54

ECB

Monthly Bulletin

December 2014

Box 3

INDIRECT EFFECTS OF OIL PRICE DEVELOPMENTS

ON EURO AREA INFLATION

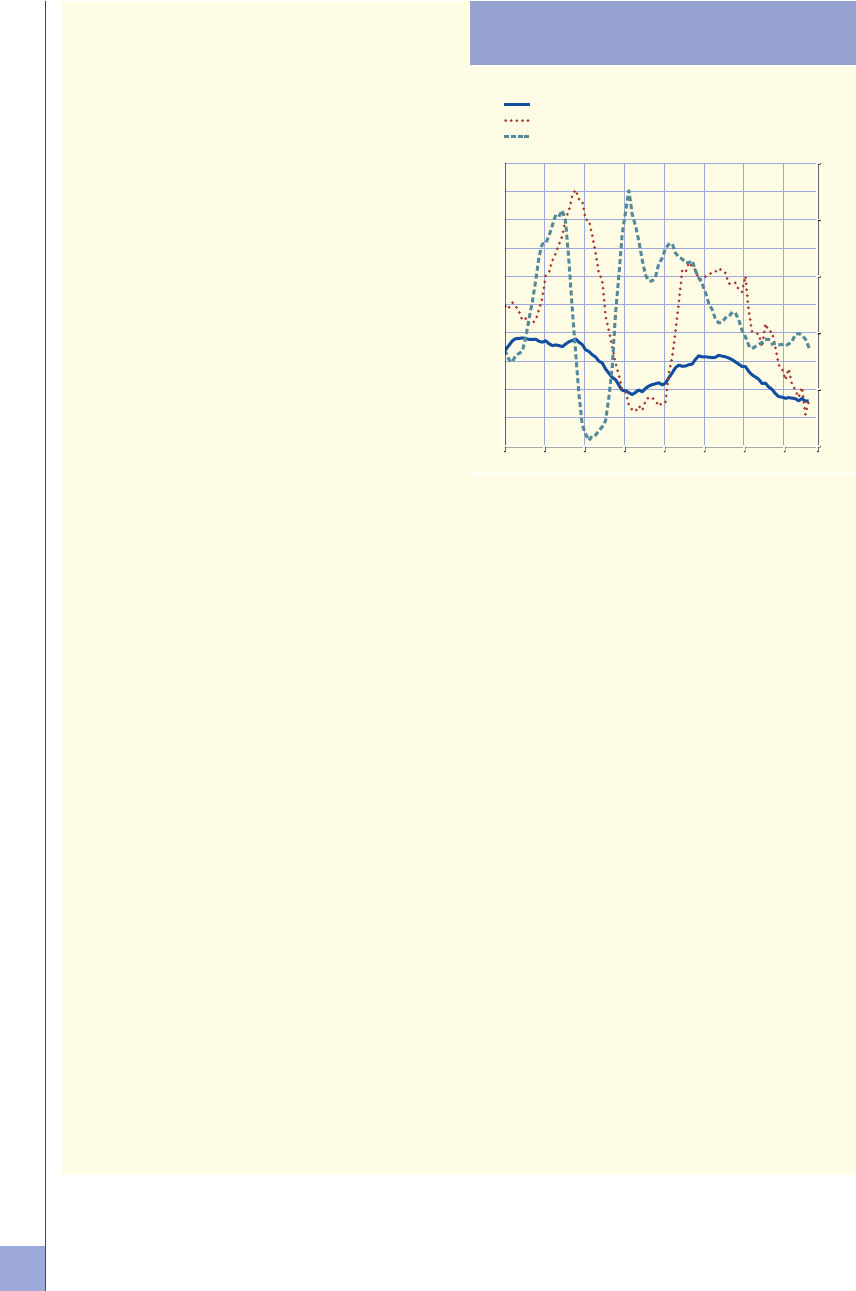

Having risen sharply from early 2009 to 2011,

oil prices hovered around a broadly stable

level of USD 110 per barrel from early 2012 to

mid-2014. Owing to the appreciation of the

euro against the dollar, oil prices in euro

terms edged downward over that period. Since

mid-2014 oil prices have declined markedly,

standing around USD 70 per barrel in late

November, with the decline in the USD/EUR

exchange rate to some extent attenuating the

impact in euro terms (see Chart A).

Via the energy component of the HICP, the

evolution of oil prices has accounted for a

noteworthy part of the decline in headline

HICP inflation since late 2011.

1

Initially,

this reflected base effects as the upward impact of earlier oil price increases dropped out of the

annual comparison. Subsequently, it reflected the gradual decline in oil prices in euro terms.

However, the developments in oil prices are also likely to have had a more general impact on the

non-energy components of the HICP. This box recalls the indirect effects of oil price

developments on HICP inflation excluding energy and food.

The notion of indirect effects

In contrast to the direct effects on HICP inflation that changes in oil prices have via their effect on

consumer energy prices, indirect effects refer to the impact of changes in oil prices via production

costs. Such indirect effects are rather obvious in the case of some transportation services, such

as aviation, where fuels are a major cost factor. However, they are also likely to be present in

the case of consumer goods and services that are produced with relatively high oil and, more

generally, energy intensity, such as some pharmaceutical products and some materials used for

household maintenance and repair. Moreover, given the important role of imports as inputs in

domestic production processes or as final consumption goods, changes in oil prices may also have

indirect effects on euro area inflation if they trigger changes in output prices in the economies

of the trading partners. Chart B shows the broad co-movement between oil prices and producer

prices. Both producer prices of the trading partners of the euro area, which shape euro area import

prices, and producer prices of euro area producers for the domestic economy tend to follow oil

price developments with some lag.

Gauging the quantitative role of indirect effects

By their very nature, indirect effects on consumer price inflation are difficult to pin down in the data

and their quantification is surrounded by a degree of uncertainty. This is due to their more drawn

1 For a more detailed discussion, see the box entitled “The role of global factors in recent developments in euro area inflation”, Monthly

Bulletin, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, June 2014.

Chart A Evolution of oil prices and the

USD/EUR exchange rate

(EUR; USD; daily data)

1.20

1.25

1.30

1.35

1.40

1.45

1.50

1.55

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

brent crude oil (USD/barrel; left-hand scale)

brent crude oil (EUR/barrel; left-hand scale)

USD/EUR exchange rate (right-hand scale)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

55

ECB

Monthly Bulletin

December 2014

Prices

and costs

Economic

and monEtary

dEvElopmEnts

out nature, as well as the fact that oil or oil-related input costs are only one factor in firms’ pricing

decisions and that other issues such as strategic considerations vis-à-vis competitors or the cyclical

position of the economy may play a role. The uncertainty is also compounded by the possibility

that the indirect effects of oil prices may be blurred by offsetting or enhancing factors such as

developments in exchange rates or world economic growth.

According to a study conducted by

Eurosystem staff in 2010 and based on

macroeconomic models, at the currently

observed oil price levels of USD 60-80 per

barrel, approximately two-thirds of the impact

of oil prices on consumer price inflation

would stem from direct effects on HICP

energy component, while around one-third

would be due to the effects on HICP inflation

excluding energy.

2

More specifically, a 10%

change in oil prices was estimated to give rise

to a 0.4 percentage point impact via direct

effects on the energy component – most of

which would happen relatively quickly – and

an approximate 0.2 percentage point impact

via other HICP components over a period of

up to three years.

2 See the article entitled “Oil prices – their determinants and impact on euro area inflation and the macroeconomy”, Monthly Bulletin,

ECB, Frankfurt am Main, August 2010. Given the important role played by excise taxes in energy inflation, the impact of a given

change in oil prices on energy inflation is higher if the price of oil increases. Higher (lower) oil prices thus tend to heighten (reduce) the

relative importance of direct effects in the overall impact. Three complementary approaches were used to estimate the impact of indirect

and second-round effects: (i) input-output table analysis, (ii) a structural vector autoregressive (VAR) model, and (iii) macroeconomic

models employed by the Eurosystem. In practice, it was difficult to disentangle the indirect effects from the second-round effects, but

the impact of the second-round effects seemed to have attenuated over time, most likely reflecting changes in wage-setting behaviour

(less automatic indexation of wages) and the anchoring of inflation expectations through monetary policy.

Chart C Estimated impact of crude oil price

developments on HICP inflation excluding

food and energy

(annual percentage changes and contributions; quarterly data)

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

-0.2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2011 2012 2013 2014

impact from other factors

estimated impact of oil prices

HICP excluding energy and food

Source: ECB calculations based on Eurosystem macroeconomic

models – see footnote 2.

Chart B Evolution of oil prices and producer prices

(annual percentage changes; monthly data)

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

-9

-6

-3

0

3

6

9

12

15

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

producer price index for euro area trading partners

1)

brent crude oil (USD/barrel; right-hand scale)

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

-9

-6

-3

0

3

6

9

12

15

producer price index for the euro area

brent crude oil (EUR/barrel; right-hand scale)

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Sources: Bloomberg, Eurostat, OECD and ECB calculations.

1) As implied by the real effective exchange rate of the euro (nominal exchange rate vis-à-vis 20 trading partners deflated by relative producer prices).

56

ECB

Monthly Bulletin

December 2014

In this context, a counterfactual exercise

based on such elasticities suggests

that oil prices have accounted for

approximately 0.6 percentage point of

the 0.9 percentage point decline in HICP

inflation excluding energy and food since

the end of 2011 (see Chart C). This mostly

reflects the unwinding of the upward impact

associated with the rise in oil prices up to that

point in time. As the impact in this exercise is

estimated on the basis of the HICP excluding

food and energy, it excludes the direct effects

on the energy component.

A more data-oriented way to gauge the

presence of indirect effects is to focus on

those items of the HICP excluding energy and

food that are more likely to be affected by oil

price developments. From the available set of

items, these are selected by means of simple

regressions of quarter-on-quarter changes in

the individual HICP item on an autoregressive

term and relevant lags of changes in oil prices. Chart D shows the evolution of the HICP

aggregate comprising the items for which significant lagged oil price impacts were found.

3

These

items have a weight of approximately 10% in the HICP excluding energy and food. However,

given their greater amplitude, they have contributed around 25% to the decline in HICP inflation

excluding energy and food over the past two years.

Overall, in addition to the fairly significant and immediately visible direct downward effects of

the recent oil price declines on the energy component of the HICP, it is reasonable to also expect

downward impacts on other HICP components via indirect effects. The precise magnitude and

timing of these effects is generally uncertain. Like direct effects, however, indirect effects on

the annual rate of change in prices should, in principle, be temporary, and related to the period

of adjustment to the change in oil prices. Therefore, they should not influence inflation on a

sustained basis. Nevertheless, it is important that such temporary developments do not feed

into longer-term inflation expectations and do not have a more lasting impact on wage and

price-setting behaviour via second-round effects.

3 From the non-energy industrial goods component, these selected items include (i) Non-durable household goods (056100), (ii)

Materials for the maintenance and repair of the dwelling (043100), (iii) Pets and related products (0934_5), (iv) Spare parts and

accessories for personal transport equipment (072100) and (v) Clothing materials (031100). From the services component, they

include mainly transport-related services, in particular (i) Other purchased transport services (073600), (ii) Passenger transport by

road (073200), (iii) Other services relating to the dwelling n.e.c. (044400), (iv) Passenger transport by sea and inland waterway

(073400), (v) Passenger transport by air (073300), and (vi) Package holidays (096000). These items were chosen on the basis of

their link with oil price movements. A relatively simple (and partial) autoregressive distributed lag model was estimated for

each of the 93 detailed HICP subcomponents i in each of the euro area countries c over the sample period from 2000 to 2014,

):,(

41,,,,

qoq

t

qoq

t

qoq

tci

qoq

tci

OILOILHICPfHICP

--

=

, where HICP denotes the quarter-on-quarter rate of change in the seasonally-adjusted HICP

component i in country c at time t, and OIL denotes the quarter-on-quarter rate of change in oil prices (in euro terms) at time t. Owing

to co-movements among commodity prices, it may be that this methodology also captures impacts from other commodity prices such

as food and industrial raw materials.

Chart D Evolution of oil prices, HICP

excluding food and energy and selected

HICP components

(annual percentage changes; monthly data)

-50

-25

0

25

50

75

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

HICP excluding energy and food

selected HICP items

1)

brent crude oil (EUR/barrel; right-hand scale)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

1) These HICP components have a high sensitivity to oil price

movements. See footnote 3 for a more detailed explanation.