Southern California

Paul Mazmanian, Ph.D.

Virginia Commonwealth University

Pamela Mitchell, Ph.D., M.S., B.S.

University of Washington

Donald E. Moore Jr., Ph.D.

Vanderbilt School of Medicine

Ajit K. Sachdeva, M.D.

American College of Surgeons

Marla E. Salmon, Sc.D., R.N.

Emory University

David C. Slawson, M.D.

University of Virginia

Robert Steinbrook, M.D.

New England Journal of Medicine

William Tierney, M.D.

Indiana University School of Medicine

Thomas R. Viggiano, M.D., M.Ed.

Mayo Clinic

Susan Wesmiller, M.S., R.N.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Michael Wilkes, M.D.

University of California, Davis

Patricia S. Yoder-Wise, R.N., Ed.D.

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center

MACY FOUNDATION

June E. Osborn, M.D.*

Marc A. Nivet, Ed.D.

Nicholas R. Romano, M.A.

Mary Hager, M.A.

*

Planning Commitee

Macy Conference participants are invited for their individual perspectives

and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization.

25

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 25

26

Conference Images

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 26

27

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 27

28

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 28

I.

Approaches to

Knowledge Development

—

What Works and

What Does Not

29

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 29

30

How Physicians Learn and How to

Design Learning Experiences for Them:

An Approach Based on an Interpretive

Review of Evidence

Donald E. Moore, Jr., Ph.D.

Vanderbilt School of Medicine

Researchers from multiple studies over the past several years have

reported that there are distressing gaps between the healthcare services

that patients receive and those that they could be receiving.

1,2

These

studies show that many patients do not receive the best possible

care, receive suboptimal care, or are victims of errors, despite the

fact that approaches to care are improving and demonstrating

enhanced outcomes. A variety of approaches have been suggested

to address this gap.

3

Continuing medical education (CME) has been

a longstanding suggestion. For many years, however, people have

expressed concerns about the effectiveness of CME. As a result,

confidence in the ability of CME to address the identified gaps in

healthcare delivery was not high. But significant work over the past

20 years has demonstrated the effectiveness of CME, if it is planned

and implemented according to approaches that have been shown

to work.

4–6

This interpretive essay reviews the evidence that describes how

physicians learn and proposes six principles from that evidence and

research from other fields that can be used to plan formal educational

activities designed to facilitate physician learning. Next, the essay

proposes an instructional design approach for designing effective

formal CME activities. Finally, the essay briefly discusses assessment

of formal CME activities. See Appendix A for a brief review of the

evidence on how nurses and pharmacists learn.

How Do Physicians Learn?

At any given time, physicians are engaged simultaneously in several

different kinds of learning. Systematic reading, self-directed improve-

ment at work, participation in formal CME courses, and consultation

with colleagues are woven into the basic fiber of their professional

lives to create an approach to learning that is unique to each individual

physician. Studies on physician learning have revealed that the

learning process consists of several stages. In general, these stages

begin with a physician learner becoming aware of a problem or

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 30

R

ecognizing

a

n Opportunity

for Learning

S

earching for

R

esources

for Learning

E

ngaging

i

n Learning

T

rying Out

W

hat Was

Learned

I

ncorporating

W

hat Was

Learned

Priming

Reflecting-in-action

Reflecting-on-

action

Awareness

Priming

Pre-awareness

Awareness

Scanning

Awareness

Felt need

Felt need

Articulate a

problem

Awareness

Pre-contemplation

Contemplation

Experiencing

Reflecting

Focusing

Decision to pursue

information

Actively seeking

a solution

Decision-making

Preparing to

make a change

Follow-up

Agreement

Evaluating

Obtain

knowledge about

an innovation

Search for

solutions

Information

seeking

Interest

Preparation

Conceptualization

Planning

Focusing

Develop

learning project

Making the

change

Follow-up

Learning

Obtain

knowledge about

an innovation

Preparation

Planning

Follow-up

Solidifying the

change

Follow-up

confirmation

Adoption

Gaining

experience

Favorable opinion

about the

innovation

Decision to adopt

or reject

Choice

Evaluation

Trial test

Action

Problem

resolution

Solidifying the

change

Adherence

Gaining

experience

Implementation

Confirmation

Application

of solution

Adoption

Integration

Maintenance

G

eertsma

et al

1

982

1

5

Schon

1983

16

Means

1984

17

Putnam,

Campbell

1989

1

8

Garcia,

Newsom

1996

19

Pathman

et al

1996

20

Slotnick

1999

21, 22

Rogers

1962

23, 24

Havelock

et al

1969

25, 26

Havelock

et al

1973

25, 26

Prochaska

1983

27-29

Kolb

1984

30

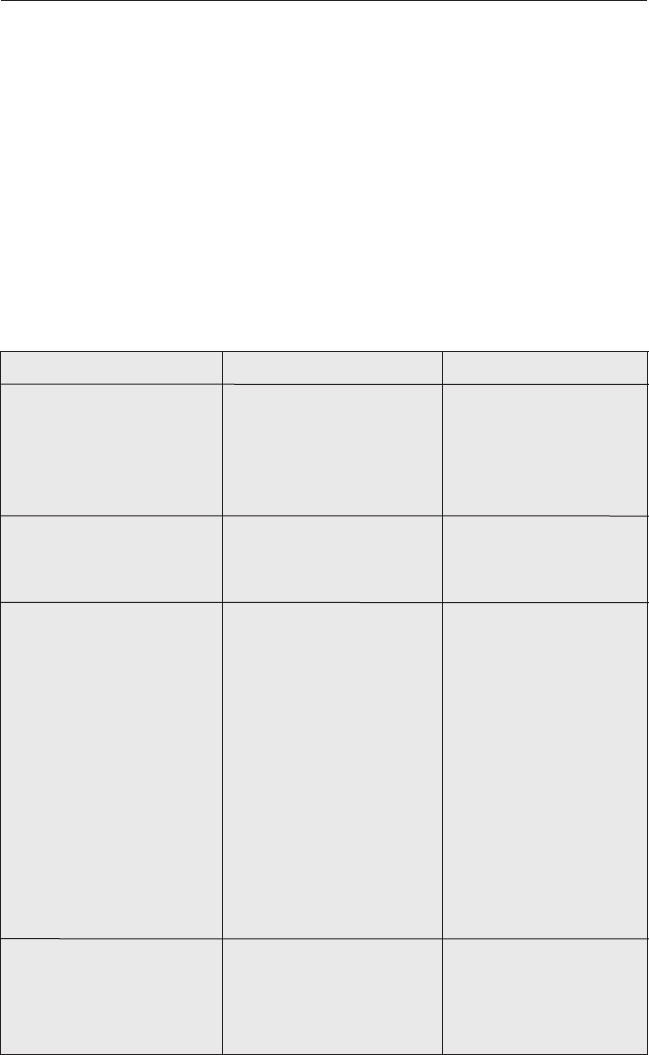

Table 1. Stages of Learning

S

tudies on Physician Learning

Studies on How People Learn

Moore

31

challenge and end when all stages are completed, with that physician

learner comfortably and confidently applying newly learned knowl-

edge and/or skills (Table 1).

Stage theories are used commonly in the social and behavioral

sciences.

7

A stage theory describes a social or behavioral process

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 31

in terms of the collection of activities that an individual must pass

through in order to successfully complete that process. Descriptions

of learning as a process that includes several stages have been in

the educational literature at least since the early 1950s.

8

Tough,

9–11

Knowles,

12

and Knox

13

have reported stage learning projects of

adults who planned and directed the projects, consisting of multiple

stages, for themselves.

There is a danger of oversimplification when describing a complicated

process like learning as a straight line that “flows” from stage to stage.

In fact, the process of learning is extraordinarily complex, and it is

made even more complex because it is embedded in a social context.

It is more dynamic, with many interactions among the stages and

within the stages. The system dynamics model described by Hirsch

and his colleagues

14

is probably a more accurate way to depict the

process. For the purposes of this monograph, however, we use the

more static approach because the studies we are reviewing were

reported in that way, and while possibly oversimplified, this

approach helps us understand the process at a very macro level.

The findings of seven studies that examined physician learning and

five studies that examined how people learn are summarized in Table1.

These studies revealed that learning begins with an individual becoming

aware of a problem or challenge and ends when all stages are com-

pleted, with that learner comfortably and confidently applying newly

learned knowledge and/or skills. We propose a five-stage model

that synthesizes the stages identified in the studies reviewed here. The

five stages are reflected as the headings of Table 1: 1) recognizing

an opportunity for learning; 2) searching for resources for learning;

3) engaging in learning to address an opportunity for improvement;

4) trying out what was learned; and 5) incorporating what was learned.

It is a precarious endeavor to synthesize the results of studies con-

ducted by others in an attempt to create a working theory. There

are dangers of over-interpreting some studies and under-interpreting

others. There is also a danger of making assumptions that the original

researchers did not intend. In addition, each of the models presented

has its own characteristics and features, which may be overemphasized

or underemphasized in the synthesis. Furthermore, the stages proposed

may contain part of a stage from one study and two stages from

another study. The following paragraphs describe these stages in

more detail as they relate to physician learning.

32

How Physicians Learn and How to Design Learning Experiences for Them

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 32

Stage 1: Recognizing an opportunity for learning

This is the initial stage of the process of physician learning. In this

stage, a physician begins to sense that there may be something in

his or her practice that is “not right” and may begin to consider

learning as a way to address it. The term “scanning” describes the

sometimes conscious, sometimes subconscious examination of a

physician’s practice and his or her professional environment that

results in a state of dissatisfaction with some aspect of the practice

or practice performance. Scanning may be passive, when a physician

reacts to surprises in practice or “feels” that something may not be

right, or it may be more active, when the physician is actively engaged

in examining areas that he or she has identified as opportunities for

improvement. The terms “reflecting-in-action” and “reflecting-on-

action” describe what a physician does when he or she becomes

“aware” that something is not right with the management of a patient

or group of patients, or if there might be a better way to manage a

patient. The product of reflection is an ongoing “articulation” of a

problem that describes the feeling that something is not right as a

difference between “what should be” and “what is”— what psychol-

ogists call “cognitive dissonance.”

31

For physicians in practice, “what

is” and “what should be” can be described in terms of performance

in practice or patient outcomes. Dissonance is associated with

discomfort that causes action to search for a solution to reduce the

discomfort. In a physician, cognitive dissonance will create discomfort,

which, in turn, will lead the physician to search for knowledge that will

make it possible to reduce the discrepancy and the discomfort.

17,32,33

Another way to describe what happens during this stage is to say

that a “teachable moment” emerges. A teachable moment is defined

as the time when a learner’s psychological readiness for learning is

highest.

34

The strength and persistence of the teachable moment will

determine whether a physician will move to the second stage.

What causes a physician to move from recognizing that there is an

opportunity for learning to starting the process to pursue learning?

The strength and persistence of cognitive dissonance, or the teachable

moment, is important, but there are a variety of other issues and

considerations that affect the decision to pursue learning.

35

In the

general adult education literature, Cross

36

suggested that an indi-

vidual is more likely to participate in an educational activity if he or

she 1) possesses positive attitudes about education; 2) considers an

educational activity relevant to his or her educational need; 3) sees

33

Moore

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 33

more opportunities than barriers to participate; and 4) expects to be

successful in learning what he or she needs to learn to address the

educational need (cognitive dissonance) that initiated the search for

a learning opportunity. In the medical literature, Gorman suggests

that physicians will pursue learning if they believe that there is

something to be learned that might resolve the discrepancy at hand,

but they are not inclined to seek answers when they do not believe

that useful information exists.

37

Fox and his colleagues reported that

if a physician perceives learning and the results of learning to be

rational, relatively easy to achieve, and in the best interest of his or

her patients, the physician would be more likely to pursue learning.

If learning is coerced, however, by regulation or administrative

requirements, a physician’s participation would likely be minimal

and grudging. Moore and colleagues saw the decision to participate

in formal CME as part of information-seeking efforts and described

a complex transactional process in which the costs and benefits of

participation were compared at several levels.

38

During this stage, questions may emerge for physicians like “Am I

treating patients (in this disease area) correctly?” “How are my

patients (in this disease area) doing?” “What are the acceptable

standards of care (in this disease area)?” “Is there anything “new”

in this disease area?” And, “What’s important in all this information

that I am hearing about this disease area?”

39

Stage 2: Searching for resources for learning

Practicing physicians seek to address problems they identify for

themselves by starting a search for resources for learning, framed

by these problems stated as questions, articulated at varying levels

of clarity. A question could focus on any number of the components

of patient management: pre-diagnostic evaluation, diagnosis, treat-

ment, or follow-up. A physician seeking information in any of these

areas might be concerned about declarative information (knowledge

base) but is more likely concerned about procedural information

(knowledge about how to use the knowledge base). In addition, a

physician seeking information may be seeking that information as

new knowledge to update his or her current knowledge or to rein-

force current knowledge.

40

During this stage, a physician prepares to make a change to address

the problem he or she has articulated by trying to understand it

34

How Physicians Learn and How to Design Learning Experiences for Them

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 34

and estimating what would have to be learned to address it. The

physician becomes aware of alternative approaches to address the

identified problem, decides which approach to use, and selects

resources to learn about that approach.

A physician begins to develop an image of the change in behavior

that is necessary to address the problem identified during stage 1

and how learning will help accomplish that change.

41

Slotnick found

that during this stage, a physician evaluates the problem or question

to determine whether pursuing learning will be beneficial. Slotnick

suggests that a physician determines the benefits by asking the fol-

lowing questions:

— Does the problem likely have a solution?

— Are resources available to learn the solution to the problem?

— Will learning the solution change my practice in

desirable ways?

If a physician responds to these questions with positive answers, the

next step will be to determine whether she needs to learn something

to make a change. With the image of change in mind,

41

the physi-

cian will determine the extent to which he or she is able to make

the change without learning (her capabilities are adequate) or the

extent to which she will have to pursue learning (she feels that her

capabilities are not adequate). A physician at this stage will assess

her capabilities in a number of ways, including personal reflection,

feedback, and interaction with colleagues, as well as personal,

community, and professional expectations.

42

In addition, a physician

may assess her capabilities while engaged in CME activities, such

as reading journals, attending a formal CME activity, and partici-

pating in a Web-based CME activity. Slotnick suggests that the

physician would ask the following questions:

— What’s important in all this information that I am hearing,

reading, or viewing?

— What experiences have other physicians had doing what I am

hearing about?

— What is the best way to learn?

At the end of this stage, a physician has evaluated the problem or

question that precipitated the search for learning resources, deter-

35

Moore

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 35

mined whether pursuing learning would be beneficial, and decided

what type of learning to pursue.

Stage 3: Engaging in learning

During the entire five-stage process, a physician manages the pattern

of formal and informal resources that he or she finds most effective

to address the opportunity for learning that started the process.

43

Learning becomes more focused, intentional, and formal during this

stage. Physicians learn informally as well as in formal settings.

44

Informal learning consists of (but is not limited to) casual journal

reading, ad hoc conversations with colleagues, interactions with

industry representatives, and attendance at grand rounds and other

regularly scheduled conferences. Some informal CME focuses on

specific patient problems and is more structured, such as consultations

with colleagues and focused reading of journals or textbooks. Formal

CME is usually planned in some detail and consists of CME activities

planned by the physician learner or by someone else. Formal CME

activities planned by the physician learner would include preceptor-

ships in which educational activities are negotiated between the

learner and the preceptor and learning projects like the Maintenance

of Competence Program (MOCOMP) of the Royal College of Physi-

cians and Surgeons of Canada, in which a physician identifies an

opportunity for improvement, designs learning activities directed at

the improvement, and assesses accomplishments.

45–49

Other educa-

tional activities planned by the learner are those in the maintenance

of certification programs of specialty societies that are members of

the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).

50

CME activities

planned by others include formal CME courses and enduring materials.

Questions that emerge during this stage include but are not limited

to the following: “Is this educational activity addressing what I need

to learn?”; Is the content based on evidence from research?”; “What

do other participants think about what is being presented?”; How

does what is being presented relate to my patients?”; “Is this all I

have to learn?”; “Does what is being presented actually work?”; and

“How will what is being presented change my practice?”

Stage 4: Trying out what was learned

In this stage a physician begins to use newly learned skills and

knowledge to address the problem that precipitated the learning

36

How Physicians Learn and How to Design Learning Experiences for Them

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 36

process. During this stage a physician develops a favorable

opinion about what she has learned and makes a decision to

accept it or reject it. She experiments with what she has learned

in her practice setting but not before confirming the benefits of

what she has learned with colleagues. The stage begins with a

physician being less than comfortable with her new skills and

knowledge. As she progresses through the stage, however, she

will become more skillful and confident with what she is doing.

The stage is over when the physician is sufficiently comfortable

with the newly learned skills and knowledge and they become

second nature.

During this stage a physician is likely to rely more on her own

reflections and conversations with colleagues than the other resources

she used during the learning process.

51,52

Questions she might ask

during this stage include the following:

— How does what I have learned apply to my practice?

— What do I have to do in my practice to use what I have

learned?

— Am I doing it right?

— Does it work?

An important part of this trial and evaluation stage for a physician is

determining not only how to use what she has learned but also

whether it works in her setting. If the physician’s practice uses an

electronic medical record or other digital databases for monitoring

performance and patient outcomes, she will be able to determine

the effectiveness of the new learning. But it is more likely that she

will “reflect-on-her-practice” after several “experiments,”

16

and if the

new learning appears to be effective, will move on to the next stage.

This stage raises interesting ethical issues. One might ask what the

responsibility of a CME program is to ensure that every participant

has the opportunity to practice until confident in an environment in

which patients are not endangered by physician experimentation

“until he or she gets it right.”

Stage 5: Incorporating what was learned

During this final stage, a physician integrates what he has learned

into his daily routines; it will become a part of what he does when

37

Moore

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 37

How Physicians Learn and How to Design Learning Experiences for Them

38

managing patients. Questions that emerge in this stage include but

are not limited to the following: What do I have to do differently

in my practice to use what I have learned? How do I make what I

have learned a part of my practice? What office routines have to

be changed? What new procedures have to be introduced? What

training does staff need? And, what do I have to do for my patients?

If the physician has not done so already in the previous stage, during

this stage, a physician will have to make sure that office routines

and procedures include not only what he has learned but also what

he will need to implement what he has learned. Most important, he

will need to train his staff in what he has learned.

Principles for Facilitating Physician Learning in Formal CME

As the research summarized here suggests, physician learning is

predominantly self-directed. Physicians engage in CME activities

because they want to learn something that will help them provide

the very best possible care to their patients, not because someone

has told them what to learn. In most cases, physicians proceed on

their own through the five stages of self-directed learning described

here, consulting a variety of resources, but essentially planning and

directing the learning project in which they are engaged on their

own. In many cases, physicians choose to enroll in a formal CME

activity that has been planned by someone else. The most effective

formal learning experience for physicians would take into account

where a physician is in his or her learning process (what stage) and

what will help him or her accomplish learning goals. The principles

summarized in the following paragraphs are drawn from the studies

reviewed in the previous section of this monograph as well as from

studies that have examined learning in general.

Principle 1: Planners of formal CME should consider physicians’

stages of learning.

Typically, CME planners asssume that all physicians who enroll in a

CME activity are at stage 3, engaging in learning, and need informa-

tion. In reality, a physician who enrolls in a formal CME activity

could be at any one of the five stages of learning and would have

questions related to his stage (Table 2). To make the learning expe-

riences of physicians more productive, CME planners should help

physicians recognize what stage they are in and plan activities to

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 38

Recognizing

an Opportunity

f

or Learning

Searching for

Resources

f

or Learning

Engaging

in Learning

Trying Out

What Was

L

earned

Incorporating

What Was

L

earned

Am I treating patients

(

in this disease area)

correctly?

H

ow are my patients

(in this disease area)

doing?

What are the

a

cceptable standards

o

f care (in this

disease area)?

Is there anything

“new” in this

disease area?

What’s important

in all this information

that I am hearing

about this disease

area?

Is this a problem

f

or me?

D

oes this problem

have a solution that

can be addressed

b

y learning?

Are there resources

a

vailable for learning

t

he solution?

Can I learn the

solution?

What’s important

in all this information

that I am hearing

about this disease

area?

What do I need to

learn?

What is the best way

to learn?

What experiences

have other

physicians had

with this problem?

How will learning the

solution change my

practice?

Is this educational

a

ctivity addressing

what I need to learn?

I

s the content based

on evidence?

What do the other

p

articipants think

a

bout what is being

presented?

How does what

is being presented

relate to my

patients?

Is this all I have

to learn?

Does what is being

presented work?

How will what is

being presented

change my practice?

How will what is

being presented

change my practice?

Am I doing what

I

am learning

correctly?

H

ow will I be able

to do what I am

learning in my

p

ractice?

Does what I am

l

earning to do work?

What do I have to

d

o differently to use

what I have learned

in my practice?

H

ow do I make what

I have learned a

part of my practice?

What office routines

h

ave to be changed;

w

hat new

procedures have

to be introduced?

What training does

staff need?

What do I have to

do for patients?

What do I have to

do for patients?

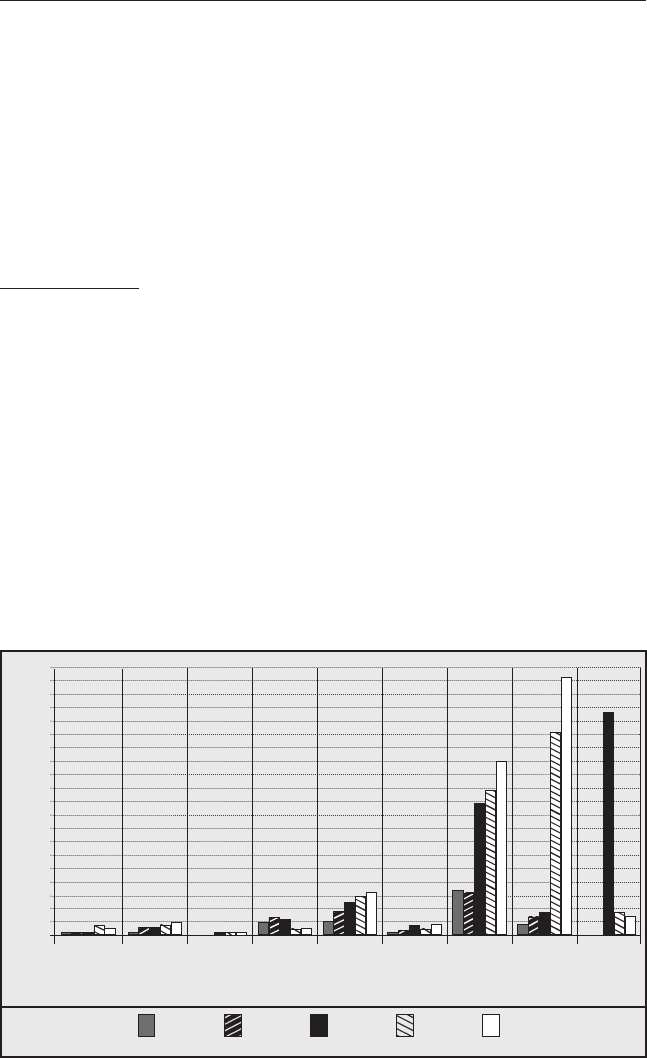

Table 2. Questions Physicians Have at Each Stage of Learning

Adapted from Slotnick

39

Moore

39

address the questions they have that are associated with that stage.

A physician would initiate the five-stage learning process for

problems related to specific patients and for more generalized

patient-related issues. The process that results for each is slightly

different. For problems related to specific patients (Why is Mrs.

CEHP 5-9 with final edits (forhiresPDF):050306 NeuroMngrph11/17/05AA 5/9/08 5:36 PM Page 39

Jones not responding to her hypertension medication?), a physician

would likely use resources in his office (journals, textbooks, online

resources) and local consultants in almost all stages. The physician