1

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

11

The UK immunisation schedule

The routine immunisation schedule

The overall aim of the routine immunisation schedule is to provide protection against the

following vaccine-preventable infections:

●

diphtheria

●

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

●

hepatitis B

●

human papillomavirus (certain serotypes)

●

influenza

●

measles

●

meningococcal disease (certain serogroups)

●

mumps

●

pertussis (whooping cough)

●

pneumococcal disease (certain serotypes)

●

polio

●

rotavirus

●

rubella

●

shingles

●

tetanus

The schedule for routine immunisations and instructions for how they should be

administered are given in Table 11.1. The relevant chapters on each of these vaccine-

preventable diseases provide detailed information about the vaccines and the immunisation

programmes.

2

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

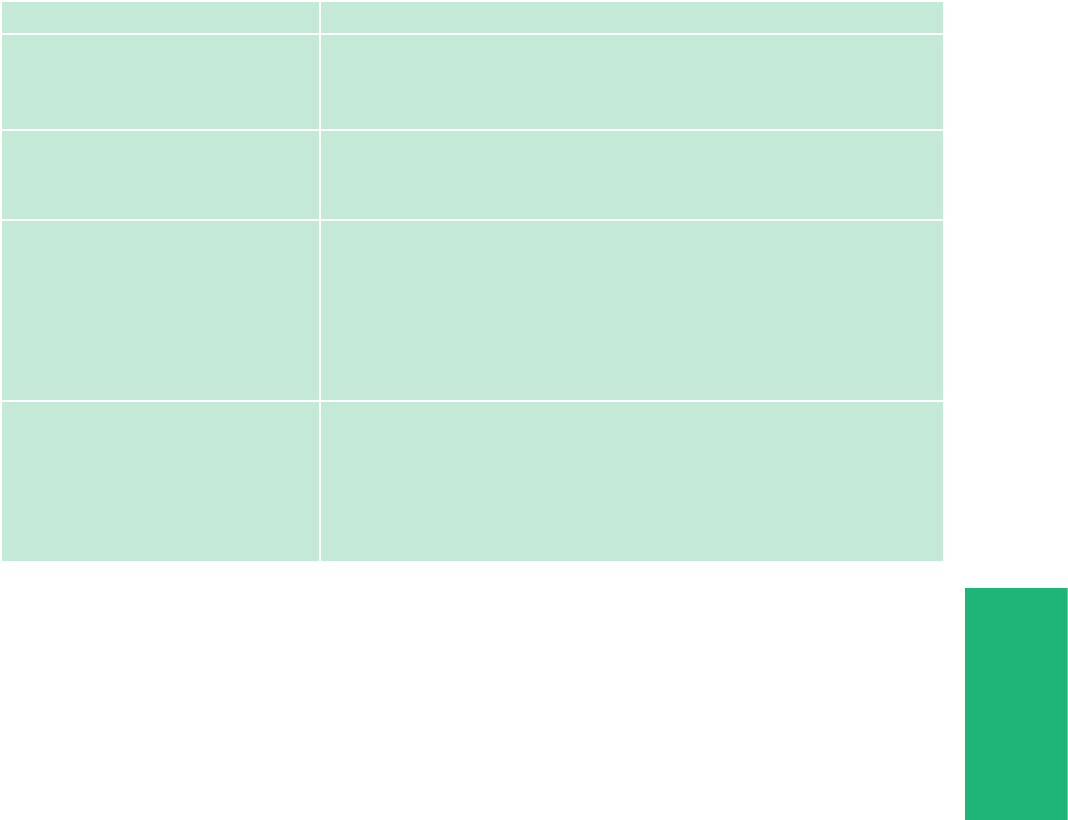

Table 11.1 Schedule for the UK’s routine immunisation programme (excluding catch-

up campaigns)

Age due Vaccine given

How it is given

1

Eight weeks old Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio,

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and

hepatitis B (DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB)

Meningococcal B (MenB)

Rotavirus

One injection

One injection

One oral application

Twelve weeks old Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, Hib

and hepatitis B (DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB)

Rotavirus

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13)

One injection

One oral application

One injection

Sixteen weeks old Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, Hib

and hepatitis B (DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB)

Meningococcal B (MenB)

One injection

One injection

One year old (on or

after the child’s first

birthday)

Hib/MenC

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13)

Meningococcal B (MenB)

Measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)

One injection

2

One injection

2

One injection

2

One injection

2

Eligible paediatric

age groups

Chapter 19)

Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) Nasal spray, single application

in each nostril

(if LAIV is contraindicated and

child is in a clinical risk group,

give inactivated flu vaccine;

see Chapter 19)

Three years four

months old or soon

after

Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio

(dTaP/IPV)

Measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)

One injection

One injection

Twelve to thirteen

years old

Human papillomavirus (HPV) Course of two injections at

least six months apart

Fourteen years old

(school year 9)

Tetanus, diphtheria and polio (Td/IPV)

Meningococcal ACWY conjugate

(MenACWY)

One injection

One injection

65 years old Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) One injection

65 years of age and

older

Inactivated influenza vaccine One injection annually

70 years old Shingles vaccine One injection (live vaccine)

Two injections (inactivated

vaccine)

1 Where two or more injections are required at the same time, these should ideally be given in different

limbs. Where this is not possible, injections in the same limb should be given at least 2.5cm apart.

2 Where injections can only be given in two limbs, it is recommended that the MMR, as the vaccine least

likely to cause local reactions, is given in the same limb as the MenB with the PCV13 and Hib/MenC doses

given into the other limb.

3

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

The childhood immunisation schedule has been designed to provide early protection

against infections that are most dangerous for the very young. This is particularly important

for diseases such as whooping cough, rotavirus and those due to pneumococcal, Hib and

meningococcal infections. Providing subsequent booster doses as scheduled should ensure

continued protection. Further vaccinations are offered throughout life to provide protection

against infections when eligible individuals reach an age where they can derive most

benefit (such as because of an increased individual risk) or where the programme will

provide optimal control of that disease for the whole population.

Recommendations for the age at which vaccines should be administered are informed by

the age-specific risk for a disease, the risk of disease complications, the ability to respond

to the vaccine and the impact on spread in the population. The schedule should therefore

be followed as closely as possible.

Some individuals may be eligible for additional vaccines due to an underlying medical

condition or circumstances that put them at increased risk of catching a vaccine-

preventable disease or of complications from that disease. These individuals should be

vaccinated in accordance with the recommendations in Chapter 7 and the disease specific

chapters.

Seasonal influenza

Those eligible for influenza vaccine (on the basis of age or clinical risk) should be

vaccinated each winter, usually between October and January, although vaccination may

still be of some benefit if given later. The annual letters on the influenza programme

should be consulted for age eligibility:

England: www.gov.uk/government/collections/annual-flu-programme

Northern Ireland: www.health-ni.gov.uk/topics/professional-medical-and- environmental-

health-advice/hssmd-letters-and-urgent-communications

Scotland:www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/index.asp

Wales: gweddill.gov.wales/topics/health/nhswales/circulars/public-health/?lang=en

4

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

Schedule flexibility

The schedule recommended by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation

(JCVI) incorporates the minimum intervals between subsequent doses of the same vaccine.

As immunological memory from priming dose(s) are likely to be maintained in healthy

individuals, increasing that interval will usually lead to a more pronounced response to the

later dose. Therefore, where any course of immunisation is interrupted, there is

normally no need to start the course again - it should simply be resumed and

completed as soon as possible. Where vaccination was commenced some time

previously however, the product received, or the eligibility may have changed, and the

relevant chapter should therefore be consulted.

Immunisations should not be given before the scheduled age unless there is a clear clinical

indication for this. The first set of primary immunisations can be given from six weeks of

age if required in certain circumstances such as travel to an endemic country. Administering

the first set of primary immunisations before 6 weeks of age is not recommended, as it

may result in a sub-optimal response to the vaccine which could undermine good control.

MMR vaccine can be given from six months of age, for example during a local outbreak or

if travelling to a high incidence country. Any dose of MMR given below the age of one

year should be discounted as residual maternal antibodies may reduce the response to the

vaccine. Two further doses of MMR will therefore be required at the appropriate ages.

Delaying primary infant immunisations beyond eight weeks risks leaving babies

unprotected against serious infections that can be very severe in the very young, such as

whooping cough. The six to eight week baby check is not required as part of the

assessment for immunisation, and so the eight week primary immunisations should never

be delayed because of any delay in carrying out this examination.

Every effort should be made to ensure that all children and adults are immunised, even if

they are older than the scheduled age; no opportunity to immunise should be missed. The

type of vaccine and number of doses recommended depends on the age of the individual

as some vaccines are not indicated after a certain age. In most instances, this is because

the ability to benefit from vaccination is reduced because of lower risk (e.g. whooping

cough), or lower effectiveness (e.g. for shingles). The exception is rotavirus vaccine, where

vaccination at an older age is more likely to be associated with an adverse event

(intussusception) (see Chapter 27b: Rotavirus for more information).

Recording of immunisation

Following immunisation, all the patient’s clinical records including the GP held record and,

if a child, the record on the Child Health Information System (CHIS) and the Personal Child

Health Record (Red Book) should be updated with all the relevant details (see Chapter 4).

When babies are immunised in special care units, or children and adolescents are

immunised opportunistically in accident and emergency units or inpatient facilities, it is

important that a record of the immunisation is entered onto the relevant CHIS and sent to

the patient’s GP for entry onto the practice-held patient record. Details should also be

recorded in the child’s Personal Child Health Record (Red Book) in a timely manner. Details

of vaccines given in other areas, such as schools/maternity services/pharmacies, should also

be sent to the patient’s GP.

5

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

Where possible, records of immunisation should be requested from children and adults

arriving from overseas and entered onto the GP held record and other clinical records as

appropriate. This will avoid the individual being flagged for vaccination and provide

reassurance during local outbreaks.

A toolkit with information on the vaccines used in several other countries can be

downloaded to facilitate accurate coding at the following:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-and-international-immunisation-schedules-

comparison-tool

Childhood immunisation programme

When children attend for any vaccination, it is important to also check that they are up-to-

date for any vaccines that they should have received previously. The table below gives an

example checklist at each key stage; doses of those vaccines that have not been received

but are still indicated at that age should be caught up. Catch-up doses should be

administered as soon as possible but leaving the appropriate intervals as advised in the

relevant chapters.

At a minimum, children’s immunisation status should be checked at these key ages, see

Table 11.2, and the child offered catch-up for any missing vaccinations.

Table 11.2 Routine immunisation schedule vaccination history at key ages

Key age Vaccines child should have had or catch-up with

At the age of

12 months:

Three doses of diphtheria, tetanus, polio, pertussis, Hib and hepatitis B containing

vaccine.

A single dose of PCV vaccine.

Two doses of MenB vaccine.

At the age of

24 months:

Three doses of diphtheria, tetanus, polio, pertussis (and hepatitis B) containing

vaccines.

A single dose of Hib/MenC and PCV13 vaccines after the age of one year.

Either 2 doses of MenB under the age of one and one dose after the age of one

year; or 2 doses of MenB after the age of one year.

A single dose of MMR vaccine after the age of one year.

At school

entry:

Four doses of diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and polio containing vaccine.

Two doses of MMR vaccine after the age of one year.

A single dose of Hib/MenC conjugate vaccine after the age of one year.

At transfer to

secondary

school:

Four doses of diphtheria, tetanus and polio containing vaccine.

Two doses of MMR vaccine after the age of one year.

A single dose of Hib/MenC conjugate vaccine after the age of one year.

Before

leaving

school:

Five doses of diphtheria, tetanus, polio containing vaccine.

A single dose of MenACWY vaccine after the age of 10 years.

Two doses of MMR vaccine.

Two doses of HPV vaccine (at least 6 months apart)

1

1 All Females remain eligible for HPV vaccine up to their twenty-fifth birthday. All males born on/

after 1 September 2006 are eligible up to their twenty-fifth birthday

6

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

Adult immunisation programme

Five doses of diphtheria, tetanus and polio vaccines at the appropriate interval should

ensure long-term protection through adulthood (although additional doses may be

indicated for travel or following potential exposure to infection). Individuals who have not

completed the five doses should have their remaining doses at the appropriate intervals.

Where there is an unclear history of vaccination, adults should be assumed to be

unimmunised. A full course of diphtheria, tetanus and polio vaccine should be offered to

individuals of any age in line with advice contained in the relevant chapters. It is never too

late in life to start a course of vaccination.

Measles, mumps and rubella vaccine should be offered to all young adults who have not

received two doses as outlined in Chapter 21, Chapter 23 and Chapter 28. In particular,

vaccine status should be checked for all women of child-bearing age who should be

offered MMR to prevent rubella in pregnancy. In addition, up to the age of 25 years,

MenACWY vaccine should be offered to individuals who have never received a MenC-

containing vaccine (see Chapter 22) and HPV should be offered to eligible unvaccinated

individuals (see Chapter 18a for eligibility).

Older adults (65 years and older) should routinely be offered a single dose of

pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine if they have not previously received it. Annual

influenza vaccination should be offered from 65 years of age. Adults aged 70 years

become eligible for shingles vaccine and remain eligible until their 80th birthday. More

information on shingles vaccine eligibility is available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/

collections/shingles- vaccination-programme

Vaccination of individuals with unknown or incomplete immunisation status

For a variety of reasons, some individuals may present not having received some or all their

immunisations or may have an unknown immunisation history. Where an individual born in

the UK presents with an inadequate immunisation history, every effort should be made to

clarify what immunisations they may have had. Anyone who has not completed the

routine immunisation programme as appropriate for their age should have the outstanding

doses as described in the relevant chapters.

If children and adults coming to the UK do not have a documented or reliable verbal

history of immunisation, they should be assumed to be unimmunised and a full course of

required immunisations should be planned.

Individuals coming from areas of conflict or from population groups who may have been

marginalised in their country of origin (such as refugees, gypsy or other nomadic travellers)

may not have had good access to immunisation services. In particular, older children and

adults may also have been raised during periods before immunisation services were well

developed or when vaccine quality was sub-optimal. Where there is no reliable history of

previous immunisation, it should be assumed that any undocumented doses are missing

and the UK catch-up recommendations for that age should be followed.

An algorithm for vaccinating individuals with uncertain or incomplete immunisation status

is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaccination-of-individuals-with-

uncertain-or-incomplete-immunisation-status

7

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

Individuals coming to the UK who have a history of completing immunisation in their

country of origin may not have been offered protection against all the antigens currently

offered in the UK. Most countries have offered protection against diphtheria, tetanus, polio

and whooping cough for many years, but do not currently include MenC or MenB in the

schedule and may have introduced PCV and Hib vaccine relatively recently. Many countries

worldwide only offer single measles vaccines, rather than MMR, or have only recently

started to offer a rubella containing vaccine. Measles vaccine is also given below the age

of one year in many lower income countries. Doses of measles-containing vaccine given

below the age of one should be discounted and two further doses of MMR vaccine given

to ensure adequate protection against both measles and rubella.

Current country-specific schedules are available on the WHO website (http://apps.who.int/

immunization_monitoring/globalsummary).

Children coming to the UK may have received a fourth dose of a diphtheria/tetanus/

pertussis-containing vaccine that is given at around 18 months in many countries. Booster

doses given before three years of age should be discounted, as they may not provide

continued satisfactory protection until the time of the teenage booster. The routine pre-

school and subsequent boosters should be given according to the UK schedule.

Premature infants

It is

important that premature infants have their immunisations at the appropriate

chronological age (counted from their date of birth), in accordance with the national

routine immunisation schedule. As the benefit of vaccination is high in this group of

infants, vaccination should not be withheld or delayed.

As the occurrence of apnoea following vaccination is especially increased in infants who

were born very prematurely, specific guidance on the immunisation of premature infants in

Chapter 7 and the disease specific chapters should be followed.

Selective immunisation programmes

There are a number of selective immunisation programmes that target children and adults

at particular risk of serious complications from certain infections, such as hepatitis B,

hepatitis A, influenza, Hib, meningococcal and pneumococcal infection. Other vaccines,

including BCG, HPV, hepatitis B and hepatitis A, are also recommended for individuals at

higher risk of exposure to infection, due to lifestyle factors, close contact or recent

outbreaks in their community.

Individuals at risk of exposure through their work should be advised about any required

vaccinations by their employer or their occupational health service (Chapter 12). For more

information, please see Chapter 7 and the disease specific chapters.

Vaccination during and after pregnancy

In 2010, routine influenza immunisation of individuals was extended to include all

pregnant women. This was based on evidence of the increased risk from influenza to the

8

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

mother and to infants in the first few months of life. Vaccination therefore protects the

woman herself and provides passive immunity to the infant following birth. Preventing

infection in the mother will also reduce the risk of her transmitting influenza to her

newborn baby. Inactivated influenza vaccine should therefore be offered to pregnant

women at any stage of pregnancy (first, second or third trimesters), ideally before influenza

viruses start to circulate. Influenza vaccination is usually carried out between October and

January, but clinical judgement should be used to assess whether a pregnant woman

should be vaccinated after this period. The current level and severity of influenza activity,

the presence of other risk factors and the availability of inactivated influenza vaccine may

form part of the consideration for late vaccination.

A programme for the vaccination of pregnant women against pertussis was introduced in

October 2012. The purpose of the programme is to boost antibodies in these women so

that high levels of passive antibody are transferred from mother to baby. This should

protect the infant against pertussis infection until they can be vaccinated at eight weeks of

age. Pregnant women should be offered dTaP/IPV vaccine from week 16 of each pregnancy

(for operational reasons, vaccination is probably best offered at, or after the foetal anomaly

scan at around 20 weeks). This programme is described in more detail in Chapter 24.

Influenza vaccine can be given at the same time as pertussis vaccine, but influenza

vaccination should not be delayed in order to administer the two vaccines together.

Inactivated influenza vaccines are preferred to the live attenuated vaccine for pregnant

women (see Chapter 19). Pertussis vaccine can be given at the same time as influenza

vaccine but, to avoid compromising the passive protection to the infant, this should not be

used as a reason to give pertussis vaccination outside of the recommended period.

From 2016, the routine antenatal testing of women for rubella susceptibility ceased.

Pregnant women should have their vaccine status checked during or after pregnancy, for

example at the post-natal check, and be offered any outstanding doses of MMR soon after

delivery. MMR vaccine should not be offered in pregnancy.

Intervals between vaccines

Doses of different inactivated vaccines can be administered at any time before, after, or at

the same time as each other. Doses of inactivated vaccines can also be given at any interval

before, after, or at the same time as a live vaccine and vice versa.

A minimum four-week interval is normally recommended between successive doses of the

same vaccine - for example between each of the three doses of DTaP-containing vaccine in

the primary schedule. A better response is made to some vaccines when an eight-week

interval is observed between infant doses. Although shorter intervals may be advised to

achieve more rapid protection, e.g. for travel or during an outbreak, this may lead to a lower

immune response, particularly in infants, and may therefore provide less durable protection. If

one of the infant primary immunisation DTaP-containing vaccine doses is inadvertently or

deliberately given up to a week early (such as for travel) however, the impact on the final

response is minimal. If more than one dose in the three-dose schedule is given early, or one

of the doses is given at less than a three week interval, then that dose should be repeated at

least four weeks after the final dose. Where an infant dose of MenB is inadvertently given at

an interval of less than eight weeks, an additional dose should be administered four weeks

after the second dose to ensure adequate protection whilst still at a vulnerable age.

9

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

For other multiple dose schedules with inactivated vaccines e.g. hepatitis B, giving

subsequent doses at a slightly shorter than the recommended interval is unlikely to be

highly detrimental to the overall immune response. However, early vaccination should be

avoided unless necessary to ensure rapid protection or to improve compliance, and

additional doses may be recommended to ensure longer term protection.

Advice on intervals between different live vaccines is based on existing specific evidence of

interference between vaccines. The current advice is detailed in Table 11.3. Recommended

intervals between subsequent doses of the same live vaccine will depend upon the specific

incubation period of the vaccine virus, and other factors, such as decline in maternally

derived antibody. Please refer to the relevant chapters.

Table 11.3 Recommended time intervals when giving more than one live attenuated

vaccine

Vaccine combinations Recommendations

Yellow Fever and MMR A four week minimum interval period should be observed

between the administration of these two vaccines. Yellow Fever

and MMR should not be administered on the same day.

1

Varicella (and zoster) vaccine

and MMR

If these vaccines are not administered on the same day, then a

four week minimum interval should be observed between

vaccines.

2

Tuberculin skin testing

(Mantoux) and MMR

MMR vaccination and tuberculin skin testing can be performed

on the same day (Kroeger et al 2019). However, if a tuberculin

skin test has already been initiated, then MMR should be

delayed until the skin test has been read unless protection

against measles is required urgently. If a child has had a recent

MMR, and requires a tuberculin test, then a four week interval

should be observed.

3

All currently used live vaccines

(BCG, rotavirus, live attenuated

influenza vaccine (LAIV), oral

typhoid vaccine, yellow fever,

varicella, zoster and MMR).

Apart from those combinations listed above, these vaccines

can be administered at any time before or after each other.

This includes tuberculin (Mantoux) skin testing.

4

1 Co-administration of these two vaccines can lead to sub-optimal antibody responses to yellow fever,

mumps and rubella antigens (Nascimento et. al, 2011). Where protection is required rapidly then the

vaccines should be given at any interval; an additional dose of MMR should be considered.

2 A study in the US (Mullooley & Black, 2001) showed a significant increase in breakthrough infections when

varicella vaccine was administered within 30 days of MMR vaccine; suggesting that MMR vaccine caused

an attenuation of the response to varicella vaccine. When the vaccines are given on the same day, however

the responses have been shown to be adequate (Plotkin, 2018.) As the zoster (shingles) vaccine contains

the same virus as varicella (chicken pox) vaccine, this recommendation has been extrapolated to MMR and

zoster. Where protection from either vaccine is required rapidly then the vaccines can be given at any

interval and an additional dose of the vaccine given second should be considered.

3 Administering tuberculin (Mantoux) within 28 days of MMR vaccine may result in decreased reactivity of

the tuberculin and the false negative reporting of results. If tuberculin testing has already been initiated,

MMR should be delayed until the skin test has been read. If protection against measles is urgently

required, then the benefit of protection from the vaccine outweighs the potential interference with the

tuberculin test. In this circumstance, the individual interpreting the negative tuberculin test should be

aware of the recent MMR vaccination when considering how to manage that individual.

4 Whilst there is no evidence of decreased reactivity or interference from other live vaccines, those

interpreting the results of the tuberculin skin test should be aware of any recently administered live

injectable vaccines.

10

Chapter 11 -

The UK

immunisation

schedule

Chapter 11: The UK immunisation schedule 11 March 2022

References

Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance

of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/

general-recs/index.html. Accessed on January 10, 2019.

Mullooly, J and Black, S (2001). Simultaneous administration of varicella vaccine and other recommended

childhood vaccines – United States, 1995-1999. MMWR Weekly. Nov 30, 2001 / 50(47); 1058 -1061. http://

www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5047a4.htm

Nascimento Silva JR, Camacho LA, Freire Mde S et al (2011). Mutual interference on the immune response to

yellow fever vaccine and a combined vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella. Vaccine 29(37): 6327- 6334

Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA and Edwards KM, (eds) (2018) Vaccines, 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA:

Elsevier, [2018]