1

Linkages: Development Strategies, Governance and Cooperation

A Comparative Perspective of Thailand and Cambodia

The Greater Mekong Subregion Capstone

Capstone Director: Professor Francois Bafoil

Capstone Researchers

Mohamed Abdul Aziz

Wei Li

Zoe Sinclair

Jinglong Yang

2

Executive Summary

This capstone has set out to understand the relationship between Special Economic Zones (SEZ), or Industrial Estates

(IE), and regional integration. Additionally, it looks at their role as vehicles for investment, particularly Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI), and links to growth. Initially the report analyses the concept of regional integration, the types and

ways of regional integration, and its context in the Greater Mekong Subregion(GMS). The issue of zones will be

considered which have a regional history and country specificities. Based on our conceptual research and field research,

this report will then expand on the factors involved in each issue and the flow-on effects – from resources and

governance to the implications of FDI and potential for value chains.

Regional Integration

Regional integration has been increasingly seen as a potential development tactic. But its forms, factors and implications

vary according to context. The Association of South-East Asian Nations, or ASEAN, was established in 1967 and expanded

over the years to its current form of ten member states: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei

Darussalam, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia. From its early stages, ASEAN was aimed at accelerating economic

growth and expanding trade

1

. As a result, ASEAN's concept of regional integration has predominantly been focused on

the market. Additionally, due to characteristics such as its policy of non-interference and a respect for sovereignty, there

has been little interest in the development of supra-national institutions. As such it has evolved to a relatively shallow

form of regional cooperation where briefings and meetings are regularly held and consensus occurs on a policy of

mutual interest. Plans for an ASEAN economic community are continually pushed back, although the most recent ASEAN

annual report places the goal at 2015.

The inclusion of the so-called CLMV states (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam) had implications for ASEAN due to

their low GDPs. ASEAN took a number of steps to aid growth in these countries such that they might be more in-line

with the rest of the members. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) developed a specific GMS programme which also

includes the two south-western Chinese provinces of Yunnan and Guangxi. In 1992, the GMS Economic Cooperation

Program (GMS-ECP) was launched with the support of Asian Development Bank (ADB), setting out “to promote

sustainable economic development through closer economic linkages between its member states.

2

” This vision is

embodied in the 3Cs strategy of enhanced “Connectivity”, increased “Competitiveness”, and a greater sense of

“Community”

3

.

In 2002, the GMS countries compiled a strategic framework for subregional development based on sector priorities and

programmes. It focused on strengthening infrastructure linkages, facilitating cross-border trade and investment, and

1

Hussey, p. 1

2

Bafoil and Ruiwin, 2010, 80

3

ADB, 1996

3

enhancing private sector participation, developing human resources, as well as environmental protection. An integral

part of the program and ADB's work towards development in the region has been focused on infrastructure. As one ADB

official put it “roads are easier to build than cooperation”

4

. However, Economic Corridors (EC) are intended to be much

more than just roads but are “designed to attract investment and generate economic activities along a central transport

artery and the border regions.

5

” These corridors connect to SEZs and resources such as ports and major hubs. Priority

has also been placed on transport due to its role on regional development by enhancing trade and connectivity. The EC

approach to ‘development through connectivity’ was adopted by GMS countries during the 8

th

GMS Ministerial Meeting

in Manila in 1998. The three phases to the realization of the EC are: building infrastructures; instilling the logistics, and;

initiating economic cooperation activities.

Three main EC, with several sub-corridors create a network connecting the subregion. These are the North South

Economic Corridor (NSEC), East West Economic Corridor (EWEC), and Southern Economic Corridor (SEC). Along with

connectivity to key resources and zones, these corridors connect the GMS with the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean –

providing connections to South and East Asia.

This development of hardware has been accompanied by 'software', most notably the Cross-Border Transport

Agreement (CBTA). This connection of infrastructure with software is important as it has been realised that many of the

benefits of infrastructure are held back by time and costs at borders. For this reason, the CBTA was not only important

but also significant for bringing together the region's leaders to a common agreement on the issue. The CBTA includes:

allowing through permits the movement on specific routes of vehicles, goods and license recognized drivers; using

single-stop and single-window inspection to reduce transaction time by providing advance and clear information on

clearance; providing customs transit, and guarantee system to avoid costly transhipment, and; enhancing CBTA effects

by increasing CBTA checkpoints

6

.

However, beyond the initial signing, members have not ratified all the principles contained within the CBTA and the

agreement's success has been limited. Furthermore, the agreement has not been incorporated in all the national laws.

While there are limitations to its success at a national level, there are also problems with its implementation at the local

level. The capacity of the local border authorities is weak, and the role of the private sector in complementing the

process is also lacking.

SEZs and Industrial Estates

SEZs are areas allocated within a country where the laws are more liberal to create an encouraging investment climate.

Specifically, they are identified by characteristics including: a large developed site; infrastructure and services; sale and

lease of factory buildings; control which allows benefiting the occupants and wider community

7

. In Cambodia, these

areas are called SEZs; while in Thailand they are Industrial Estates (IEs). While they have a number of differences, as will

be shown, their similarities are sufficient that they can be defined as economic zones. When convenient for discussing

both, they will be referred to as just 'zones'.

The development of industrial estate across Asia, as a tool for economic development especially in regional areas, began

in Singapore in 1951

8

. Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Thailand followed in the main wave in the 60s, but it is the Chinese

model that has gained the most recognition. The successes of these growth models have been replicated elsewhere with

4

Jean-Pierre Verbiest, speaking at GMS forum at CERI, 2011.

5

Bafoil and Ruiwin, 2010, 80

6

ADB, Greater Mekong Subregion Cross-Border Transport Facilitation Agreement, 4

7

Cited in Aveline-Dubach, p.175

8

Aveline-Dubach, p.175

4

varying successes and many differences

9

. It is estimated that are some 3,000 zones in 135 countries today, accounting

for more than 68 million direct jobs and more than $500 billion of direct trade-related value added within zones

10

.

Within the GMS, zones have been seen as tools to attract investments, create jobs, and boost industry competitiveness,

aimed at enhancing economic growth. Thailand was an early adopter and Cambodia has since also created a number of

SEZs. The subregion, particularly with ADB's infrastructure creation, as aimed for the zones to form key poles of growth.

As such, they form key points along the economic corridors, including at border areas and near key resources such as

ports. This strategy behind the zones’ locations often ties their success to the development of the corridors and the

corridors success. These links, between the corridors, zones, resources and growth, will be examined as part of this

report.

Industrial Policy

Industrial policy is seen as a critical strategy towards industrial and economic development. It is linked to economic

growth, employment and income. Often it is focused on particularly sectors and growth is generated from those

linkages. In particular, the stage of development of a country is often identifiable by industrial policy and its level of

technology. This often starts as absorption by developing countries, and they can experience a significant catch-up effect

by doing so

11

. FDI is often a key way by which technology is introduced to a country and firms. However, the links

between FDI, technology and improvements for local firms require a complex balance of factors including government

support and policies that push for integration into the value chain. By improving technological status, and innovation, it

is possible enhance the value-add to products, and thus for firms and the country to move up the value chain. Related

policies to achieve this often involve improving efficiency, capacity, innovation and linking upstream and downstream

economic activities.

12

However, each industry has differences in technology and in skills needs. The various different

approaches of developing the industry have been called industrial policy. Other critical components are macroeconomic

policies, sectoral polices and the investment climate. In the case of this report, the investment climate can be viewed

through the zones which are designed as a vehicle for investment. This thus links industrial policy to its role for growth,

the zones and regional integration. As this report will demonstrate, Thailand has essentially failed to upgrade and

incorporate an industrial policy that supports education and vocational training towards skills improvements and

innovation. Furthermore, there was limited support for entrepreneurs or state companies and a lack of place-based

policies to support the zones. Cambodia faces an issue of diversifying and strengthening its sectors for growth.

Government involvement in industrial policy is also extremely limited.

Case studies

Thailand and Cambodia share a number of commonalities and differences, both of which serve to make them

worthwhile case studies. Given this report's focus on regional integration, it was important to focus on studies that are

involved in ASEAN and GMS so as to examine their reasons for involvement and constraints to integration. Their

relations to each other are also interesting given their proximity, shared borders and gulf and other similarities.

Thailand's growth and development, based on FDI and comparative advantages of low cost labour, occurred during the

1980s and 90s. Crucial institutions were the Board of Investment and the Industrial Estate Authority Thailand (IEAT).

Zones and incentive schemes followed, aimed at encouraging development outside Bangkok. Cambodia, meanwhile,

has focused on developing various sectors and encouraging SEZs. The zones have typically been located near borders

although the most successful ones are centred around the key hubs and resources including Phnom Penh and

9

Aveline-Dubach, p.176

10

World Bank, 2008.

11

Kraemer-Mbula. E, Wamae.W (2010) ‘Innovation and the Development Agenda’, OECD, pp 40

12

Whitfield p.7

5

Sihanoukville. Cambodia also has a strong open market approach that has led to private investment in the zones but has

not translated to development.

Thailand has the highest GDP in the GMS and has witnessed successful growth over the past decades. Just as it has

learned through developments in East Asia, it too can serve to provide lessons to those less developed countries.

Theoretically, development stages were expected to progress similarly in different countries but there is a clear need for

contextualisation. Cambodia as a Less Developed Country (LDC) makes possible for a contrasting case and can

potentially learn from Thailand's successes and mistakes. However, it has its own characteristics, including a smaller

population and as such smaller domestic market and labour force. Given that many of the investors in Thailand started

there because of the domestic market, especially the Japanese, this could prove a critical difference for Cambodia.

Governance in Cambodia is also lacking, and similarly is capacity. The case studies illustrate the various advantages but

also challenges the countries have. With these in mind, it is possible to see their growth paths and strategies and the

implications for regional integration.

Conclusion

Regional integration, particularly with respect to Thailand and Cambodia, has been very limited. When considering these

factors of regional integration - hard and soft elements of infrastructure and cooperation – the concept is not fully

present.

Growth and development have been considered an important part of integration – in terms of allowing for it by having

countries of relative size and levels to provide a context for integration; and in terms of encouraging integration by

opening up new markets. As a tool for growth and development, the development of industrial estates has been the

key. Thailand was an early starter in this field but Cambodia too has developed a model of Special Economic Zones. As

such, we are interested in investigating industrial estates and special economic zones to understand growth and regional

development. The zones also rely on resources, access to markets, and good policies. Given this, they provide a way of

assessing these elements and regional integration. The zones also act as vehicle for FDI which has been attributed as one

of the main reasons for Thailand's growth. However, Thailand's growth has slowed and it faces challenges. What is

stopping the industrial estates policy from continuing the growth?

Given the role of FDI in SEZs, the actors and their influence need to be considered. The role of MNCs in the region's

zones, and globalisation, introduces the issue of value chains. Value chains have an impact on regional and international

integration and needs to be assessed as an additional influence on the process of integration.

This paper will argue a number of points, including that a) regional integration has been limited. This is due to political

economies and regional economic disparities, and secondly, to limited state capacity and governance. The report will

also illustrate that b) SEZs as a successful growth model are subjective to certain conditions c) an effective industrial

policy is needed to complement SEZs d) The private sector has a critical role and influence on growth and regional

integration through a need to establish value chains.

6

Contents

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................................... 10

List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................................... 12

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... 15

Chapter I: General perspective ............................................................................................................................................. 18

1.1 Regional Integration and South East Asia ....................................................................................................................... 18

ASEAN................................................................................................................................................................................ 18

Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS) .................................................................................................................................. 20

1.2 Four Pillars ....................................................................................................................................................................... 22

Strategy ............................................................................................................................................................................. 22

Physical connectivity ......................................................................................................................................................... 23

Tax Incentives and Tools ................................................................................................................................................... 25

Governance ....................................................................................................................................................................... 27

1.3 Regional Integration Analysis .......................................................................................................................................... 29

1.4 SEZs as a vehicle for growth and investment.................................................................................................................. 31

1.5 Why Cambodia and Thailand .......................................................................................................................................... 35

Chapter II: Thailand ............................................................................................................................................................... 39

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... 40

2.1 General framework ......................................................................................................................................................... 44

2.1.1 History ...................................................................................................................................................................... 44

2.1.2 Geography ................................................................................................................................................................ 48

2.1.3 Resources ................................................................................................................................................................. 49

2.2 Industrial policies and actors .......................................................................................................................................... 50

2.2.1 Industrial policy ........................................................................................................................................................ 50

2.2.2 Industrial Estates ...................................................................................................................................................... 51

2.2.3 Institutions ............................................................................................................................................................... 52

2.2.4 Investors ................................................................................................................................................................... 54

7

2.3. Case Study: Amata City Industrial Estate ....................................................................................................................... 58

2.3.1 Investment climate .................................................................................................................................................. 61

2.3.2 FDI ............................................................................................................................................................................ 61

CP Group Profile ............................................................................................................................................................ 64

2.4 Assessment ..................................................................................................................................................................... 65

2.4.1 Institutions ............................................................................................................................................................... 65

2.4.2 Value chains ............................................................................................................................................................. 67

2.4.3 Good Governance .................................................................................................................................................... 68

2.4.3 Regional Integration ................................................................................................................................................. 69

Chapter III: Cambodia ........................................................................................................................................................... 72

3.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 73

3.2 Industrial sectors ............................................................................................................................................................. 74

3.2.1 Garment ................................................................................................................................................................... 74

3.2.2 Construction ............................................................................................................................................................. 75

3.2.3 Agriculture (Agro-industry) ...................................................................................................................................... 75

3.3 Economic reform ............................................................................................................................................................. 77

3.3.1 Privatization of SOE .................................................................................................................................................. 77

3.3.2 Attracting FDI ........................................................................................................................................................... 77

3.4 Investors .......................................................................................................................................................................... 79

3.4.1 Chinese Investment in Cambodia ............................................................................................................................ 79

3.4.2 Japanese Investment in Cambodia .......................................................................................................................... 80

3.4.3 Value Chain .............................................................................................................................................................. 81

3.5 SEZs (Industrial Estate) in Cambodia ............................................................................................................................... 83

3.5.1 Summary .................................................................................................................................................................. 83

3.5.2 Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (PPSEZ) .......................................................................................................... 89

3.5.3 Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone (SSEZ) ............................................................................................................ 93

3.5.4 Sihanoukville Port Special Economic Zone (SPSEZ) .................................................................................................. 97

3.6 Key findings ................................................................................................................................................................... 101

8

3.6.1 The comparative advantages of Cambodia ........................................................................................................... 101

3.6.2 The main obstacles of Cambodia ........................................................................................................................... 102

3.7 Sub conclusion .............................................................................................................................................................. 107

Chapter IV: Comparison of Thailand and Cambodia ........................................................................................................... 110

4.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 111

4.2 Governance ................................................................................................................................................................... 113

4.2.1 Institutional arrangement ...................................................................................................................................... 113

4.2.2 Capacity .................................................................................................................................................................. 114

4.3 Incentives ...................................................................................................................................................................... 117

4.4 Resources ...................................................................................................................................................................... 119

4.4.1 Labor ...................................................................................................................................................................... 119

4.4.2 Infrastructure ......................................................................................................................................................... 120

4.5 Strategy ......................................................................................................................................................................... 122

4.5.1 Overall strategies ................................................................................................................................................... 122

4.5.2 Investment ............................................................................................................................................................. 123

4.6 Regional integration ...................................................................................................................................................... 125

4.6.1 EC and CBTA ........................................................................................................................................................... 125

4.6.2 Integration vs non-integration ............................................................................................................................... 126

4.6.3 Constraints for regional integration ....................................................................................................................... 127

4.7 Sub conclusion .............................................................................................................................................................. 130

Chapter V: Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................ 131

5.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 131

5.2 Thailand ......................................................................................................................................................................... 131

5.3 Cambodia ...................................................................................................................................................................... 132

5.3.1 Governance ............................................................................................................................................................ 132

5.3.2 Infrastructure ......................................................................................................................................................... 137

5.3.3 Labor ...................................................................................................................................................................... 138

5.4 Regional integration ...................................................................................................................................................... 140

9

5.4.1 Thailand .................................................................................................................................................................. 140

5.4.2 Cambodia ............................................................................................................................................................... 140

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................................... 143

Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................................................ 144

10

Acknowledgements

This report is the production of nearly one year collaboration between four Master of Public Affairs students at Sciences

Po, Paris.

Professor Bafoil, Director of Research at the Centre for International Research (CERI) and capstone leader, was of great

support. His guidance during the research, and comments on our draft, made a difference in our work.

Grateful thanks also go to both Mr. Jean-Pierre Verbiest of Asia Institute of the Technology and Dr. Hang Chuon Naron of

the Ministry of Economy and Finance of Cambodia. They gave us a very useful introduction and insight to the two

countries as well as assisting with coordination of interviews. Without this assistance, especially in Cambodia, we would

not have had access to many interviewees, particularly government.

A great deal of gratitude also goes to the people whom we interviewed during our trip in Thailand and Cambodia in

January 2012. We are especially grateful for their welcome, support, advice and information. Without them our work in

Southeast Asia would not have been as fruitful as it was.

Last but not least, we would like to also thank the 2011 MPA capstone team who worked on the Greater Mekong Sub-

region topic. The advice they provided about the field trip and the capstone report was a useful reference.

11

List of interviews

Date/time

Department/Firm

Name

Position

Thailand

01-09-2012

National Research Council

Chieanchuang Audi

Kalayanamitr

Businessman/advisor

International Affairs Bureau, Office of the Board of

Investment

Vasana Mututanont

Executive Director

01-10-2012

Charoen Pokphand Group Company Limited.

Sunthorn Arunanondchai,

CBE, Vice Chairman

Industrial Business Development, AMATA

Corporation PCL

Satha Vanalabh-patana

Department Manager

Vatchariya Ngaotheppitak

Business Development Officer

01-11-2012

Thailand Resident Mission

Rattanatay Luanglatbandith

Economist (Regional Cooperation)

University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce

Dr. Pussadee Polsaram

Head of School of Business

Cambodia – Phnom Penh

01-12-2012

Supreme National Economic Council

Ministry of Economy and Finance

Dr. Hang Chuon Naron

Vice Chairman

Secretary of State

Department of Investment and Cooperation

Ministry of Economy and Finance

Pen Thirong

Director

Cambodian Special Economic Zone Board, Council

for the Development of Cambodia (CDC)

Chea Vuthy

Deputy Secretary General

Ministry of Public Works and Transport

Tauch Chankosal

Secretary of State

Vasim Sorya

Planning and Administration General

Department,

Director General

Chan Dara

Planning and Administration General

Department, Deputy Director General

Cambodia Resident Mission, ADB.

Peter J. Brimble

Senior Country Economist

01-13-2012

Phnom Penh Governor’s Office

Huot Hay

Deputy Director of Administration,

Responsible for Investment, Planning and

Waste Management Division

East Asia and Pacific Region, World Bank

Huot Chea

Senior Economist

Cambodia Chamber of Commerce

Ngoun Meng Tech

Director General

Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (PPSEZ)

Hiroshi Uematsu

Managing Director

PP SEZ

Minebea Cambodia

Kengo Katsuki

Vice President (COO)

Cambodia – Sihanoukville

01-16-2012

Sihanoukville Governor,

Ministry of Interior

Sbong Sarath

Governor of Preah Sihanouk Province

Sihanoukville Training Center of National

Employment Agency

Ton Shina

Accountant

Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone (SSEZ)

Michelle Zhang

Department of CSR, Manager

Amy Yan

Overseas Marketing Department

Vice Section Chief

Sihanoukville Office of the Ministry of Public

Works and Transport

Nub Heng

Head of Office

01-17-2012

Sihanoukville Office of the Ministry of Labour and

Vocational Training

Yow Khemara

Director, Department of Labour, Sihanouk

Province

Sihanoukville Autonomous Port (PAS)

Lou Kim Chhun

Delegate of the Royal Government in Charge

as Chairman and CEO, PAS

Norng Soyeth

Director, Marketing and SEZ Department, PAS

12

List of Acronyms

ADB – Asian Development Bank

ADBI- Asian Development Bank Institute

ADF – Asian Development Fund

AEC- Asian Economic Community

AFTA – ASEAN Free Trade Area

AIT- Asian Institute of Technology

ASEAN – Association of Southeast Asian Nations

ASW- ASEAN Single Window

BSEZ - Bavet Special Economic Zone

CDC - Cambodia Development Council, which heads the Sub-committee of the Cambodian Special Economic Zone (SEZ)

Board

CBTA - Cross Border Transport Agreement

CLMV- Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam countries

EC - Economic Corridors

EWEC – East–West Economic Corridor

FDI- Foreign Direct Investment

GMS - Greater Mekong Sub-Region Program

GDP - Gross Domestic Product

HR - Human Resources

IICBTA – Initial Cross Border Agreement

MICL - Medtecs International Corporation Limited

MSEZ - Manhattan Special Economic Zone

MRC – Mekong River Commission 14

OSS – One Stop Service

PPSEZ - Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone

SCGT - Southern China Growth Triangle

SEAME - Southeast Asia Ministers of Education Organization

SEA - South East Asian

SEZ - Special Economic Zone

SFA-TFI – Strategic Framework for Action on Trade Facilitation and Investment

SPS - Sanitary and Phytosanitary Stop

SSI- Single Stop Inspection

SIJORI- Singapore, Johor and Riau growth triangle

R&D- Research and Development

TFWG - Trade Facilitation Working Group – GMS

TTF- Trade and Transportation Facilitation

UJIC - Universal Joint International Group

UNESCAP – United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

13

Chart of Figures*

Figure 1: Ports and Airports in GMS......................................................................................................................................................... 24

Figure 2: Expected GMS Power Interconnection in 2025 ........................................................................................................................ 24

Figure 3: Tax incentives and tools in GMS countries, Source: doing business in Asia and interviews in field trip .................................. 25

Figure 4: Governance model .................................................................................................................................................................... 27

Figure 5: Comparison of Socio-Economic Indicators: Thailand and Cambodia ........................................................................................ 35

Figure 6: GDP and GDP per capital in GMS .............................................................................................................................................. 36

Figure 7: GDP growth rate in GMS ........................................................................................................................................................... 36

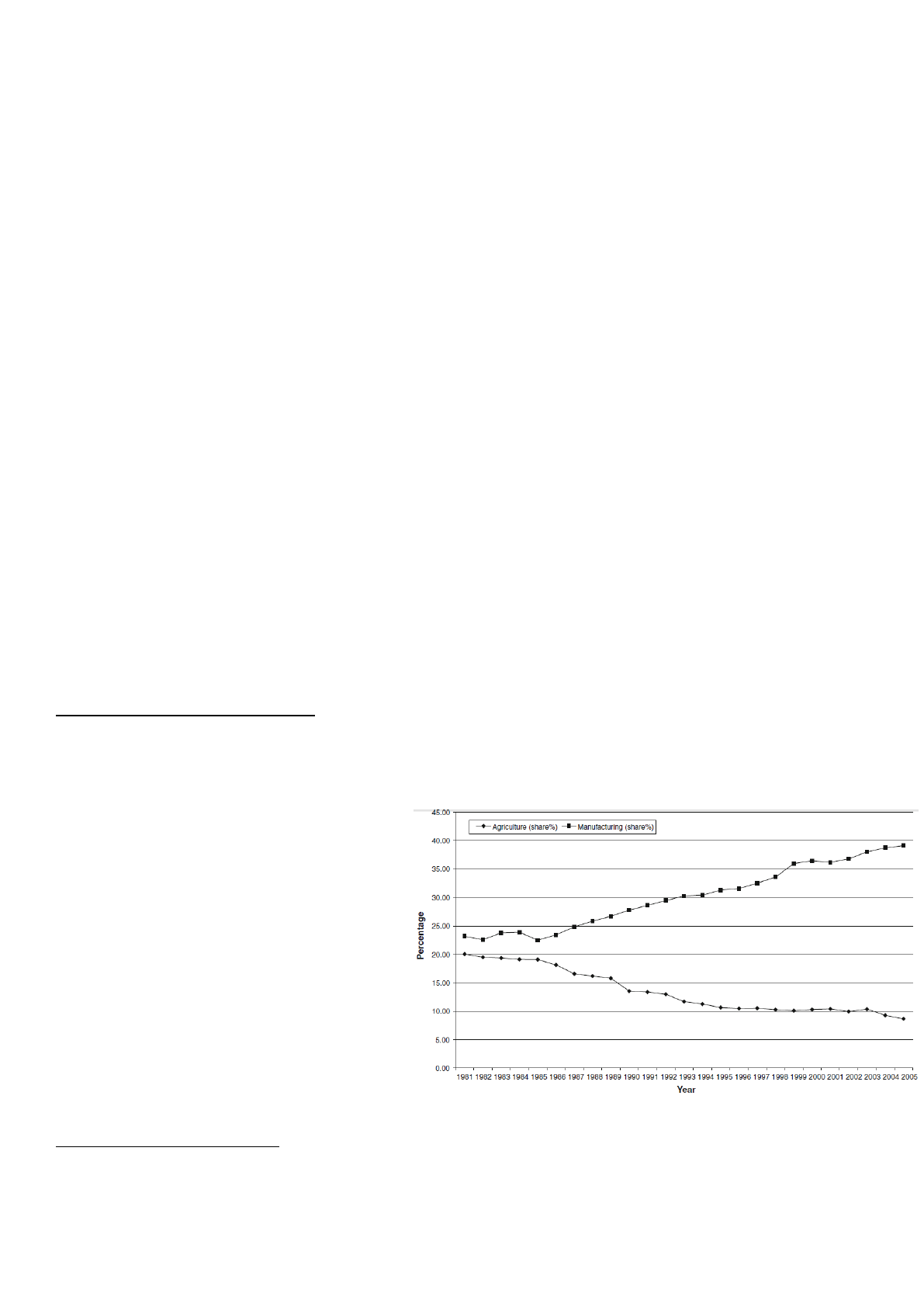

Figure 8: Economic growth in Thailand between 1980-2005, Source: Apisek Panuwan and Jayant Routray (2010) .............................. 41

Figure 9: Structural Change in Thailand Economy. Source: Apisek Panuwan and Jayant Routray (2010) ............................................... 42

Figure 10: Net Flow of FDI in Thailand by Sector 1970 - 1995 ................................................................................................................. 43

Figure 11: Distance of some key destinations from industrial estates .................................................................................................... 44

Figure 12: Transportation and key destinations from Chon Buri and Rayong IEs ................................................................................... 45

Figure 13: Investment incentives in Thailand .......................................................................................................................................... 46

Figure 14: Electricity fees ......................................................................................................................................................................... 47

Figure 15: Water tariffs ............................................................................................................................................................................ 47

Figure 16: Locations of zones ................................................................................................................................................................... 48

Figure 17: GMS Economic Corridors ........................................................................................................................................................ 48

Figure 18: Technological and Innovative Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 50

Figure 19: Amata City location (source:http://www.business-in-asia.com/amata_industrial_estate.htm) ........................................... 58

Figure 20 : Amata City warehouses (source: http://www.amata.com/eng/corporate_history.html) .................................................... 58

Figure 21: Master Plan of Amata ............................................................................................................................................................. 59

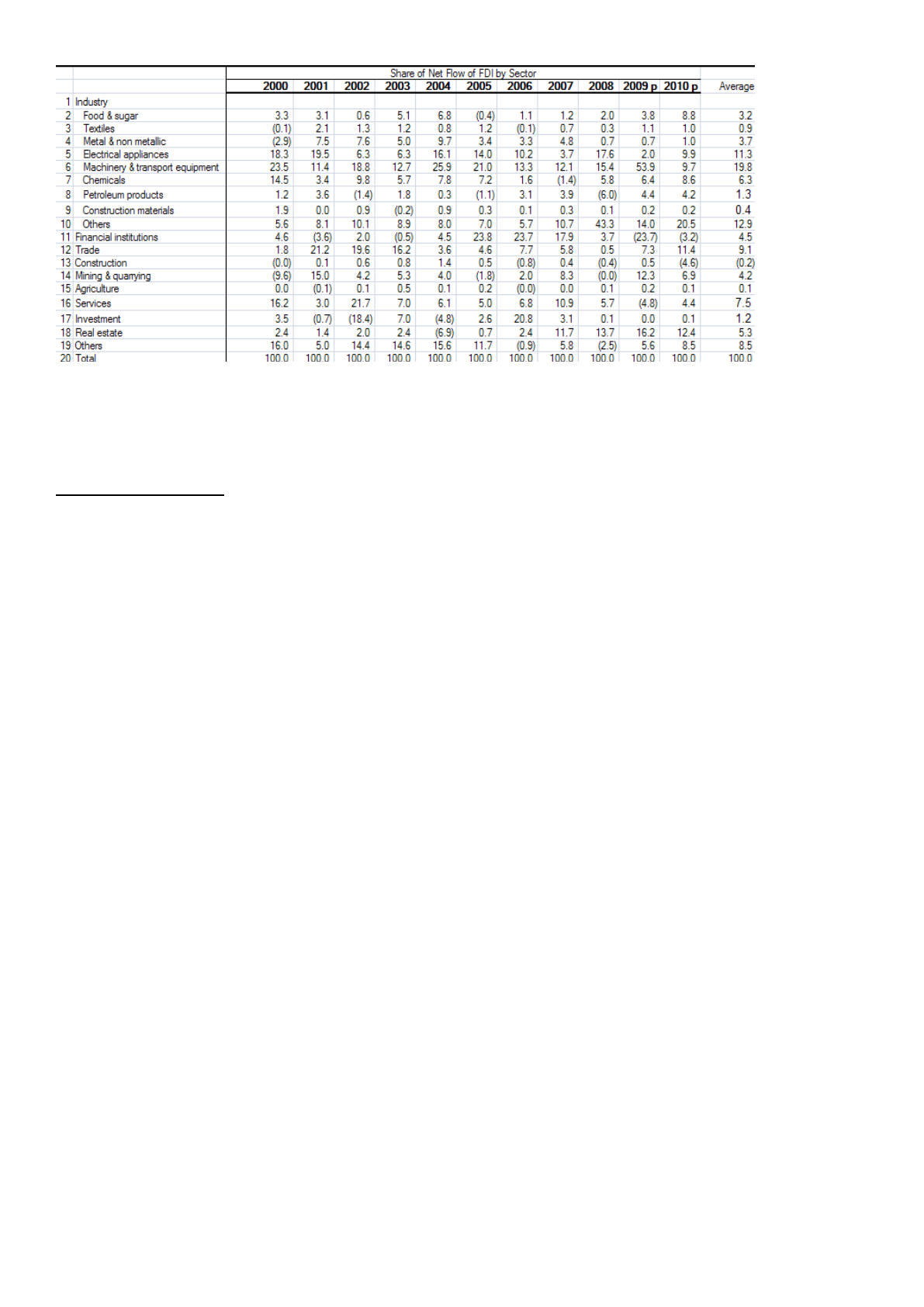

Figure 22: Share of Net Flow of FDI by Sector ......................................................................................................................................... 63

Figure 26: Garment sector employment (Unit: Thou) ............................................................................................................................. 74

Figure 27: Cambodia's Garments and Textiles Export (Unit: Million USD) .............................................................................................. 75

Figure 28: Trend of FDI and FDI-Gross Fixed Capital Formation Ratio ..................................................................................................... 78

Figure 29: Investment Trends by Country in Cambodia 1994-Oct2010 ................................................................................................... 78

Figure 30: Japan's ODA disbursements to Cambodia (Net disbursements, USD million) ........................................................................ 81

Figure 31: Location of SEZs in Cambodia ................................................................................................................................................. 83

Figure 32: List of SEZs in Cambodia.......................................................................................................................................................... 84

Figure 33: Organisation chart of SEZ program ......................................................................................................................................... 85

Figure 34: Structure at CDC and at each SEZ ........................................................................................................................................... 86

Figure 35: Incentives in the SEZs .............................................................................................................................................................. 87

Figure 36: Comparison of Cambodian SEZs ............................................................................................................................................. 89

Figure 37: Utility cost in Cambodian SEZs ................................................................................................................................................ 89

Figure 38: PPSEZ ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 89

Figure 39: Location of PPSEZ .................................................................................................................................................................... 90

Figure 40: Organisation structure ............................................................................................................................................................ 90

Figure 41: Development Phase of PPSEZ ................................................................................................................................................. 91

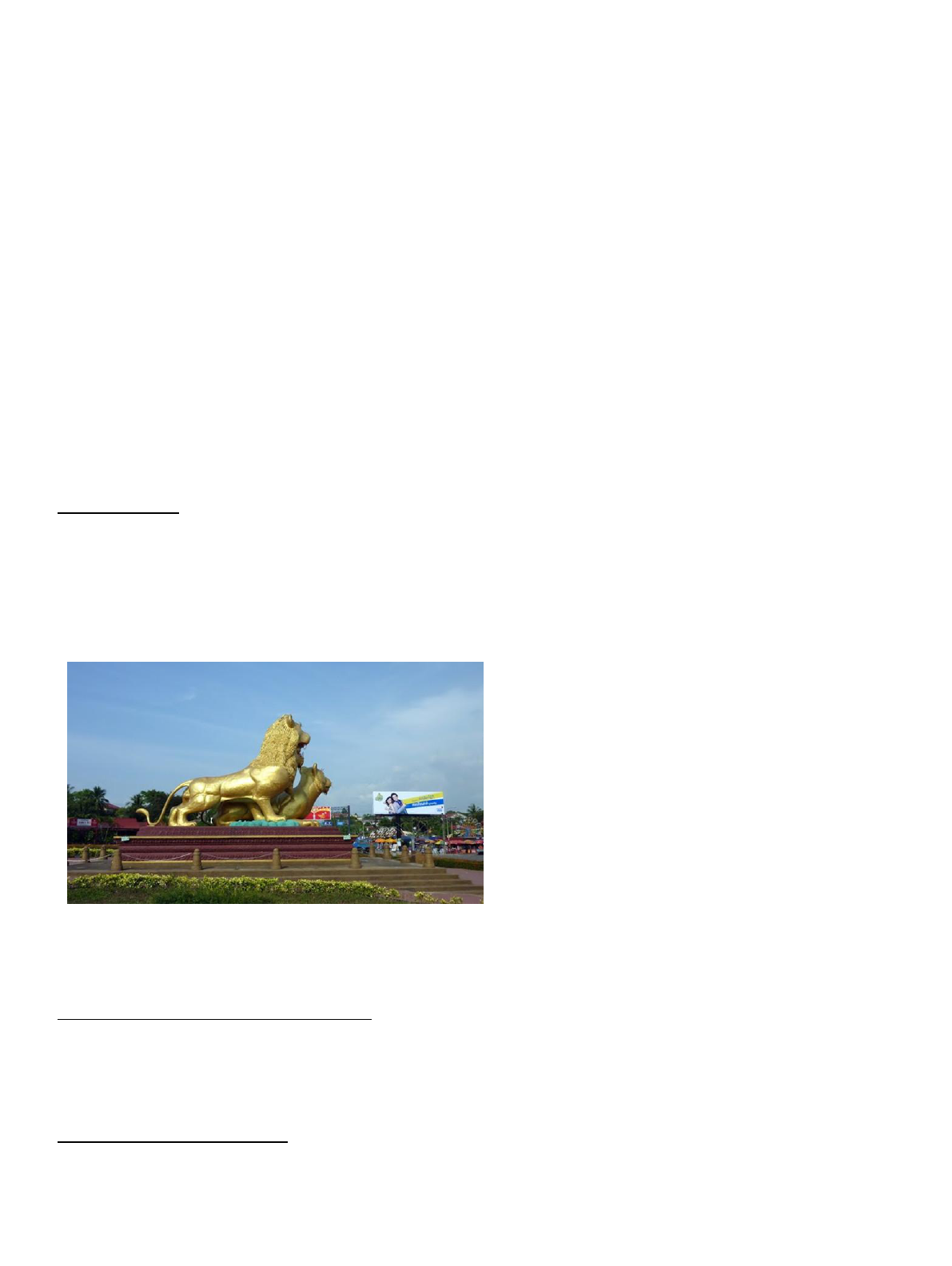

Figure 42: Sihanoukville city .................................................................................................................................................................... 93

Figure 43: Location of SSEZ ...................................................................................................................................................................... 94

Figure 44: The Gate of the SSEZ ............................................................................................................................................................... 94

Figure 45: Illustration of plan of SSEZ ...................................................................................................................................................... 95

Figure 46: Garment factory in SSEZ ......................................................................................................................................................... 95

Figure 47: Firms list in SSEZ ...................................................................................................................................................................... 96

Figure 48: Location of SPSEZ .................................................................................................................................................................... 97

Figure 49: Cargo Throughput of the Sihanoukville Port ........................................................................................................................... 97

Figure 50: SPSEZ ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 98

Figure 51: Management structure of SPSEZ ............................................................................................................................................ 98

14

Figure 52: Master plan of SPSEZ .............................................................................................................................................................. 99

Figure 53: Comparative Monthly Minimum Wage for GMS Countries .................................................................................................. 102

Figure 54: Summary of comparison between Thailand and Cambodia in terms of four pillars ............................................................ 112

Figure 55: Comparison of tax incentives and tools between Thailand and Cambodia .......................................................................... 117

Figure 56: Main indicators about infrastructure comparison between Thailand and Cambodia .......................................................... 120

* This chart comprises all the images, graphs, tables and illustrations.

15

Introduction

This report aims to analyse the role of Special Economic Zones(SEZs), or Industrial Estates(IEs), and regional integration.

Given that regional integration has often been used as a development mechanism, and there is a critical role for

economic growth, drivers of economic growth will also be considered. This includes examining FDI and industrial policy.

These also have strong linkages with zones, both SEZs and IEs, as they often form vehicles for investment due to their

more liberal laws. Critical to these are considering the various factors involved: resources, governance and value chains.

This introduction will unpack these concepts named here before exploring the theory, and history behind them in the

General Perspective. The main component of this section is to present regional integration, its history in the region and

developments, the status quo of regional integration and the kind of regional integration. The report will then draw out

the implications of regional integration for the report before presenting the zones and the rationale behind the case

studies.

Regional Integration

This report considers regional integration in a number of ways. Beyond establishing in the general perspective that it is

very limited, it considers the role of key resources, particularly infrastructure. This is primarily due to its focus on

infrastructure as a means of encouraging growth and integration. The Economic Corridors were built along main roads

but designed to connect to SEZs and resources such as ports and major hubs. This priority on SEZs underlines their

importance towards harnessing the potential benefits from regional integration such as goods flows and connectivity. It

has been accompanied by ‘soft’ infrastructure, mainly the Cross Border Transport Agreement (CBTA). As will be shown,

the establishment of infrastructure has limited benefits without the accompaniment of agreements to improve the flow

of goods and transport at the least. The CBTA has been limited in a number of ways, including with ratification and also

at a local level. As such this report’s consideration of Economic Corridors and CBTA and SEZS and their linkages to

regional integration must consider both national and regional level policy and the firm or zone level. This is achieved

with documentation on policy statements indicating the level of ratification and similarly at the local level. Both are

complemented with field interviews talking to different actors. Senior government officials were important to

understand their constraints, capacities and policies. Interviews with firms and zone management provided an

understanding of their connectivity locally, in terms of resources, and regionally. Meetings also indicated their

perception of the potential role of regional integration, constraints and opportunities.

Drivers of Growth

SEZs/IEs

Zones have a links to growth, regional integration and investment. As was detailed, zones have played an important part

in plans for regional integration and function as poles with economic corridors. The zones act as a vehicle for investment

and have been successful in various scenarios as growth models but the factors encouraging the growth need to be

considered. Their design can often lead to clustering and innovation allowing countries to upgrade and move up the

value chain. Consideration must also be given to the types and effects of investment that flow from the zones.

FDI

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has typically had a strong role in encouraging growth, extending networks and

production chains. This was the case with Thailand and was critical to the development of industrial zones along the

Eastern Seaboard and in the sectors of automobiles and electronics. It is also key to increasing capital – an issue of key

16

concern to Cambodia. FDI’s links to technology are also important for allowing a country to develop, but it must be

harnessed.

Industrial policy

Industrial policy is also seen as a driver of growth and also indicative of a country’s strategy and policy capacity. From

this implications towards a country’s regional integration policy, capacity and governance in general, and indicate an

economy’s level of technology and place on the value chain.

Constraints

The environment within which these issues are being considered has a particular track of development, specifically

characteristic of the region. This includes the market-oriented approach and a trend towards economic regionalism due

to the prioritisation of economic growth as a strategy by ASEAN and ADB. It has implications for the extent of policies

supportive of integration, particularly soft infrastructure. Furthermore, there are issues of economic disparities, political

economies, and governance and state capacity which limit potential for integration. Ultimately, the result is that there is

limited regional integration and both Thailand and Cambodia face significant challenges for growth and in which these

key drivers need development.

Report Organisation

The report will cover four parts:

Part 1: This chapter, The General Perspective, considers the background and regional context. The paper will cover key

points of development for ASEAN and GMS and the kind of regional integration that has been developing. It will also

consider the four pillars, a tool designed to analyse critical aspects of the report: Strategy, Resources, Governance and

Incentives. The paper will present the rationale for examining Thailand and Cambodia as case studies. Generally,

Thailand is the most developed country in the region, while Cambodia is the least developed one; the former is the one

of the founder members of ASEAN, while the later is the last member of ASEAN; Thailand has experienced almost the

slowest economic growth rate, while Cambodia’s was the fastest. As such the countries provide for interesting

comparative cases. This section will also outline the grounds for focusing on industrial policies and zones to illustrate

and analyse regional integration. Finally, this part will present the research methodology.

Part 2 & 3: These chapters present the case study narratives and key findings. These sections focus on the field research,

examining in particular the industrial policies and estates in Thailand and Cambodia. Field research included interviews

with local governments, NGOs, enterprises, communities and other data. The cases will detail the development of

Thailand’s industrial policy and estates, the policy incentives and governances, investment climate and investors’

involvements, and development resources. This section will also analyse the key findings according to the case study of

the AMATA Zone. Regarding Cambodia, the study will focus on the development and performance of SEZs (industrial

estates). The paper will present three SEZs in Cambodia to analyse the main constraints and opportunities for

Cambodia’s industrial policies and estates. In addition, the chapters will cover the analysis of the countries’ main

investors, including Chinese and Japanese investors.

Part 4: This chapter forms the comparative part of the report. It analyses key aspects in Thailand and Cambodia

including institutional establishment, governance capacity and policy incentives among other factors. By using Thailand

as a potential model for Cambodia, it will allow for clarity on differences between the two and potential constraints for

Cambodia. This section will analyse the nature of different investors and their influence on local developments, including

the impact of Chinese and Japanese investors’ different strategies, performances and goals. Finally, this section will

17

assess the implications of these issues for regional integration to identify what Thailand and Cambodia should do to

achieve their development targets and improve regional integration.

Part 5: This concluding section, will propose relevant policy recommendations according to what has been established in

the analysis presented in the previous sections. This will include issues such as what Cambodia could learn from Thailand

and what Cambodia should do according to its endowments and place on the value chain, before a final conclusion.

Methodology

This report is a comparative - analytical research paper that explores SEZs and IEs and Industrial Policy as a focus in

regional and development literature; it draws from the research relevant models and typologies, and then identifies

both analytical and practical concerns regards to the industrial estates and industrial policies concerned and their roles

in accelerating regional integration and economic development.

The research process took place over an eight month period. In the first four months, the existing literature was

reviewed on the following topics: Regional Integration, Local Development, Special Economic Zones, ASEAN, Greater

Mekong Sub region, Investors’ Strategies, Background Summaries on each country along historical, political and social

lines, Economic Performance of these Countries and relevant fiscal data and trends on growth, trade and FDI etc.

Furthermore, to make the analysis clearer, we used big players’ strategies (involvement of Chinese and Japanese

investors), physical resources (infrastructure, natural resources), policy incentives and governance as four important

pillars to help us in identifying the key issues.

The primary sources of this report were cultivated through field research that took place over a 11 day visit to the two

countries including extended visits in the Four Industrial Estates (AMATA in Bangkok, SEZs in Phnom Penh and Sihanouk

Ville in Cambodia). During that process the group interviewed: Firms, Central and Local Government officials, Public

officers involved in SEZ organization, Developers of Industrial Estates, Education centre, Private actors, Expertises,

Consultant, NGOs, the World Bank and the ADB. There were additional interviews took place with experts in Paris during

the workshop of GMS, and in the last four months the report preparation phase was developed. The interviews were all

semi-structured interviews with primary sources of information, acknowledging the social interaction between

researchers and interviewees, including language barriers. Official data was collected as and when possible in a

systematic and non-intrusive way.

The main obstacles of the research were a) language barriers that affected the capacity to gather information; in turn

limiting our ability to develop strong relationship with interviewees and also restricting access to low management

workers and locals, both of which are key sources to understanding the conditions of labourers in the industrial estates

and b) insufficient time on the ground. Ideally, we would have been able to stay for a longer period of time in the region

as new actors are referenced in the process that we were unable to interview. There was a challenge since one of our

team members could not participate in the field trip because of diplomatic issues. However, the rest of team overcame

the constraint and improved cooperation and understandings by sharing more responsibilities.

18

Chapter I: General perspective

1.1 Regional Integration and South East Asia

Regional integration, and in particular regional trading groups, has been used as a development tactic more frequently

in recent years

13

. A World Bank report posits that the main goal of regional agreements is “reducing barriers to trade

between member countries”

14

and include the basic step of removing tariffs to non-tariff barriers and liberalization for

investment and potential economic union and shared institutions. The World Bank report charts a number of changes to

what it broadly terms Regional Integration Agreements including: a move from closed regionalism to a more open

model; a recognition that integration is more than reducing tariffs (in the GMS this refers to the ‘soft’ aspects such as

CBTA); and the development of North-South trade blocks.

One of the prime examples is the EU which had its origin in the European Coal and Steel Community before developing

into the European Economic Community. Its success is cited as causing other regionalism initiatives. The rationale

behind such initiatives are: conforming to better polices and signaling such to investors; access to markets; achieving

economies of scale for firms’ better access to labour and technology; safeguarding sovereignty by improving economic

standing; improve stability and prosperity in the region to avoid spillovers of negative issues

15

. Some of these can be

seen in ASEAN and the GMS, for example ASEAN was seen as a way to reduce tension between Indonesia and

Malaysia

16

. ASEAN officials have also been quoted as commenting on the creation of the organization as a vehicle for

attracting FDI

17

.

Theories that take into account the political, economic and institutional factors have attempted to explain how and why

regional integration occurs and what qualities define deep regional integration. The distinction has been made between

positive and negative integration whereby the latter involves the removal of discriminatory national economic policies

while positive refers to common institutions

18

. A stages approach is expected to progress as follows: free trade area;

customs union, economic union, total economic integration

19

. Finally, a distinction can be made between deeper

integration, beyond the removal of border barriers, and shallow integration, which is trade liberalization

20

. However,

ASEAN is generally seen as a relatively shallow form of regional cooperation where briefings and meetings are regularly

held and consensus occurs on a policy of mutual interest.

ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, was established on 8 August 1967 in Bangkok, Thailand, with the

signing of the ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) by Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.

Brunei Darussalam then joined on 7 January 1984, Viet Nam on 28 July 1995, Lao PDR and Myanmar on 23 July 1997,

and Cambodia on 30 April 1999, making up what is today the ten Member States of ASEAN.

13

Maurice Schiff and Winters, L. Alan, Regional integration and development, World Bank, 2003, p.ii

14

Schiff, p.1

15

Schiff, p.9

16

Schiff, p.192

17

Schiff, p. 7

18

Tan, Lay Hong, Will Asean Economic Integration Progress beyond a Free Trade Area?, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 4

(Oct., 2004), pp. 935-967, Cambridge University Press on behalf of the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, p.943

19

Tan, p.944

20

Tan, p. 944

19

ASEAN’s main goals were intraregional economic development, social progress and cultural development and regional

peace and stability, as the declaration came to reflect

21

. It also aimed to accelerate economic growth and expand trade,

particularly in the field of agriculture and industries.

The region’s enlargement occurred in three phases beginning in 1995 and today, the organization’s members have a

total population of approximately 600 million people and in 2010, its combined nominal GDP was US$1.8 trillion. The

inclusion of Cambodia, Laos and Viet Nam was seen as a change in the description of ASEAN members. These states

were transition economies and had significantly lower GDPs. It had posed concern for the economic development and

integration of the region although the addition of different industries and a diversified regional economy are now seen

as an advantage. The CLMV states were also given time to meet the region’s programmes, including reducing tariffs and

liberalizing services and investment.

A number of events and issues since ASEAN’s creation and the declaration have helped characterize the regional

organisation’s policies. These policies involve: non-interference, security, and integration. Developments to the policy on

non-interference came in 1998 and resulted in a principle of “enhanced interaction”

22

. Steps were taken for data

collection to better understand financial and economic situations nationally with a view to addressing them as regional

issues and an informal foreign ministers retreat was organized as a mechanism to frankly discuss issues of regional

importance

23

. The ASEAN Security Community (ASC) was created in October 2003 in recognition of transnational security

problems

24

.

Policy on the integration front has been focused on a number of developments including: demographics, financial crises,

and institutions. East Asia was concerned that they needed organizations and cooperation regionally to protect them

and prevent a reoccurrence of the Asian Financial Crisis

25

. Although the attempt by Japan to create an Asian Monetary

Fund in 1998 failed, the idea behind it was reflected in the strengthening of ASEAN and APT and the Chiang Mai

initiative

26

. There have also been more than 40 bilateral trade agreements since the crisis

27

. Following the approach of

the EU, it would seem institutions are an important step towards closer integration. However, the non-interference

policy and strong sovereignty has inhibited institution building. However, various crises within the region have required

the establishment of institutions, although typically on an “ad-hoc” basis. ASEAN has taken the approach, sometimes

considered “soft institutionalism”, of setting up regular forums and informal meetings in order to address issues of

concern.

In terms of steps towards regional development, and following from that increased integration, ASEAN began with three

economic projects, including, the ASEAN Industrial Projects (AIP) and the ASEAN Industrial Complementation (AIC)

project. The first was plagued by direction and project agreement problems, and financing issues. The second was

focused on the micro-economy and enhancing intraindustrial linkages and trade. Complex and lengthy processes

affected the success of this project. Trade barriers have also been an inhibiting factor. However, Preferential Trade

Arrangements was partly successful, especially for tariff preferences, although it progressed slowly on a product by

product basis

28

, and involved an extensive exclusion list

29

. Trade as a sign of integration has not evidenced increased

integration among ASEAN members as it is dominated by a few countries, mainly Singapore, and trade in minerals and

21

Antonia Hussey, Regional Development and Cooperation through Asean, Geographical Review, Vol. 81, No. 1 (Jan., 1991), pp. 87-98, American

Geographical Society, p. 1

22

Bertrand Fort and Douglas Webber. “ Regional Integration in East Asia and Europe: Convergence or divergence?”, Routledge. 2006, p.151

23

Fort, p.151

24

Fort, p. 166

25

Fort, p69.

26

Higgott, p31.

27

Higgott, p29.

28

Hussey, p. 90

29

Tan, p.938

20

fuels. Increased trade is inhibited by the lack of complementarity between members, both in types of goods and market

characteristics, and prohibitive nontariff barriers

30

.

Before evaluating ASEAN’s effectiveness towards regional integration, it should be noted that it was originally intended

for economic development and was fiercely protective of sovereignty, so progress towards supranational institutions

remains limited. This history of ASEAN, the development of its membership and ad-hoc adjustments to policy,

characterize the critical regional organization and provided for an understanding of why and how regional integration, in

general, is progressing the manner and style it is.

Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS)

The Greater Mekong Sub-Region (GMS), which consist of Cambodia, the People's Republic of China (PRC, specifically

Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuangzu Autonomous Region), Lao People's Democratic Republic (Lao), Myanmar,

Thailand, and Viet Nam, is geographically located among the fast-growing economies of both South and East Asia. It has

a combined population of nearly 320 million—more than that of the United States of America—and a contiguous land

area of about 2.5 million square kilometers—roughly the size of Western Europe. The GMS is rich in human and natural

resources, and its people are bound by a shared culture and history

31

.

In 1992, the GMS Economic Cooperation Program (GMS Program) was launched with the support of Asian Development

Bank (ADB), setting out “to promote sustainable economic development through closer economic linkages between its

member states.

32

” As enunciated by the GMS leaders, the vision of the GMS Program is a sub-region that is prosperous,

integrated, and harmonious. This vision is embodied in the 3Cs strategy of enhanced Connectivity, increased

Competitiveness, and a greater sense of Community. The GMS Program seeks to enhance their economic relations,

building on their shared histories and cultures, covering nine priority sectors: agriculture, energy, environment, human

resource development, investment, telecommunications, tourism, transport infrastructure, and transport and trade

facilitation; moreover, GMS program planned to help the participating countries achieve the Millennium Development

Goals (MDGs) through “increasing connectivity, improving competitiveness, and engendering a greater sense of

community (the three Cs, ADB 1996).

In 2002, the GMS countries assembled the various sector approaches with their associated programs and projects into a

comprehensive strategic framework for sub-regional development with a focus on five strategic thrusts (strengthening

infrastructure linkages, facilitating cross-border trade and investment, and enhancing private sector participation,

developing human resources, as well as environmental protection) and 11 flagship programs, including the 3 economic

corridor (EC). Apart from hardware in the form of physical infrastructure, the GMS program has also tried to address

complementary software issues. A key initiative towards this end is the Cross-Border Transport Agreement, a

comprehensive multilateral instrument that supports a range of measures to facilitate trade and investment, which in

turn promotes integration.

“The formulation of the GMS–SF in 2002 took into account the global and regional trends relevant to economic

cooperation at that time, and these trends have continued and accelerated, bringing globalization and regional

integration to a higher level. The Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Cooperation between ASEAN and

the PRC was signed in November 2002, shortly after the 1st GMS summit, and one year later, similar framework

agreements were signed between ASEAN and the Republic of Korea (ROK), and between ASEAN and Japan. These

30

Tan, p. 936

31

ADB, “Midterm review of the GMS Strategic Framework (2002-2012)”, 2007, p2

32

` Bafoil and Ruiwen, 2010,p 80

21

developments show that the environment and context for GMS development have changed dramatically over the last

several years because of accelerating globalization and regional economic integration (REI)”

33

.

In doing so, the program has indeed accelerated, delivering concrete results and contributing to economic growth and

poverty reduction in the sub-region, as well as to the broader realization of a prosperous, integrated, and harmonious

GMS. The pragmatic, action-oriented, and results-focused approach of the Program enabled GMS countries to expedite

the implementation of high-priority sub-regional projects and initiatives. It also mobilized an increasing amount of

financial assistance from development partners and other important stakeholders. During the past 2 decades, Gross

domestic product (GDP) in the sub-region has grown at over 8% per year on average, which was one of the fastest rates

in the world; real per capita incomes have more than tripled during the same period, the poverty incidence in GMS

countries based on national poverty lines has declined substantially, and GMS countries have made major progress in

meeting the other Millennium Development Goals.

By the end of 2010, GMS loans (grants) had financed 55 projects with a total investment of 13.8 billion dollars, of which

5 billion dollars was ADB’s own lending $ 5 billion, GMS governments matching funds of $ 4.3 billion co-financing of $ 4.5

billion; technical assistance 172 projects totaling approximately $ 230 million, of which ADB’s own lending $ 100 million,

GMS governments to provide matching funds of $ 20 million co-financing of $ 110 million.

In light of these successes and looking ahead, GMS countries wish to maintain the overall Direction of the GMS Program.

The GMS Program begins its third decade in 2012. The new ten-year (2012-2022) strategic framework of the GMS

Economic Cooperation endorsed at the Fourth GMS Summit in Nay Tyi Taw on Dec. 20, 2011. The strategic framework

for 10 years of the GMS Program builds on the substantial progress the program has made and the likely future global

and regional trends, as well as on the commitment that member countries have made in their national development

plans to the promotion of regional integration and, to encouraging greater GMS integration as part of a broader process

of greater integration within ASEAN and the Asia region. The new strategic framework proposes eight priority sectors for

cooperation: namely GMS economic corridor development, infrastructure linkages, energy, telecommunications,

tourism, agriculture, environment and human resources development.

33

ADB, “Midterm review of the GMS Strategic Framework (2002-2012)”, 2007, p11

22

1.2 Four Pillars

Strategy

One of the pre-field-trip research tools employed by the capstone group was to examine what was driving the various

actors and institutions in the region and how their strategies manifested. In this case, strategies can be considered ‘the

science and art of employing the political, economic, psychological, and military forces of a nation or group of nations to

afford the maximum support to adopted policies’. It also speaks to the potential geo-politics in the region. At a lower

level, it was considered important to also look at the main groups of investors and their interests and impacts on

development in the area. Some of these actors have already been discussed earlier and their strategies will only briefly

be illuminated.

China: China’s involvement in the GMS has occurred through the inclusion of South-Western provinces Yunnan and

Guangxi in the development project. It has also been critically involved in the development of the North-South Corridor,

which stretches from Kunming to Bangkok and from Kunming to Hanoi, and has contributed about US$4billion in

highway construction. The priority of the GMS has shifted to become a national policy issue. Beijing has also promoted

trade and investment in GMS by unilaterally removing tariffs. Meanwhile, plans have also been announced to expand

development projects in the GMS – including into human resources, trade and investment facilitation and

telecommunications. In terms of the country’s FDI policy, decentralised authority has been encouraged, the

development of better regulation and the creation of ‘State Level Economic & Technological Development Zones’ and

border economic cooperation zones. Trade between China and the GMS countries consists of mostly mineral

commodities, forestry items, agricultural goods and resource-based products. However, China’s investment in the GMS

had been increasing steadily. More importantly is the PRC’s Future Plan which involves: improving cooperation between

Guangxi and ASEAN; turning Yunnan into an important bridgehead open to southwest; and, according to local 12

th

5 year

plans, improving the cooperation between provinces and ASEAN, GMS, and accelerating the construction of the

economic corridors.

Japan: Japan has had a long history with South East Asia and has maintained a presence there for critical periods of

growth when China's involvement had retracted. Japan was the key to the development of networks and chains and

encouraging the flow of trade in the region. The Japanese automobile industry began its overseas operations in 1960,

starting with operations in Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand. This initial start was due to the region's proximity to Japan

and a lack of local competitors

34

. However, its presence initially was mainly to serve local markets and maintain a

presence. The electronics industry took a greater interest in South East Asia in the 70s due to the appreciation of the

yen, and moved its labour-intensive processes to the region. These were generally concerned with low-end products. In

Thailand, it meant an important role of the Eastern Seaboard industrial area which is significant today.

Investors: Recent figures from Thailand’s Board of Investment indicate that Japan remained the largest foreign investor

in Thailand, with 101 projects and a combined investment value of Bt38.253 billion. In second place was the United

States, with 10 projects and Bt8.162 billion in investment value. Japan has been a significant investor in Thailand despite

China’s increasing presence. This is clear through statistics provided by BOI, however the more subtle details of their

different impacts on development through investment are the work of the case studies. However, foreign investment

into Cambodia has been much more dominated by China. Various sources say China is the main investor into Cambodia

and has maintained that status for about 14 years with nearly $6bn

35

. South Korea followed with nearly $3bn and