9

BILINGUAL EDUCATION

PROJECT

SPAIN

Evaluation Report

ALAN DOBSON

MARÍA DOLORES PÉREZ MURILLO

RICHARD JOHNSTONE

BILINGUAL EDUCATION PROJECT

SPAIN

Evaluation Report

Findings of the independent evaluation

of the Bilingual Education Project

Ministry of Education (Spain)

and British Council (Spain)

Alan Dobson

María Dolores Pérez Murillo

Richard Johnstone

Edited by Richard Johnstone

MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN

Instituto de Formación del Profesorado, Investigación e Innovación Educativa (IFIIE)

BRITISH COUNCIL, SPAIN

© 2010 Secretaría General Técnica.

Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones

Ministerio de Educación

© 2010 British Council, Spain

www.educacion.es

www.britishcouncil.es

Designed by: Charo Villa

NIPO: 820-10-477-2

ISBN: 978-84-369-4991-9

Depósito Legal: M.16.053-2011

Printer: Gráfi cas Muriel, S.A.

3

CONTENTS

Foreword Ministry of Education 5

Foreword British Council 7

Acknowledgements 9

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 11

Published outputs 11

The national BEP in Spain 11

The evaluation 16

CHAPTER 2: CLASSROOM PERFORMANCE & EFFECTIVE PRACTICE 23

Study 1: Primary 5&6 learners’ performance in class 24

Study 2: Primary School 5&6 good practice in class 32

Study 3: ESO1&2 learners’ performance in class 41

Study 4: ESO1&2 good practice in class 47

Study 5: Infants and early primary 55

CHAPTER 3: BEP STUDENTS’ ATTAINMENTS 63

Study 6: Primary 6 pupils’ oral interviews in English 63

Study 7: Primary 6 pupils’ writing in English 70

Study 8: Writing in Spanish: BEP and non-BEP compared 75

Study 9: Performance in an international examination 79

CHAPTER 4: PERCEPTIONS 85

Study 10: Students’ perceptions in Primary 6 and ESO1&2 85

Study 11: Parents’ perceptions of the BEP 98

Study 12: Primary School class teachers’ perceptions 104

Study 13: Secondary School class teachers’ perceptions 111

Study 14: Perceptions of Primary School head teachers 120

Study 15: Perceptions of Secondary School head teachers 128

Study 16: Management issues 136

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS

Challenges & outcomes 141

Attainments 142

Good practice 142

4

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Perceptions 142

Matters for reection and further development 143

Factors associated with successful outcomes 143

Further investigation 145

THE EVALUATION RESEARCH TEAM 147

5

FOREWORD

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION

In 1996 the Ministry of Education and Science and the British Council signed an

agreement to introduce an integrated curriculum in Spanish state schools. In this way

bilingual education was established in 43 state schools with 1200 pupils aged three and

four. Since 1996 bilingual education has slowly but surely been introduced at every level

of education from age three through to sixteen in the project schools.

In 2006 the results obtained and the interest this Bilingual Programme had aroused

both in Spain and abroad led the Ministry of Education and the British Council to ask

Emeritus Professor Richard Johnstone OBE (University of Stirling) to carry out an

independent external evaluation. The objective data obtained would be used to

fi ne tune the Programme. Professor Johnstone, together with Dr. Alan Dobson and

Dr Dolores Pérez Murillo, have devoted three years to a detailed analysis of every aspect

of the Bilingual Programme. The Ministry of Education would like to take this opportunity

to thank them for their work, especially where they have uncovered an area in need

of improvement.

These results, illustrated in this publication, allow the Ministry and the British Council

not only to develop the Programme further but also to put on record for the benefi t

of others in the fi eld of education the successful teaching practices revealed in the

evaluation.

We hope that the publication will be of interest and use both to language teaching

experts and to members of the general public interested in bilingual education.

Eduardo Coba Arango

Director of the Instituto de Formación del Profesorado, Investigación e Innovación Educativa (IFIIE)

Ministry of Education

Spain

7

FOREWORD

BRITISH COUNCIL

It gives me great pleasure to present to you this report on the fi ndings of an

independent three-year investigation into the Ministry of Education / British Council

Bilingual Schools project. Bilingual English/Spanish education is one of the most

exciting innovations in the current education scene, with over 200,000 young

students studying a bilingual curriculum from the age of 3, either in our project

schools or in regional government versions of the project based on this original

model.

The evaluation has been headed up by a leading world expert in bilingual education:

Professor Emeritus Richard Johnstone OBE of the University of Stirling, Scotland. He

worked with a close-knit team of two main researchers – Dr. María Dolores Pérez

Murillo from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and Dr Alan Dobson, formerly HM

Inspector at the Offi ce for Standards in Education (OFSTED) for England. I would like

to congratulate Professor Johnstone on this work and I am confi dent that with the

quality of this team we have in this publication a body of research that will become a

focal point of reference to everyone in Spain and indeed globally, who has an interest

in bilingual education.

Finally, I would like to express my sincere personal thanks to Pilar Medrano (Ministry

of Education) and Teresa Reilly (British Council) for their energy and commitment to

bilingual education, growing it from 43 schools in 1996 to the enormous network we

have today. It is with a high level of expectancy that I look forward to continue sharing

the vision with our partners in the Ministry of Education, a vision that is designed to

give young Spanish people the very best opportunity to equip them to be successful

in a modern, globalised, 21

st

century Spain.

Rod Pryde

Director British Council Spain

9

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My colleagues and I on the evaluation team consider it a great honour to have been

charged with the responsibility of conducting this important research study.

The fi ndings and conclusions of our study are entirely our own, and are fi rmly based on

the research evidence which we have collected. I should like to acknowledge the full

acceptance of this independence by the Ministry of Education and the British Council,

and at the same time my colleagues and I wish to record our grateful thanks to them

for always being helpful and considerate.

Our task was to gather high-quality evidence on this one project, in order to learn

whether or not it was achieving its aims. Our task was not to compare it with other bilingual

education projects in Spain or elsewhere. Spain has made an impressive commitment to

early bilingual education in several different ways, through a variety of different projects

and involving a number of languages. We wish all of them well, but we seek to make no

comparisons and our report limits itself to the one project which we were charged to

evaluate.

My colleagues and I are indebted to a large number of people across several

different groups, such as school managers, class teachers, pupils & students, parents,

regional authorities, staff involved in research and teacher education, and one

prestigious external examination board (University of Cambridge International

Examinations). Conducting an evaluation in schools inevitably causes some degree

of inconvenience, and so we would like to thank all of those with whom we have been

in contact for the welcome they have afforded us and the interest in our research

which they have shown.

My fi nal word of thanks must go to my two research colleagues in the evaluation team,

Dr Alan Dobson and Dr María Dolores Pérez Murillo, for the excellent work they have

done in collecting and analysing data, preparing draft reports and contributing to our

study in many different ways; and I should also like to express my grateful thanks to

Margaret Locke for her skill, tact and patience in facilitating many of our arrangements

with schools.

10

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

It is our sincere hope that our evaluation report will be of interest and use not only

to those directly involved in the project which we have been evaluating but also to

anyone who has an interest in children’s education through language at school.

Professor Emeritus Richard Johnstone

Director, Independent Evaluation of

National Bilingual Education Project (Spain)

11

This introductory chapter has three sections:

•

A brief note on the published outputs of the evaluation study

•

A description of the national Bilingual Education Project (henceforth, BEP) which is

the object of the evaluation study

•

Key features of the evaluation study.

PUBLISHED OUTPUT OF THE PRESENT EVALUATION STUDY

The main published output of the BEP evaluation will consist of the following texts:

•

The present Evaluation Report which sets out the background to the study and

the key ndings. This is the text which is intended for a wide-ranging readership. It

is published both as a printed book, made available in a limited number of copies,

and is also available on-line

1

.

Given the importance of presenting the Evaluation Report in both Spanish and English

within the one printed publication, there is a limit on the number of pages available for

either of these two languages, and as a consequence the Evaluation Report cannot

contain certain aspects in which some potential readers might be interested.

Accordingly, by May 2011 it is intended to make available:

•

An online Supplement which will contain an article setting the BEP against the

background of international research on bilingual education, which will offer

some additional thoughts on good practice and which will provide further detail

on the research approach that was adopted, e.g. the different instruments and

procedures that were used for data-collection and analysis, and presenting

some additional statistics and ndings.

THE NATIONAL BEP IN SPAIN

The national BEP in Spain began in 1996, following an agreement between the Ministry

and the British Council. It derived its inspiration from the British Council School in

1. The two published outputs mentioned above will be available on the websites of both the Ministry of Education (Spain)

and the British Council (Spain).

chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

12

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Madrid but soon assumed its own distinctive identity as a programme explicitly

intended for pupils in the Spanish state school system.

According to senior gures within the BEP, one of the reasons for initiating an

early bilingual education programme was an increasingly widespread feeling of

dissatisfaction among teachers and parents in Spain with the outcomes of what might be

termed the mainstream model of teaching a Modern (foreign) Language at Primary School

(MLPS), based on relatively small amounts of time per week being made available. This

perception of the limitations of the MLPS model is given authority by a review of research

on this topic across the European Union, sponsored by the European Commission, in

which the authors (Blondin et al, 1999)

2

found that, although pupils’ attitudes to MLPS

were generally positive, there was only limited evidence of pupils having developed

a uent, exible and accurate command of their foreign language by the end of their

primary school education.

By contrast, an early bilingual education approach offers in principle three potentially

key factors which differentiate it considerably from MLPS. These are:

•

an early start (in some cases beginning at the age of three)

•

a signicant increase in ‘time’ for the learning and use of the additional language,

and

•

an increase in ‘intensity of challenge’, in that pupils are challenged not only to

learn the additional language but also to learn other important primary school

subject-matter and to develop new skills through the medium of that language.

Aims of the national BEP in Spain

The published aims of the national BEP in Spain as set out in the ofcial Guidelines for

the Integrated Curriculum Primary (p. 87) as approved by the Ministry of Education in

Spain are:

•

To promote the acquisition and learning of both languages through an integrated

content-based curriculum.

•

To encourage awareness of the diversity of both cultures.

•

To facilitate the exchange of teachers and children.

•

To encourage the use of modern technologies in learning other languages.

•

Where appropriate, to promote the certication of studies under both educational

systems.

Key characteristics

The BEP possesses the following key characteristics:

•

It operates in state schools and not in schools that are private or fee-paying.

2. Blondin, C., M. Candelier, P. Edelenbos, R. Johnstone, A. Kubanek-German and T. Taeschner (1999). Foreign languages in

primary and pre-school education. A review of recent research within the European Union. London: CILT.

13

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

•

It begins at an early age, normally when pupils are three or four years old.

•

It is based on a whole-school

3

approach, in order to ensure that all children at

the school have the same opportunity, regardless of socio-economic or other

circumstances.

•

It is supported by a set of Guidelines

4

which were shaped not only by staff of the

Ministry and British Council but also by participating teachers.

•

Before a school joined the BEP, there was a visit by staff from the British Council

and/or Ministry, in order to discuss with staff and parents what the programme

meant and to check that they were in favour of the school’s participation.

•

A signicant amount of curricular time is allocated to the additional language (in

this case, English), roughly equivalent to 40% of each week at school, allowing

pupils to learn a number of challenging subjects through English such as science,

history and geography.

•

The skills of reading and writing in English are introduced from an early point, in

order to complement the skills of listening and speaking and to promote an

underlying general competence in language.

•

From the beginning there was agreement with the associated secondary schools

that when the BEP pupils entered secondary school, they would continue to

receive a bilingual education.

•

The schools are situated in ten of the seventeen autonomous regions of Spain, plus

Ceuta and Melilla, covering a range of socio-economic, ethnic, linguistic and other

contexts; they were not selected on the basis of social or other privilege.

•

Supernumerary teachers were made available to each participating school in

order to support the everyday classroom teachers in implementing the EBE

programme.

•

Further support at national level was made available through the appointment

of a key person in each of the Ministry and the British Council who jointly oversee

the project, visiting schools, arranging for initial training and for Continuing

Professional Development (CPD) and also through the appointment of staff in the

British Council whose tasks include liaison with schools, development of a BEP

website, and production of a magazine (entitled Hand in Hand).

Schools and teachers

Initially, forty-four primary schools were involved in the BEP. Of these, only one has

dropped out. It was agreed at an early stage that the number of schools would not be

3. This means that when a primary school embarks on the BEP, all classes in the rst year receive the same early bilingual

education (EBE), thereby avoiding a two-track approach (in which one track has EBE and the other a mainly monolingual

education in the national language). When classes in the rst year move up to the second year, their EBE continues, so that

when the rst cohort have reached the nal year of primary school education, the whole school is being educated bilingually.

4. These Guidelines were subsequently endorsed by the Spanish Ministry as reecting a curriculum which was considered to

be appropriate for EBE and also was acceptable as a valid curriculum for children at school in Spain.

14

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

increased until the rst cohort of pupils had completed their bilingual education at primary

school and had continued this for at least three years at secondary school. In the school

year 2008-2009 there were 74 primary schools and 40 secondary schools involved in

the BEP, distributed as follows:

Aragón (21 primary /4 secondary); Asturias (2/2); Baleares (2/2); Cantabria (1/1);

Castilla-La Mancha (7/7); Castilla y León (19/10); Extremadura (2/0); Madrid (10/10);

Murcia (2/1); Navarra (6/1); Ceuta (1/1); Melilla (1/1).

There were signs in 2009, however, of a possible decrease in the numbers of

secondary schools participating in the national BEP. This should not be taken as a

sign of disaffection with Bilingual Education, however, since in certain areas a regional

BEP has been developed with the secondary schools in the national BEP engaging

with their regional scheme in some cases.

Teacher appointments in state schools in Spain

In state schools in Spain, most of the teaching is done by funcionarios (teachers with

civil service status and conditions) who are appointed following a series of competitive

examinations (oposiciones). Some teaching is done by teachers on temporary appointment

waiting to present themselves for these examinations (interinos). Funcionarios may hold a

plaza ja (a permanent appointment to a specic school). Those who do not have a plaza

ja may be transferred to another school at the end of the school year.

Contracted teachers delivering BEP

When the BEP was set up in 1996, it was recognized that, although there were some

funcionarios with good English, stafng resources needed to be supplemented by native

(or near-native) speakers of English, and appointments of asesores linguísticos (AL)

5

were made. The number of AL varies at present from three to ve across the schools

according to their size. In the year 2008-2009, there were 231 contracted teachers of

this sort working in primary schools.

In 2004, when the rst cohort of pupils moved on to secondary education, individual

regional authorities (comunidades autónomas CCAA

6

) decided whether to appoint

contracted teachers to teach in secondary schools (ESO) or whether to use subject

teachers from their own workforce deemed to have adequate language skills. In 2008-

2009, there were fourteen ALs appointed in secondary schools in six of the regional

authorities, to teach science (ciencias naturales – CN) or social science (ciencias sociales – CS).

(CS includes geography and history).

5. This is the term most frequently used for contracted teachers on the BEP but the actual term used may vary from one

region to another.

6. In October 1999, the responsibility for education in Spain was given to the CCAA and they are now responsible

for the contractual conditions of teachers employed on the BEP. However, the overall role of the Ministry of Education and

the British Council in the project is to offer advice, support and expertise in areas such as recruitment and teacher

development.

15

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

The contracted teachers were distributed as follows:

Per CCAA (primary / secondary: CN & CS): Aragón (53 / 0); Asturias (8 / 4: 2 & 2);

Baleares (6 / 2: 1 & 1); Cantabria (2 / 2: 1 & 1); Castilla-La Mancha (25 / 0); Castilla y

León (59 / 0); Extremadura (7 ); Madrid (42 / 0); Murcia (6 / 2: 1H & 1S); Navarra (13 /

0); Ceuta (5 / 2: 1 & 1); Melilla (5 / 2: 1 & 1)

Some of the regional authorities chose to use foreign language assistants (FLA)

(auxiliares de conversación) as well as or instead of AL in order to support teachers in

secondary schools. The number of FLA varies between one and four across the schools,

but there are no overall gures available for the number and distribution of these

appointments in the BEP schools across the regional authorities.

Recruitment of supernumerary teachers

For recruitment to primary schools involved in the BEP, applicants are expected to have

a native or near-native command of both spoken and written English, have recognized

European QTS (Qualied Teacher Status) in infant/primary teaching (exceptionally

teachers with secondary PGCE (Postgraduate Certicate of Education) or TEFL

(Teaching of English as a Foreign Language) qualications may be appointed) and

have had classroom experience with children between three and eleven years of age.

For teaching their classes in BEP secondary schools teachers are expected to have a

native or near-native command of both spoken and written English, hold a recognized

degree in a relevant subject and recognized European QTS in secondary teaching, and

have had classroom experience with children between 12 and 16.

Working arrangements

The ALs

7

are additional members of staff and are not in charge of any one class, i.e.

they are not class teachers. Timetables vary and teachers are expected to be exible.

Teachers on the BEP can expect to be employed in infants (3-6 years) or primary

(6-12 years) but in some schools teachers teach within both areas.

The AL, particularly at the infant stage, works alongside the class teacher or takes

the whole class for games, stories, reading and writing and other curriculum input.

However, in primary the AL is often, though not always, left in sole charge of the group.

Spanish teachers of English have been gradually brought on board to help deliver a

curriculum which includes subject areas from both the Spanish and the English national

curriculum.

In the ten comunidades (plus Ceuta and Mellila), every school has a maximum of four

ALs. One or two still have ve but once the fth has left, she/he is not replaced. A consi-

derable sum is invested in training Spanish teachers of English, and after two years there

should be less dependence on the ALs as the ‘only’ deliverers of the English component.

In secondary schools, there is a specic need for co-operation and coordination

between departments. The CN and CS teachers are expected to work closely with the

7. Although commonly referred to as ‘British’ in the schools, some of the AL may be from the Commonwealth, the USA or the

Republic of Ireland; some are Spanish teachers with a near-native command of English.

16

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

English teachers, often planning together how the English department can support

the CN and CS teachers through, for example, the teaching of specic language skills,

areas of vocabulary, developing reading and writing skills and non-ction texts which

might focus on teaching and developing the specic language of instruction, prediction,

report writing etc.

The contracted teachers are on renewable annual contracts and do not have the same

conditions as funcionarios; for example they do not receive trienio, i.e. an entitlement

after three years of service.

INSET and Staff Development

Each year in early September the Ministry and the British Council organise a short

induction course for newly appointed contracted teachers.

A programme of staff development for teachers on the BEP is jointly run by the Ministry

and the British Council.

THE EVALUATION

The evaluation was funded jointly by the Ministry of Education (Spain) and the British

Council as an independent evaluation of the national BEP in Spain. After initial

discussions involving the Director of the evaluation and ofcials of the Ministry and

British Council in 2005, the evaluation began in 2006. At a much earlier stage in the life

of the BEP there had been an initial smaller-scale evaluation, designed to provide

feedback on how the BEP was faring in its initial development, and this study among

other things strongly supported a ‘whole-school’ approach.

Aims of the evaluation

The evaluation had three agreed aims:

Aim 1:

•

To provide research-based evidence on pupils’ English language prociency as

developed and demonstrated through the study of subject matter in a bilingual

context; and on their achievements in Spanish.

Aim 2:

•

To identify and disseminate good practice as occurring in the project schools.

Aim 3:

•

To provide research-based evidence on awareness, attitudes and motivation.

8

8. In fact, in the agreement between the funding bodies and the Director of the evaluation, Aim 1 and Aim 3 were conated as

one Aim, but in order to avoid possible confusion they are treated separately throughout the present report as two separate

Aims (Aim 1 and Aim 3).

17

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Research questions

After discussion with the two funding bodies, four main research questions or themes

were agreed which would reect the above three general aims. These are stated here in

research question (RQ) form:

RQ1

•

How may the performance and attainments of BEP students be described?

RQ2

•

What evidence is there of ‘good practice’ and how may this be dened and

exemplied?

RQ3

•

How is the BEP perceived by key groups which have a stake in it?

RQ4

•

Is the BEP achieving the aims which it has set out for itself?

Roles of research staff

The research staff consisted of two Research Consultants, one Research Administrator

and one Research Director.

It was mainly the role of the research consultants to assist in developing the research

instruments, to visit schools, to collect and analyse data and to draft reports. As a matter

of principle, one of the two research consultants was from the UK, with English as rst

language but with high prociency in Spanish, and the other was Spanish, with Spanish

as rst language but with high prociency in English. All members of the evaluation

team were employed on a part-time basis and two of them were based outside Spain,

so it was important to design an evaluation study which would be conducted efciently

within the resources available. The Director took responsibility for the overall evaluation

strategy, for networking with the two research consultants, for liaison with the two

funding bodies, and for undertaking certain Studies in collaboration with colleagues.

Given the stafng of the evaluation team, inevitably much of their communication with

each other took place individually at a distance, by email, text-messages or phone. Each

year, however, there were minimally two or more formal meetings of the full team in order

to discuss plans and to report on progress. The meetings took place in private at the

ofces of the British Council in Madrid or London, and towards the end of most meetings

the two key contact persons representing the funding bodies were invited to join the

meeting. This enabled information on progress to be presented and also a constructive

informal discussion to take place of any issues which seemed to be arising. In addition,

a more formal interim report on progress was presented at the Ministry of Education to

a group representative of the Ministry and the British Council in 2007.

18

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Increasing scope of the evaluation

Initially, main focus on primary schools

The initial understanding agreed by the funding bodies and the evaluation team was

that, given the resources available for the evaluation, it would be important to focus

on key points rather than attempt to cover every conceivable point of interest.

Accordingly, it was agreed that the main focus of the evaluation team’s efforts should

be on the BEP at primary school. There was good reason for this, in that the BEP

was well-established in primary schools but had moved into the associated secondary

schools only in recent years, and it seemed reasonable to surmise that perhaps

the secondary schools in some cases were still ‘coming to terms’ with the BEP. Although

classes in all years of primary school education, and also in infants’ classes, were

observed, it was agreed that the main focus in primary schools should be on the third

cycle of primary education, i.e. the nal two years which we shall term Primary 5 and

Primary 6. The reason for this preference was that it would enable a picture to be built up

of what the outcomes of the BEP were by the end of pupils’ primary school education.

Extending the scope in the light of emerging issues and needs

As the work of the evaluation team got underway, a case began to emerge for making

some modication to the scope of the evaluation as set out above. Four issues in

particular were becoming salient:

1. With regard to RQ3, the main groups intended for consultation had been students,

class teachers and Head Teachers, but interest grew in incorporating a parents’

perspective also, so this was agreed.

2. The rst cohort of BEP students to reach ESO4 (fourth year of secondary

education) did so in Autumn 2007 and became available for taking the Cambridge

IGCSE

9

examination towards the end of ESO4 in 2008. Interest arose therefore in

tracking students’ attainments at that level. It was considered essential to situate

these attainments in context, and so it was agreed with the funding bodies that

there should be additional data-collection from secondary schools beyond the

data-collection on primary-secondary transition that had originally been

envisaged. As a consequence, data-collection took place by means of classroom

observation of lessons in ESO1&2 (Secondary 1 & 2), the collection of ESO2

students’ perceptions, and questionnaire surveys of ESO2 students, secondary

school class teachers and Head Teachers, in addition to taking note of ESO4

students’ attainments in the IGCSE.

3. The evaluation team was becoming aware of some concerns that maybe BEP

students’ command of Spanish was being compromised as a result of having

some 40% of their education in another language. It was agreed therefore that a

9. IGCSE stands for International General Certicate of Secondary Education.

19

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

comparison study should be undertaken in which BEP and non-BEP students would

be compared in respect of their written Spanish. However, this could not take place

in BEP primary schools because all classes were taking the BEP, so it had to take

place in the associated secondary schools which from rst year of secondary

education onwards had two sorts of intake: BEP and non-BEP. Accordingly, a

comparative study of BEP versus non-BEP in respect of writing in Spanish was

agreed for ESO2 (second year of secondary education).

4. In order to address RQ1 as fully as possible, it was agreed that account should

be taken of the performance of BEP students towards the end of ESO4 (fourth

year of secondary education) in the international IGCSE examinations. The rst

cohort of BEP students to reach ESO4 did so in school session 2007/8, and a

number of schools presented candidates for the IGCSE in summer 2008; to

be followed by a larger number of schools and candidates in summer 2009.

Accordingly, it was agreed that evidence should be collected on the IGCSE

performance of BEP students, particularly in 2009.

There was no request from the funding bodies for a comparative study of the

‘experimental versus comparison’ sort. In other words, the evaluation team was not

asked to compare the attainments of BEP pupils with non-BEP pupils of the same age.

It is quite common for evaluation studies to make this sort of comparison; however in

the present case it was not requested. Therefore, the focus was on the BEP itself as

a distinctive entity with its own aims, processes and values, and not on the BEP

as being better or worse than the existing mainstream curriculum in Spain (nor indeed

as being better or worse than any other bilingual education initiatives in Spain or else

where). By its very nature, the BEP offers a radically different education from the

mainstream system and it was therefore important to learn whether it was achieving its

own different ends. The one exception to this principle was the ‘comparison study’ of

BEP versus non-BEP students’ Spanish writing which has already been mentioned.

Selection of schools

In consultation with the two funding bodies, and taking account of the stafng resources

available to the evaluation team, the following selection of schools was agreed:

Sample A: Schools which would be visited and surveyed

Eight primary schools were identied for purposes of periodic visiting, taking into

account geographical distribution, social spread and school size, as well as a likelihood

of nding some instances of good practice. Careful attention was paid to the known

socio-economic and other background of these schools, in order to ensure that this

sample as far as possible reected normal state schools in Spain and did not constitute a

privileged élite.

In addition, there were three primary schools which contained special features of interest,

e.g. their socio-economic (under-privileged) background or linguistic prole (high

incidence of rst language other than Spanish). These three schools would receive one

visit each. Also to be visited would be the ten secondary schools associated with these

20

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

primary schools (one BEP primary school did not have an associated secondary school),

making a total of 21 schools, sixteen of which would receive periodic visits and ve of

which would receive single visits.

Sample B: Schools which would be surveyed but not visited

An additional broader sample of 26 schools (thirteen primary schools and thirteen

associated secondary schools) was also selected for purposes of collecting more

representative data. While one particular school was chosen to represent one particular

comunidad where it was the only project school, the remaining schools were selected

randomly, conditional on representing a wide geographical spread. These schools

would not be visited but would be consulted by means of a periodic survey on specic

issues which would be the same surveys as for schools in Sample A above.

The 16 studies undertaken by the evaluation team

At an early point in their deliberations the evaluation team rejected the notion of one

large-scale intervention designed to catch everything. This might have been economical

on ‘time’ and on ‘visits to schools’, but it would be highly unlikely to capture any clear

or convincing picture of ‘good practice’. In order to understand what might constitute

‘good practice’ in the BEP, the evaluation team attached high importance to making

several visits to a limited number of schools rather than one visit to each school in

the programme overall. The several visits would avoid any problems arising from

unrepresentative, specially prepared, ‘one-off’ demonstration lessons and would enable

initial ideas on ‘good practice’ to emerge and then to be conrmed, disconrmed or

rened. That is why the sampling procedure as already described was adopted: visits

to the inner sample primary schools (backed up in due course by visits to their associated

secondary schools) would yield rich information on ‘good practice’, while more

contextual information on perceptions and attainments would be collected from the

primary schools in the wider sample further supplemented by their associated secondary

schools.

In order to address the two stated aims of the evaluation, it was decided to implement

sixteen different data-collection studies, each with a different focus and with differing

numbers of schools involved, depending on what was feasible for the evaluation group.

These sixteen studies generate the main data on which the present report is based.

It is important to state, however, that before any of these sixteen studies took place,

the members of the evaluation team made visits to several of the Sample A schools in

order to establish initial contacts, make themselves known to the staff, talk about what

the evaluation was likely to involve, and to collect such materials and documentation

as the schools wished to make available regarding the school in general or the BEP in

particular within the school. Where possible, the two research consultants made joint

visits to these schools, in order to develop shared understandings and to exchange ideas.

In addition, members of the evaluation team familiarised themselves with the BEP in

other, less direct ways, e.g. by attending, and in some cases participating in, courses or

conferences which involved BEP and possibly other teachers. This proved a highly useful

21

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

procedure, since it enabled the evaluation team to learn about the BEP from practitioners

talking about particular aspects of the BEP as implemented in their particular schools.

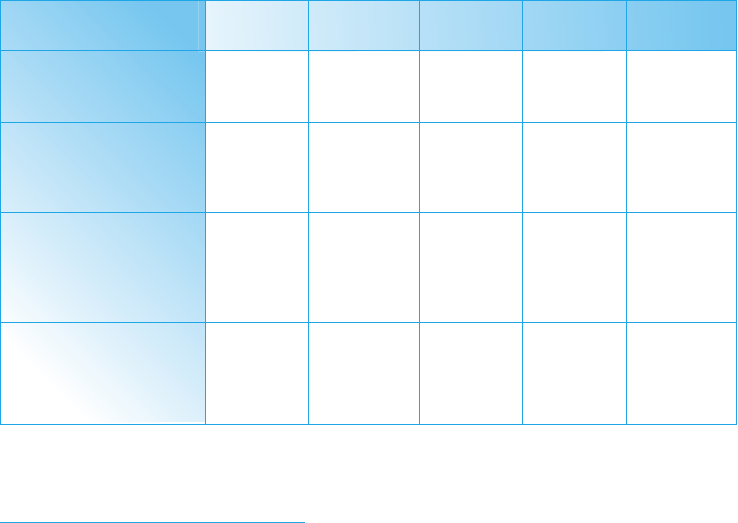

The sixteen key studies which the evaluation team undertook are set out below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Primary 5&6 learners’

performance in class

Good practice associated with

P5&6 classrooms

Secondary 1&2 learners’

performance in class

Good practice associated with

S1&2 classrooms

Infants and early primary

P6 pupils’ oral assessments in

English

P6 pupils’ writing in English

Secondary 2 students’ writing

in Spanish: BEP compared with

non-BEP

Secondary 4 students’

attainments in an international

external examination

Primary 6 and Secondary 2

students’ perceptions

Primary 6 and Secondary 2

parents’ perceptions

Primary school classeachers’

perceptions

Secondary school class

teachers’ perceptions

Primary school Head Teachers’

perceptions

Secondary school Head

Teachers’ perceptions

BEP management issues

Performance

Attainments

Good Practice

Performance

Attainments

Good Practice

Peformance

Attainments

Good

Practice

Performance

Attainments

Performance

Attainments

Performance

Attainments

Attainments

Perceptions

Perceptions

Perceptions

Perceptions

Perceptions

Perceptions

Perceptions

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

All

presenting

schools

A+B

A+B

A+B

A+B

A+B

A+B

A+B

Systematic observation

Systematic observation

Systematic observation

Systematic observation

Systematic observation

Assessment interviews

Scrutiny of students’

written texts under

controlled conditions

Students’ written

composition

Scrutiny of published

results plus notes on

performance of BEP

candidates authorised by

IGCSE Board

Questionnaire survey

Questionnaire survey

Questionnaire survey

Questionnaire survey

Questionnaire survey

Questionnaire survey

Questionnaire survey

Study Títle

Main

themes

Sample

Methodology

key words

22

PEB. EVALUATION REPORT

In the opinion of the evaluation team, these sixteen studies present a substantial set

of diverse data, considerably wider in range than what many evaluation studies have

attempted, but all of it relevant to the agreed aims and RQs of the evaluation study. A price

to pay has been the fairly small number of schools involved in some of the studies, but

the evaluation team believes that the large number of studies, each of which has probed a

different aspect of the national BEP in Spain, has generated interesting insights into what

was actually happening and into what key stakeholders actually thought. Many of these

insights would not have been possible if there had been a smaller number of studies but

with a larger number of schools.

Code of practice

The evaluation team welcomed the fact that the two funding bodies attached high

importance to the independence, objectivity and integrity of the evaluation. In order to

realise these principles, the evaluation team committed itself to a Code of Practice. This

is too detailed to be included in full in the present report, but some of its main features

are set out below.

Examples from evaluation team code of practice

•

Behaving fairly, transparently and independently, and in a consultative manner

•

Minimising inconvenience when visiting schools or collecting data

•

Contacting schools through an agreed procedure, in order to seek their agreement for

visits or other means of data-collection

•

Providing advance information in respect of visits

•

Securing the prior agreement of schools for all modes of data-collection

•

Maintaining anonymity, i.e. not relating any ndings, or interview data or observation data,

or other information to any named individual or school

•

Maintaining condentiality, i.e. not allowing unauthorised information or ndings to ‘leak

out’ into the system prior to proper publication of the report

•

Ensuring the security of data, so that it does not pass into unauthorised hands

•

Focussing exclusively on the aims of the evaluation

•

Not promoting the cause of early bilingual education, nor seeking to represent either

funding body, nor troubleshooting if problems in schools are observed.

23

Studies 1-5 are all based on detailed classroom observation.

Studies 1 & 3 identify aspects of pupils’ learning as exhibited in everyday classroom

activity, in the one case mainly with Primary School Year 5 and 6 classes and in the other

mainly with classes in Secondary 1 and 2 (ESO1&2). The illustrations offered are typical of

what an evaluator heard and saw during the observation of lessons. As in most classroom

situations elsewhere, some students in the lessons observed contributed more actively

(or audibly) than others who were equally able but more reticent or than some who were

less able. It is not assumed that the performances were ‘typical’ of every pupil in the

lessons observed, but the illustrations are representative of the performance of pupils

witnessed in interaction with their teacher and each other across the sample of schools.

Studies 2 & 4 provide evidence on the classroom practices which were associated

with the types of learning performance identi ed in Studies 1 and 3. We use the term

‘associated’ advisedly; we are not in a position to claim that the classroom practices of

Studies 2&4 ‘caused’ the positive classroom performance of Studies 1&3, but they were

certainly associated with them.

As has already been stated, the main focus of the evaluation at primary school level was

on Years 5&6, but the opportunity was taken also to observe teaching and learning with

younger age-groups, and this is reported in Study 5.

A note on the methodology of Studies 1-5

In all ve studies, the data-collection was based on a form of participant observation that

was devised so as to be appropriate for the evaluation, with the researcher participating

in an observer role. The term ‘evaluation’, especially when applied to a prestigious

national programme, can carry a heavy meaning. It was therefore considered essential to

collect data in a way that was as user-friendly as possible and in keeping with the code of

practice as set out in Chapter 1. It was decided therefore not to audio-record the lessons

because this would have been intrusive and might have disturbed the naturalness of

the setting. It was decided also not to develop a highly detailed observation schedule,

on the grounds that these bilingual classrooms in Spain were for the researchers

a relatively new phenomenon and it would not be appropriate to impose a detailed a

priori system. Instead, it was considered essential for the evaluator to be ‘open’ to any

incidents or interactions which occurred in order to gain an overall feel for the situation

and then to work towards a sense of what seemed salient to the notions of learner

performance and good practice.

chapter 2

CLASSROOM PERFORMANCE &

EFFECTIVE PRACTICE

24

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

As each lesson proceeded, the evaluator took detailed notes, including precise notes of

exactly what was said by teacher or student in episodes which seemed salient.

The quotations are an exact representation of the words uttered, but use is not made of

a phonetic or other form of academic research-based script. The quotes are reproduced

in standard written English script. This poses limitations, in that spoken language and

written language operate according to different systems, but has the advantage of being

accessible to a wide readership. Soon after each lesson the evaluator converted these

notes into a more coherent text and added any personal reections which seemed

appropriate, making sure that eventual readers would be entirely clear as to what was

factual report and what was reection.

These more coherent notes form the basis of the texts of Studies 1-5. Analysis of these

texts plus further more summative reections are set out in the Key Points sections

which conclude each study.

In the ve Studies which follow:

•

the factual report is in black

•

what was said by pupils and teachers is in blue and is placed between single quotes

•

extracts from the researcher’s observation notes are placed between double quotes

•

personal reections or further recollections which the researcher introduced

subsequently are integrated with the text in separate paragraphs beginning with

the indication Notes.

STUDY 1:

PRIMARY 5&6 LEARNERS’ PERFORMANCE IN CLASS

This study focuses on the performance that pupils typically demonstrated in science and

in language & literacy lessons by the end of the third cycle of primary education.

Introduction

The analysis is based mainly on an analysis of lessons from ten of the Sample A schools

and partly on group interviews in six of the Sample A schools. During the lessons, notes

were taken on an observation sheet. As soon as possible after a lesson the notes were

written up in more complete form and key points were extracted which were judged

to provide evidence of some aspect or other of what pupils could do in their everyday

classroom interactions.

The observations of Year 5 lessons are included in the analysis and illustrations below

since they provide further evidence of what pupils can achieve during the third cycle

of primary education. Where the examples are from Year 5, this is clearly stated. The

availability of evidence was partly determined by the timing of the visits which had to take

other constraints into account.

25

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Opportunities for listening and speaking

Most pupils were motivated and participated in some way in almost all the lessons seen.

There were various examples of pupils being effectively engaged through question and

answer activities in whole-class situations. However, pupils were much more likely to

have opportunities in lessons to respond to, rather than give, instructions and to answer,

rather than ask, questions. Although there were opportunities for pupils to interact

with their teacher in almost all classes, opportunities for them to interact with each other

were limited in about half the lessons seen.

In science lessons, pupils in Year 6 covered a range of topics, for example the respiratory

system; ecosystems; and climate zones. Consequently, in lessons they were exposed

to, and expected to cope with, a range of specialist terms including: ‘pharynx, larynx,

trachea; echinoderms, arachnids, crustaceans; desert, rain forest, savannah’.

In language & literacy lessons, pupils in Year 6 covered a range of topics, including

Halloween, a history of chocolate, the Tsunami of 2004 and various stories such as

those of Roald Dahl. The texts they encountered covered a wide and often demanding

range of vocabulary, for example: ‘ghost, phantom, spectre, apparition; ladybird,

grasshopper, seagull, centipede; cacao’.

Using listening and speaking skills

Following up lessons and responding to teachers’ questions

In interaction with the teacher, the great majority of pupils were apparently able to follow

a lesson incorporating specialised vocabulary. They were able to cope with the teacher’s

questions and show understanding of concepts, for example when recapping:

(Circulatory system)

Q: ‘What is the difference between the red and the blue lines (on the poster)?’

A: ‘Arteries (red) carry oxygen and veins (blue) carry away harmful substances.’

(Climate zones)

Q: ‘Where are the temperate zones?’

A: ‘They go from the tropics to the polar circles.’

On a range of topics the pupils were able to develop and consolidate their knowledge and

understanding through dialogue with the teacher.

The sense of sight

During a recap of work on the sense of sight, pupils had to explain each component part

(retina, cornea, etc on a plastic model), for example:

T: ‘What is this part called?’

P: ‘The retina.’

T: ‘How does it function?’

P: ‘First the light enters through the pupil and reaches the retina…’

26

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

The nervous system

Similarly, pupils were expected to explain aspects of the functioning of the nervous

system:

T: ‘What is the function of the nervous system?’

P: ‘It controls everything.’

T: ‘How many the cells are there in the brain?’

P: ‘Millions?’

P: ‘Billions?’

T: ‘Hundreds of billions.’

T: ‘What are nerve cells called?’

P: ‘Neurons.’

T: ‘What does the cerebellum do?’

P: ‘It controls coordination and balance.’

T: ‘What does the brain stem do?’

P: ‘It coordinates with rest of the body, it controls all the systems…’

Materials

Pupils identied cotton as a natural material. The teacher asked: ‘Why is it natural?’

One pupil replied ‘because it comes from a plant’; another that ‘it comes from

cotton owers’. The pupils are willing to have a go, particularly boys. For example, one

improvised to explain ‘dry grass’ (straw) was used in making bricks out of clay in former

times. Another in reply to the teacher asking about a rubber band ‘Where is it from?’

stated ‘part of a tree’ (Y5).

The Stone Age

Pupils beneted from whole-class question and answer mode: this motivated pupils and

drew out suitable contributions as in a Year 5 lesson about life in palaeolithic times:

Q: ‘What is pre-history?’

A: ‘It’s a long period of time before documents existed.’

Q: ‘Why is the Stone Age so called?’

A: ‘Because everything that survives from (human activity) then is made of stone.’

Q: ‘What is the stone called that is very important for pre-history?’

A: ‘Flintstone.’

Q: ‘Where did Stone Age people live?’

A: ‘In caves.’

Q:’ Did they have permanent addresses?’

A: ‘No.’

Q: ‘Why?’

A: ‘Because they were nomads.’

Q: ‘How many jobs were there in the Stone Age?’

27

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

A: ‘Two - gatherers and hunters.’

Q: ‘Who was in charge of hunting?’

A: ‘The men.’

Q: ‘What did the women gather?’

A: ‘Fruit, vegetables.’

Q: ‘What do we mean when we say animals are extinct?’

A: ‘They don’t live any more.’

Offering explanations

The rain cycle

In a discussion about the rain cycle, pupils offered various explanations in their own words

‘the water escapes from the sea into clouds. The clouds go up the mountains… (girl);

the sun makes the water hot and it goes up in clouds.’ (boy). When pupils did not recall

the precise words to explain, they were sometimes able to improvise, for example:

T: ‘What is the problem (about shortage) if there is lots of water (on the world’s

surface)?’

P: ‘It’s with salt.’

The sense of hearing

From a discussion concerning the ear:

T: ‘What happens when you have a cold?’

P: ‘Mucus goes through the Eustachian tube into the middle ear.’

T: ‘How does the doctor know this if he cannot see into the middle ear?’

P: ‘He sees a change in the position of the eardrum.’

States and properties of materials

The teacher expects the pupils to give examples of liquids, solids, gases etc; they

offer: ‘oxygen, nitrogen, helium, carbon dioxide’ etc. as examples of gases.

There are plenty of volunteers to provide explanations, for example about liquids:

‘If a liquid is not in a container, it will spill (spread) out.’ (boy)

‘If we pour a liquid from one container to another, it changes shape.’ (boy)

‘If you put the water from the jar into the beaker, it will take the shape of the new

container. The shape of the water change’ (sic) (girl).

‘We can see that solids can be different. They have different volume and matter.’

(girl)

Types of energy

From a discussion concerning electrical and chemical energy:

T: ‘What happens in a fan?’

28

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

P: ‘Electrical energy is converted into mechanical energy.’

T: ‘What happens in a car?’

P: ‘Chemical energy is converted into mechanical energy.’

Physical and chemical changes:

In another class, examples of chemical changes were identied such as ‘cooking,

burning, fermenting’. The class were invited to say which substances ferment.

Examples given by pupils included ‘milk changing into yoghourt, apples into cider’.

An experiment followed with teacher commentary supported by cuecards:

‘This is a powder called bicarbonate. We’re going to pour some bicarbonate into

the balloon. Then we pull the mouth of the balloon over the mouth of the bottle

and mix the bicarbonate and the vinegar...’ (The mixture produces bubbles and gas

rises inating the balloon.)

Pupils summarized what they had seen, for example:

P: ‘We poured the liquid (vinegar) into the glass bottle.’ (girl)

P: ‘We put the bicarbonate into the balloon.’ (boy).

T: ’ What did we do next?’

P: ‘We pulled the mouth of the balloon on to the mouth of the bottle.’ (boy).

P: ‘We mixed the bicarbonate with the vinegar.’ (boy)

Offering statements or comments

In group discussions, the pupils generally coped well talking to a stranger in English.

Notes taken included the following:

•

“They are condent talking to a stranger and have ready understanding.”

•

“The pupils (…) were able to exchange personal information in a natural way.”

•

“They helped each other out well in English in discussion with the visitor.”

•

“A wide range of ability (…) all understood the visitor’s questions although he had to

repeat some.”

•

“Two pupils are very nervous but all are condent in presenting family and personal

information and all ask some questions.”

•

“Can reel off several (consecutive) sentences on personal information without

hesitation”.

In some classes pupils were encouraged to take some initiative in making statements or

offering comments. In a literacy class, pupils were expected to come to the front to make

statements of three sentences with gaps for the class to complete using the past tense

for example:

‘I… to the cinema with my friends.’

‘I… in a football team.’

‘Yesterday I… a beautiful dog.’

29

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Some pupils used examples with modals. For example: ‘I like to… I can… at the thing in

the sky’.

In a Year 5 literacy class:

“T returns the papers to the pupils. She asks them to look at each other’s work and say

why they think it is good.

On a sentence ‘In Dani’s concert everybody did the actions…’ a boy commented: ‘This

sentence is good because it has a capital letter, neat handwriting (etc)’.

Teacher gets Pupils involved in using language for practical classroom purposes including

giving instructions to each other. When one boy who has not done the illustrations for

homework tries to get away with doing them in class, the other pupils are expected to

tell him what he shouldn’t do. Therefore another boy told him: ‘Don’t draw pictures in

class, it was for homework’.

In a science class, most pupils were able (with support in some cases) to explain

concepts related to sound (‘volume; pitch’) and light (‘opaque, translucent’) and the

stronger ones were able to go beyond this. For example a boy volunteered to draw a

diagram to explain ‘angle of incidence’ and ‘angle of reection’. A girl could provide

substantial explanations without hesitation:

‘We know that light travels in straight lines because… behind the opaque object,

you cannot see the light, only the shadow. When you put a bottle or glass in front

of a source of light, the light travels through it.’

It is worth noting that the girl who provided the above comment has a rst language

which is neither Spanish nor English.

Some pupils were able to use English effectively in more exible situations, for example:

“(pupils contributing ideas from previous lesson) ‘nutrients pass through the

circulatory system; oxygen travels through our bodies and reaches every part.’”

“(Feedback from subgroup (two girls, one boy) on the desert as an ecosystem.) Pupils,

particularly the boy, managed sustained sentences without the need of notes. Pupils

helped each other out in a mature way using English.

Second subgroup (three girls) on the rainforest. Girls use a visual from a book, not

reading from it but talking about it. Pupils make a few slight errors, e.g. ‘support for

‘sustain’”.

Quality and accuracy of language

Although pupils’ capacity to communicate in a range of situations was the main focus

of observations, the quality and accuracy of the language used were also monitored.

It would be unfortunate if concern for accuracy were to inhibit pupils’ willingness to

communicate, but accuracy is needed if their linguistic resources are to be developed

further and they are to cope with more demanding situations.

30

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Pronunciation

(In a group interview) “Errors of pronunciation tended to focus on specic sounds such as

‘my job’. A frequent mistake was the ‘s’ and ‘sh’ sounds e.g. pronunciation of ‘shopping’.

Some specic sounds and intonation of about half the group make it harder for an English

native speaker to follow without a knowledge of Spanish”.

Certain combinations of consonants present difculties for Spanish-speakers. In one

class for example the uency of reading and accuracy of pronunciation, e.g. ‘clothes,

whole’, varied greatly. This kind of familiar difculty is reected in the pronunciation of the

past tenses in English, for example: ‘worked, honoured, walked (èd)’.

Although intonation is usually acceptable and does not often seriously impede

understanding, the stress can be misplaced, particularly on ‘technical words’, for example:

‘retina, transparent, miniscule’.

Vocabulary

In some respects, coping with general vocabulary was more of a problem than scientic

terms.

(In a group interview) “Some uncertainties, for example seeing ‘babies’ as synonymous

with ‘children’ (Question to interviewer: How many babies do you have?’).”

In another school, a boy who said ‘asignatura’ was immediately corrected by his peers.

The pupils interviewed could explain the game of handball to the visitor who did not know

the game, but none knew the word ‘goalkeeper’ in English, although all were enthusiastic

about football.

Syntax

“Pupils are asked to make two New Year resolutions each (one afrmative, one negative)

relevant to school or home. Examples:

‘I am going to: ‘behave in class’/‘study more’/ ‘help my mother at home’.’

‘I am not going to’: ‘play with my Playstation 2 all day’/‘eat so much chocolate’.”

“During the class reading of a story, the teacher interrupts occasionally to ask pupils at

random to put statements heard in the story into the negative, for example: ‘He wasn’t’,

‘she didn’t’ etc. Most pupils get these right but mistakes like ‘She not was…’ do occur.”

“Pupils were invited to ask questions which they do willingly, although the question forms

and word order are not always correct, for example ‘It has to be a glass bottle?’.”

(In group interviews) “Difculties in use of (past) tenses: four pupils were comfortable

using past tenses, three uncertain. (The tutor said afterwards that he was rather

concerned about their insecure use of tenses in unpredictable situations.).”

“(Apart from the boy with an English father) their grasp of tenses varies - tendency to use

the present for past and (perhaps more understandably) for the future.”

31

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

“(In a group interview in another school) All were secure in past tenses except for one boy

who said ‘last week I go’ (corrected immediately by his peers).”

Errors occurred in marking the past tense, for example, ‘injur(ed), escapèd’. In the

spoken language, these may be due to awed pronunciation (see above) rather than to

lack of grammatical knowledge.

Use of the denite article can be over-worked, for example:

‘I do the homework, the training.’ (past)

‘After the school I go.’ (future)

Pupils can be uncertain also about the choice of prepositions, for example:

“The teacher expects pupils to be precise. For example, a pupil offers ‘the camel has

a hump’.

The teacher prompts: ‘Where?’

A pupil rephrases: ‘The camel has a hump in the (sic) back’”. (Y5)

P: ‘S is going to explain you’ (sic).

P: ‘I go to play tennis at (name of town)’.

Conclusion: Pupils’ classroom performance in Primary 5&6

T

he lesson notes obtained for Study 1 focusing on the classroom performance

of pupils in Primary 6 reveal a good general participation in class and intellectual

engagement with subject matter, with no obvious observable evidence of pupils

falling behind or becoming alienated. Given that these are 11-year-old children,

there is a condent command of technical vocabulary in respect of several

different aspects of science, and also of English-language structure, revealing

an ability to produce extended utterances and not just single-word responses.

Pupils generally show ease of comprehension of their teacher’s spoken

utterances. The target language (English) indeed seems well-integrated into

the learning of both science and English, in keeping with the rst aim of the BEP.

There does not seem to be any obvious loss of learning of subject-matter as a

result of learning science through the medium of English.

Pupils were able to express a wide range of language functions which reect the

discourse of science lessons, e.g. giving reasons; giving explanations; dening

or exemplifying concepts or terms; expressing if-then relationships; describing

sequences of action; describing functions of organs or objects; describing what

things are like; expressing necessity; expressing how elements combine. There

are some errors in English language but these seem to be largely developmental

and are largely over-ridden by the positive things which pupils can already do

in English in their science lessons. When errors are made there is recurrent

evidence of helpful and corrective feedback being offered by other members of the

peer-group.

32

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

STUDY 2:

PRIMARY SCHOOL 5&6 GOOD PRACTICE IN CLASS

In Study 1, the focus was on what Year 5&6 pupils could do in class towards the end of

their primary school education. Study 2 draws on the same lessons but focuses on the

classroom practices which seemed associated with these pupil outcomes.

Introduction

Whole-class teaching was the predominant teaching style adopted, although there

were signicant exceptions. However, the predominance of the whole-class mode did

not necessarily mean that the teaching was narrowly ‘didactic’. Features of the most

effective teaching included: careful (short- and sometimes medium-term) planning,

a good rapport with pupils in an orderly but relaxed atmosphere, and an ability to spot

a key learning point and use it for the benet of the class as well as the individual.

Questions were well pitched to take account of the range of ability in the class and to

draw out answers from pupils’ underlying knowledge (particularly in science). There were

examples of paraphrase, analogy and visual material being used well for this purpose.

In science good use was made of simple visual aids, there was successful group

work based on thoughtful organization, and evidence of some differentiation in lesson

planning. In language & literacy, the teachers showed due concern for accuracy of

language, particularly where it affected meaning/understanding, but did not pursue

this concern in a way that inhibited or demoralised pupils when they were using English

willingly in class.

Lessons were usually well prepared with links to prior learning and with content

sequenced to deliver the objectives, although in about a third of lessons objectives

were implicit rather than explicit. Teacher’s explanations were clear and pupils

understood what they had to do. In about half the lessons progression could have

been strengthened and plans for the following lesson made more explicit.

Effective practice was reected in a number of ways: in the organisation of group work,

providing ‘hands on’ experience, the approach to prompting and correction, linking

language and content in teaching points, and the judicious use of Spanish to support, but

not replace, teaching through English.

The text types encountered by pupils were usually printed information texts. Recorded

audio or video texts were rarely encountered, so that the voices pupils heard were

predominantly the familiar ones of their own teachers.

Group work

There were examples of successful group work based on thoughtful organization.

In a science lesson, the composition of groups was drawn up by lots in order to produce

different mixed groups in each lesson. The investigative tasks for each group were

clear, the pupils knew the time available (8 minutes) to complete them for plenary

presentation, were allowed access to reference books and completed the tasks on time.

33

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

“Group 1 (2b, 2g)

Pupils have to take turns in joining up three elements on a board: scientic term,

denition, picture. A wired circuit (battery-powered) lights up when correct

connections are made between the elements. Pupils have to log their attempts and

successes so the teacher can check later how each is coping.

Examples of denitions:

‘The large part of your brain that helps you to move and remember’ (cerebrum)

‘The part of the brain below the cerebrum’ (cerebellum)”

Pupils are encouraged to discuss their work with each other provided they do so in

English. For example, in a language & literacy class, pupils asked questions in English to

clarify a mime on the Halloween theme to identify a character or book or lm such as ‘A

vampire’, ‘Ghost Busters’, ‘The Worst Witch’, ‘I Know What You Did Last Summer’.

In another class, the teacher read a summary of ‘The biography of Harriet Tubman’ twice

and then:

“Pupils are asked to note keywords only (it is meant to be comprehension, not

dictation) and then share notes in English with their group. Teacher circulates and

helps pupils to conate their ndings, getting them to complement their notes

with details spotted by others.

Notes from separate groups are combined and compared with those from the whole

class to build up a picture e.g.

‘… was married at age 24;’

‘1861-1865 – helped army of the North against the army from the South;’

‘(later) started a school for black children.’

Pupils showed a range of performance in note-taking – a demanding exercise for

pupils of this age. Their notes ranged from half a page to one sentence.”

In a Year 5 science class, work on vertebrates and invertebrates was consolidated rst by

groups presenting to the class through a spokesperson posters from a previous lesson

(e.g. Sponges: ‘they live in the rocks in the sea, they are not symmetrical, they lter

nutrients from the sediment…’), and then by further group work involving denitions

and classication:

“Group work shows evidence of: clear expectations, instructions well presented,

groups well organized. At each stage output from group work is checked and

reviewed with the class.

Read and match: Pupils have to match denition to ‘exoskeleton, arachnid’, etc.

Pupils have to work out whether particular animals are vertebrate or invertebrate

(‘panda, snake, dragony’, etc.).

Pupils have to classify groups of animals into proper category e.g. mammals,

reptiles, (in)vertebrates. (Some pupils not afraid to ask visitor in English for help).

34

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

Pupils have to choose an (in)vertebrate to describe to the class.

There is assessment of descriptions by teacher, trainee and peers.

Aggregated results for 4 activities for each team recorded on a grid.”

Notes: “A well organized lesson conducted at brisk pace, well managed to keep all pupils

involved. Teacher has presence, does not allow pupils’ concentration to become eroded,

pupils worked well together throughout. Pupils showed good understanding of content

and language. They speak with some condence, generally pronouncing clearly.

Teacher is rm, but pleasant. Has very good English and speaks naturally, but can model

it when accuracy needs improving. Appropriate content jointly planned with science

teacher who is present to help with group work.”

Hands-on experience

Good use was made of simple visual aids.

For example, a model of a skull was used with the ‘brain’ lifted out. The teacher explained

that the parts of the brain operate like a team, but there are some key players (parallel

made with football). Questions used simple examples to draw out understanding:

T: ‘Hypothalamus – it operates like a thermostat. Do have one at home?’

P: ‘Yes.’

T: ‘What does it do?’

P: ‘It (the hypothalamus)normally keeps the body temperature at 37°.’

T: ‘How small is the pituitary? Like a bean? P: Like a lentil. T: You’re getting very

close. Think of green. P: A pea.’

Science Year 5: “Literally a ‘hands-on’ lesson with the teacher providing samples of

material (e.g. leather, paper) for pupils to handle and examine. She gets pupils to work

out what ‘natural’ means in this context: they arrive at the provisional denition that

it means ‘material from animals or plants or out of the ground, whereas

‘manufactured’ materials, such as plastic, involve some kind of processing.’

For example, the teacher holds up some wool. A pupil suggests it is ‘cotton’. Teacher

says ‘No, it comes from a creature with four legs’. Several pupils chorus: ‘Sheep’.

Other pupils point out that ‘sheep are not green!’. Teacher replies the wool is dyed and

asks what the natural colour of wool is. Pupils offer white or grey. The teacher has high

expectations reected in nuances of meaning and suggests e.g. ‘whitish, greyish’.

The teacher then asks ‘Who can tell me which objects around the classroom are made

from natural materials? Pupils produce a book (Q – ‘Is it all natural? – what about the

spiral-binding?’), and pin board (cork)’.

The same process is repeated more quickly identifying ‘manufactured materials’ around

the room. This leads on to further discussion of materials, such as ‘pencil sharpeners’,

which are made out of more than one material.

35

BEP. EVALUATION REPORT

In a recap at the end of the lesson, the denition is agreed that ‘natural materials are

from animals, plants, or from the ground and manufactured materials are made by

humans processing natural materials’”.

In another school, pupils were motivated by a Year 5 lesson on the ‘circulatory system’

which involved a ‘doctor’ taking the pulse rate of various ‘patients’ before and after they

had been sent for a run. A table of results from different ‘patients’ was then drawn up and

discussed.

Linking language and content

Pupils’ progress was enhanced where the teacher provided them with a stimulus to offer

more sophisticated and accurate language.

Science Year 6: “The teacher asks for repetition for reinforcement, and moves forward

pupils’ utterances by encouraging the use of additional language, particularly adverbs or

adverbial phrases e.g. ‘more often, so much, better’”.

Language & literacy Year 5: “The teacher shows pupils pictures and pupils have to offer

a sentence on each one. Her expectations are high and she expects them to lengthen

sentences by adding (say) adjectives or adverbial phrases where they can, for example:

‘The camel is walking in the hot desert in the afternoon’”.

Science Year 5: “The teacher supports her commentary on the experiment with cue-

cards of key language. She draws attention to the importance of verbs which are colour-

coded differently from nouns”.

Science Year 5: “The teacher is keen for pupils to retain specialist vocabulary and refers

to ‘The Flintstones’ as a mnemonic for ‘int’”.

Language & literacy Year 5: “The teacher makes a point of choosing words for tests

and reinforcement from material covered in the past week in language & literacy and

science. The tests require a demanding level of understanding of English grammar

(e.g. verbs: ‘burn, bring, bend, build’ etc) and vocabulary (‘sticky, congratulations,

delighted, evidence’ etc).”

Language & literacy Year 5: “Sentences are pooled by the class on the board and teacher

draws out grammar points focusing on the present continuous, such as ‘sit/sitting; put/

putting; touch/touching’. Teacher plays close attention to spelling and pronunciation,

for example ‘talking/ walking’”.

Science Year 5: “The teacher prompts the class about an experiment about chemical

change simply by asking ‘next?’, ‘nally’ etc. and only offers the answer if the pupil is

stuck. A girl commented ‘Finally the gas goes up into the balloon and… (teacher)... the

balloon inates’”.

In a lesson about reviewing work on the digestive system, the teacher used sustained

probing to check understanding of the topic and the pupils’ grasp of language to talk