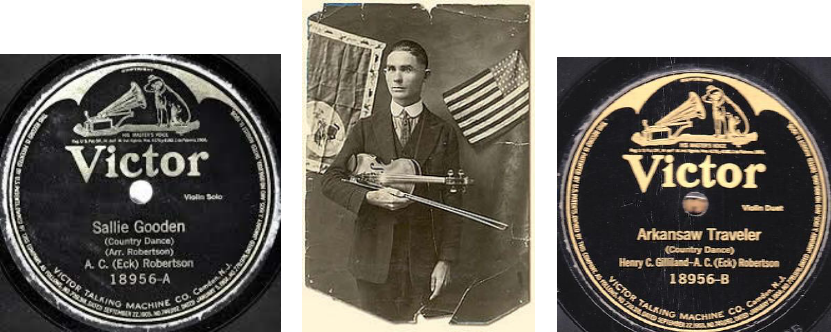

“Arkansaw Traveler” and “Sallie Gooden”--Eck

Robertson (1922)

Added to the National Registry: 2002

Essay by Wayne Erbsen (guest post)*

“Sallie Gooden” label Eck Robinson “Arkansaw Traveler” label

Eck Robertson - Cowboy Fiddler

In 1877, Thomas Edison invented the photograph. By the next year he established the Edison Speaking

Phonograph Company to sell record players in furniture stores across America. Improvements by such

inventors as Alexander Graham Bell and Emile Berliner helped to make “gramophones” coveted items

for home entertainment. Sales of records went to four million units in 1900, up to 30 million in 1909,

and over 100 million by 1920. By 1922 alone, consumers could purchase such hit records as “Way

Down Yonder in New Orleans,” “Carolina in the Morning,” “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister

Kate” and “Somebody Stole My Gal.”

But people who liked their music on the rustic side found it impossible to purchase phonograph records

of old-time fiddling or stringband music in the early years of the twentieth century. This was because

in those days record companies were mainly located in New York City, and they simply did not realize

there was a market for the music of rural America. All this changed in 1922, when into the New York

City offices of RCA records walked Eck Robertson and Henry Gilliland. But wait, we’re getting ahead

of ourselves.

The story actually begins in the late 1880s when Alexander Campbell “Eck” Robertson was growing

up in north central Texas. Every one of his five brothers and two sisters played music and sang. Both

of his grandfathers, as well as his uncles and his father, actively competed at local and regional fiddlers

conventions in the late 19

th

and early 20

th

century. Eck later claimed that he taught himself to play the

fiddle before he ever saw one. As a kid he killed a tomcat, tanned its hide and stretched the skin over a

long-necked gourd to make himself a home-made gourd fiddle. One of his brothers traded a pig for a

genuine factory-made fiddle, and Eck was soon playing that. Eck later recounted his innate ability to

play tunes on the fiddle. He said, “It was just natural with me to play them. I didn’t have to learn

them.... I already knew them. I mostly improved every old hoedown tune that was ever put out. I

generally played better than anyone else, [and had] better arrangements of the tunes.”

In 1903, 16 year-old Eck decided then and there to become a professional musician. He soon left home

and joined a traveling medicine show. Over the next several years he worked with a half-dozen

different medicine shows. In 1906, Eck got married and he and his new wife, Netty, started out

traveling around Texas and adjacent states, playing fiddle and piano in silent-movie houses. Never shy

about promoting himself, Eck was a superb showman who billed himself as “The Cowboy Fiddler” and

outfitted himself from head to toe in the style of a western cowpuncher. When interviewed in the mid-

1960s, Eck remembered that, “I was the most popular dang fiddler ever was on the road. I could book

every dang town I came to, it didn’t make any difference where it was. There were lots of places where

they turned musicians down, but I came right along and booked them.”

After Eck had honed his fiddle chops to a fine edge, he started winning the fiddler’s conventions that

were held all over the southwest. Competition at these fiddle contests was notoriously fierce, and

winning was no mean trick. One story has Eck in a showdown playoff with John Wills, the father of

legendary fiddler Bob Wills. In a last-ditch effort to give himself an edge, legend has it that Eck broke

off a piece of a wooden match and stuck it under one of his strings, so that he could bow three strings at

once. The trick worked and Eck was victorious.

At another popular fiddlers convention held in Munday, Texas, John Wills and Eck were running neck

and neck, so the judges decided that the pair should play a run-off. This was a prestigious convention

and a lot of prize money was at stake. Eck was up first and he likely played “Beaumont Rag,” one of

the numbers he often performed when the competition was stiff. John Wills got up next and played

“Gone Indian,” which was his lucky tune that had helped him win many fiddle competitions. When

John reached a certain point in the tune, he let out a high-pitched cry that he held for what seemed like

several minutes. Of course, when he finished fiddling, the audience went wild and the judges awarded

him first prize. When Eck was leaving the festival grounds someone hollered out to him, “Eck, did

John out-fiddle you?”

Eck shot right back with “Hell, no! He didn’t out-fiddle me. That damned old man Wills out-hollered

me.”

In addition to competing at fiddlers conventions, by 1919 Eck started attending reunions of

Confederate veterans. In June of 1922, Eck traveled to a Confederate reunion in Richmond, Virginia.

It was perhaps there that he met, or was reacquainted with, 76-year-old Henry Gilliland (1845–1924),

who had fought in the Civil War and was later an Indian fighter and Justice of the Peace. Somehow, the

pair decided to travel to New York to try to convince RCA Victor to let them make records. They were

apparently undaunted by the fact that no record company had ever shown the slightest interest in

recording old-time fiddle music.

Part of the reason that Eck and Henry decided to make the trip to New York was that Henry was

acquainted with a lawyer named Martin W. Littleton, who did occasional legal work for the RCA

Victor label. He invited the musicians to stay with him after they arrived in New York and promised to

introduce them to the people at the office of Victor records. And that’s exactly what happened.

The staff at Victor must have been flabbergasted when Eck and Henry showed up unannounced at their

Manhattan office, with Robertson and Gilliland both dressed head-to-toe in full cowboy regalia. Trying

to dispatch the pair with impunity, one of the Victor officials bustled into the waiting room and said to

Eck, “Young man, get your fiddle out and start off a tune.” Eck responded by breaking into a rousing

version of “Sallie Gooden,” a tune he had used to win many a fiddle contest in Texas.

He later recalled that, “I didn’t get to play half of ‘Sallie Gooden,’ he just threw up his hands and

stopped me. He said, ‘By Ned, that’s fine! Come back in the morning at 9:00 o’clock and we’ll make

a test record.”

The next day, June 30, 1922, Eck and Henry returned and recorded “Arkansas Traveler,” “Turkey in the

Straw,” “Forked Deer” and “Apple Blossom.” Eck alone returned the next day and recorded “Sallie

Gooden” and several other tunes. With the September 1, 1922 release of “Sallie Gooden,” Eck and

Henry had truly broken new ground. The release marked the initial foray into country music by a

reluctant record company. In retrospect, Eck’s performance of “Sallie Gooden” justly deserves credit

for being not only one of the first recordings in country music, but also one of the very best. Even

today, some 90-plus years later, few fiddlers have come up to the level of Eck’s fiddling. Bill Monroe

himself paid homage to Eck’s skill when he rushed ace Oklahoma fiddler Byron Berline into the studio

in 1967 and recorded “Sally Goodin.” Himself a renowned contest fiddler, Byron showed his own debt

to Eck by basically playing a slightly souped-up rendition of the original 1922 version of the tune.

Even today, virtually every fiddler who plays this standard fiddle piece in some way owes a debt to Eck

Robertson. But even more than his influence on the tune itself, Eck set an extremely high standard that

fiddlers ever since have tried to follow.

The stories behind “Sallie Gooden” are almost as good as the tune itself. Eck Robertson later

recalled that, “Long ago there lived a beautiful maiden. She sent word to all the lands around about for

fiddlers to come together and have a big fiddlers contest. And to the one who played the tune that

suited her the best, she'd give her heart and hand. One young man won the contest, his name was

Gooden. And the tune thereafter was called ‘Sallie Gooden.’”

Byron Berline once told his own version of this same story behind “Sallie Gooden.” He said:

Once upon a time there lived a girl named Sally who had two boyfriends. The two boys were both

fiddle players, and one of the boys had the last name of “Goodin.” Sally couldn't decide which one

to marry, so she thought a fiddle contest between the two would be a good way to make her

selection. Of course, the fellow named Goodin won the contest, and Sally became Sally Goodin.

They were very happy and had a productive life with 14 children, so I'm going to play “Sally

Goodin” 14 different ways.

The North Carolina musician Bruce Green collected a different story about “Sally Gooden” from

Hiram Stamper, a fiddler from Knott County, Kentucky. Hiram was born in 1893 and learned to play

from several Civil War veterans, who told him the story behind “Sallie Gooden.” According to him,

the tune originally had several names, including “Boatin’ Up Sandy” and “The Old Bell Ewe And The

Little Speckled Wether.” The name was changed during the Civil War by several soldiers who were

attached to John Hunt Morgan’s unit of irregulars. Apparently the company set up camp on the Big

Sandy River in Pike County, Kentucky. Nearby was a boarding house that was run by a kind-hearted

woman named Sally Gooden. She went out of her way to be kind to the soldiers by allowing them to

camp and play their fiddles on her property. In appreciation of her hospitality, the solders renamed the

tune “Sallie Gooden” in her honor.

Even though the origin of the name of “Sallie Gooden” may be hotly debated, one thing is crystal clear:

the powerful way that Eck Robertson fiddled it on Victor Records in 1922 will endure for all time.