New Tricks for an Old Measure: The Development of the Barratt

Impulsiveness Scale–Brief (BIS-Brief)

Lynne Steinberg and Carla Sharp

University of Houston

Matthew S. Stanford

Baylor University

Andra Teten Tharp

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia

The Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS), a 30-item self-report measure, is one of the most commonly used

scales for the assessment of the personality construct of impulsiveness. It has recently marked 50 years

of use in research and clinical settings. The current BIS-11 is held to measure 3 theoretical subtraits,

namely, attentional, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness. We evaluated the factor structure of the BIS

using full information item bifactor analysis for Likert-type items. We found no evidence supporting the

3-factor model. In fact, half of the items do not share any relation with other items and do not form any

factor. In light of this, we introduce a unidimensional Barratt Impulsiveness Scale–Brief (BIS-Brief) that

includes 8 of the original BIS-11 items. Next, we present evidence of construct validity comparing scores

obtained with the BIS-Brief against the original BIS total scores using data from (a) a community sample

of borderline personality patients and normal controls, (b) a forensic sample, and (c) an inpatient sample

of young adults and adolescents. We demonstrated similar indices of construct validity that is observed

for the BIS-11 total score with the BIS-Brief score. Use of the BIS-Brief in clinical assessment settings

and large epidemiological studies of psychiatric disorders will reduce the burden on respondents without

loss of information.

Keywords: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, item response theory, assessment

The construct of impulsiveness is broadly defined as “a predis-

position toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external

stimuli without regard to the negative consequences of these

reactions to the impulsive individuals or to others” (Moeller,

Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz, & Swann, 2001, p. 1784). Impulsive-

ness has been a focus of great interest both in the personality and

clinical psychology literature due to its relevance for occupational

and educational outcomes, as well as a wide range of psychiatric

disorders, including substance use disorders (de Wit, 2009), anti-

social behavior (Barratt, Stanford, Kent, & Felthous, 1997), bor-

derline personality disorder (BPD; Links, Heslegrave, & van Ree-

kum, 1999), intermittent explosive disorder (Brady, Myrick, &

McElroy, 1998), pathological gambling (Blaszczynski & Nower,

2002), bipolar disorder (Swann, Steinberg, Lijffijt, & Moeller,

2008), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and conduct prob-

lems in children (Nigg, 2003).

One of the most well-known and most used measures of impul-

siveness is the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS; Barratt, 1959).

The BIS, currently in its 11th revision (Patton, Stanford, & Barratt,

1995), is a 30-item self-report instrument designed to assess the

personality/behavioral construct of impulsiveness. In 2009, the

BIS celebrated its 50th anniversary, and by March 2009, 551

citations of the BIS-11 were recorded (Stanford et al., 2009),

building on the large number of publications using the preceding

versions of the instrument.

Given its widespread use, the BIS has been highly influential for

contemporary conceptualizations of impulsivity in personality and

clinical literature. Like many personality constructs, there has been

disagreement about the exact number of subtraits of impulsiveness,

ranging from two (Reynolds, Ortengren, Richards, & de Wit,

2006) to as many as five subtraits (Meda et al., 2009). Barratt’s

conceptualization of impulsiveness as described in the BIS

(Version 10) includes the theoretical subtraits of Cognitive Impul-

siveness, Motor Impulsiveness, and Non-Planning Impulsiveness

(Barratt, 1985). More recently, Patton et al. (1995) conducted a

second-order factor analysis and demonstrated the three-

component trait structure. Within this three-component conceptu-

alization, Cognitive Impulsiveness refers to the tendency to make

quick decisions, Motor Impulsiveness refers to a tendency to act

without thinking, and Non-Planning Impulsiveness refers to a lack

of “futuring” or forethought (Barratt, 1985). This conceptualiza-

tion of impulsiveness is in line with most empirical research to

date (Lejeuz, Magisdson, Mitchell, Stevens, & de Wit, 2010),

which have consistently conceptualized impulsiveness to include

This article was published Online First November 12, 2012.

Lynne Steinberg and Carla Sharp, Department of Psychology, Univer-

sity of Houston; Matthew S. Stanford, Department of Psychology and

Neuroscience, Baylor University; Andra Teten Tharp, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and

do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lynne

Steinberg, Department of Psychology, 126 Heyne Building, University of

Psychological Assessment © 2012 American Psychological Association

2013, Vol. 25, No. 1, 216 –226 1040-3590/13/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0030550

216

diminished ability to focus on tasks (i.e., attentional impulsive-

ness) and/or persist in tasks (i.e., motor impulsiveness); a tendency

to act on the spur of the moment and poor future planning (i.e.,

non-planning impulsiveness; Patton et al., 1995; Whiteside &

Lynam, 2001); diminished ability to delay gratification or height-

ened discounting of reward as a function of delay as well as hypo-

and hypersensitivity to reward and punishment (Ainslie, 1975;

Gray, 1987); poor response inhibition and increased passive avoid-

ance (Logan, 1994); and diminished ability to regulate emotion,

sometimes referred to as “urgency” (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001).

Despite the above support for Barratt’s three-factor model, the

factor structure of the BIS was determined decades ago using

traditional factor analysis. Few studies since the original validation

of the BIS-11 have explicitly examined its factor structure and

psychometric properties. For example, Spinella (2007) conducted

a principal-component factor analysis with orthogonal rotation and

selected five items with the highest loadings on each of the three

established factors resulting in a 15-item version. Ireland and

Archer (2008) performed both confirmatory and principal-

component factor analysis to evaluate the factor structure of the

BIS-11. As was the case for the earlier factor analytic studies, the

analyses done in these studies used Pearson correlations, which

can result in spurious factors arising from differences in endorse-

ment of item response categories (often named “difficulty” factors

in educational measurement). However, to our knowledge, no

studies to date have examined the factor structure and individual

item performance of the BIS using current full information ap-

proaches appropriate for categorical item responses.

Against this background, the first aim of the present study was

to examine the established three-factor structure of the BIS

through a confirmatory multidimensional item response theory

(IRT) approach. Past research (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2008) suggests

that IRT item analysis of lengthy measures results in a reduction of

the number of items via a selection of items with optimal charac-

teristics; reliability may be even increased using fewer items (e.g.,

Steinberg & Thissen, 1996). This is advantageous for the use of the

BIS in large-scale epidemiological studies of psychiatric disorders

and for reducing the burden on respondents in clinical assessment

settings. In anticipation of the shortening of the BIS, our second

aim was to evaluate the construct validity of the new shorter BIS

by examining its performance against the original 30-item BIS-11

version in three samples: (a) an adult community sample of indi-

viduals meeting criteria for BPD and normal controls (King-Casas

et al., 2008; Patel, Sharp, & Fonagy, 2011), (b) an adult sample of

individuals who have engaged in domestic violence (Stanford,

Houston, & Baldridge, 2008), and (c) an adolescent and young

adult inpatient sample (Sharp, Ha, & Fonagy, 2011). We organize

the above two aims in two studies. Study 1 is an IRT study of the

BIS to examine its factor structure and item parameters, and Study

2 is a construct validity study of the shortened BIS.

Study 1: Measurement Models

The methods of IRT were used to evaluate the factor structure of

the 30-item BIS-11. The IRT model fitting and the computation of

the test statistics were performed using a beta version of IRTPRO

(Cai, du Toit, & Thissen, 2011; Thissen, 2009). Goodness of fit of

the IRT models was evaluated using the M

2

statistics and its

associated root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA)

value (Cai, Maydeu-Olivares, Coffman, & Thissen, 2006;

Maydeu-Olivares & Joe, 2005; Maydeu-Olivares & Joe, 2006;

Thissen, 2009), and the standardized local dependence (LD) chi-

square statistics (based on the LD statistic proposed by Chen &

Thissen, 1997). The graded response model (Samejima, 1969,

1997) was selected as the item response model for these analyses;

the graded model has often been found useful for questionnaire

data collected using Likert-type scales (for examples, see Fraley,

Waller, & Brennan, 2000; Gray-Little, Williams, & Hancock,

1997; Steinberg, 1994; Steinberg, 2001; Steinberg & Thissen,

1996).

Method

Participants. Undergraduate students at a midsized private

Southern university (N ⫽ 1,178; female 77.4%, male 22.6%; mean

age ⫽ 19.4, SD ⫽ 1.1; classification: freshman ⫽ 46.1%, sopho-

more ⫽ 23.5%, junior ⫽ 14.9%, and senior ⫽ 15.4%) were

recruited via a departmental research website accessible by all

undergraduate psychology majors. Among participants, 61.2%

were Caucasian, 12.8% were Hispanic, 12.8% were Asian/Pacific

Islander, 8.8% were African American, and 4.4% self-identified as

“other” or were multiracial. Students were given extra credit in a

course for completion of the BIS-11. These data were collected

with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.

Measures

The BIS-11 (Patton et al., 1995; Stanford et al., 2009). The

BIS-11 is a 30-item self-report measure designed to assess general

impulsiveness. The items are scored on a 4-point scale (1 ⫽

rarely/never,2⫽ occasionally,3⫽ often,4⫽ almost always/

always). Published reliability coefficients for the BIS-11 total

score (Cronbach’s ␣) range from 0.72 to 0.83.

Results

Evaluating the factor structure of the 30-item BIS-11.

Multidimensional model. Patton et al. (1995) investigated the

factor structure of the BIS-11 using principal components of

Pearson correlations with oblique rotation. Their analysis included

a second-order factor structure with three second-order factors that

were labeled attentional, non-planning, and motor impulsiveness.

Stanford et al. (2009) noted increased interest in the usefulness of

these subscales to explore relationships of impulsiveness with

other clinical symptoms. Our first analysis evaluating the factor

structure of the BIS-11 is designed to mirror the Patton et al.

structure using contemporary methods of full information bifactor

analysis.

Item bifactor analysis refers to a type of confirmatory multidi-

mensional IRT model in which one general factor and one or more

specific factors are specified (Cai, Yang, & Hansen, 2011). A

second-order factor is a constrained bifactor model (Yung,

McLeod, & Thissen, 1999); the second-order factor model adds

proportionality constraints within items across factors (Thissen &

Steinberg, 2010). Table 1 presents the IRT slope parameters and

standard errors for the full information item bifactor model. In this

analysis, one general factor (all 30 items) and three specific factors

(Attentional, Non-planning, and Motor Impulsiveness subscales)

217

BARRATT IMPULSIVENESS SCALE–BRIEF

are modeled. In IRT, slope parameters are algebraically related to

factor loadings and represent the degree of relation to the under-

lying construct; slopes that are 1 or greater are considered sub-

stantial. The column labeled a

1

is the general factor that includes

all 30 items. The columns a

2

, a

3

, and a

4

include the items for

attentional, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness as described in

Patton et al., respectively. (Note, the column labeled a lists the

slope parameters for a subsequent analysis that is described later.)

A perusal of the column for the general factor (a

1

) shows that only

about half of the items have substantial slope parameters. For

example, Item 19 “I act on the spur of the moment” has a

substantial slope parameter of 1.89; Item 15 “I like to think about

complex problems” has a low slope parameter of 0.47. This pattern

of item parameters implies that the responses to about half of the

items are not strongly related to what the general impulsiveness

factor measures.

The specific factors, a

2

–a

4

, reveal a different pattern of item

slope parameters. Each specific factor represents what has been

termed a “doublet” in the psychological measurement literature

and can be described as LD. LD occurs when items are more

strongly correlated than can be accounted for by the underlying

construct; in fact, the correlation may not represent a construct

intended to be measured by the item set. For example, the two

items comprising the content of a

2

, attentional impulsiveness, Item

28 “I am restless at the theater or lectures” and Item 11 “I ‘squirm’

at plays or lectures,” are similar in wording and meaning. The LD

is most likely a result of item similarity. These two items are the

only ones to show substantial slope parameters on that specific

factor; thus, this is not the attention construct intended for mea-

surement with the eight-item set, but rather excess covariation that

cannot be accounted for by the general factor. Similarly, the

specific factor “motor” impulsiveness (a

3

) is defined by LD be

-

tween the items, “I act on the spur of the moment” and “I act on

impulse”; the specific factor “non-planning” impulsiveness (a

4

)is

defined by LD between “I get easily bored when solving thought

problems” and “I like to think about complex problems.”

Table 1

Slope Parameter Estimates and Standard Errors for the Bifactor and Unidimensional IRT Models

Bifactor model

Unidimensional

model

Item Content a

1

SE a

2

SE a

3

SE a

4

SE a SE

11 I “squirm” at plays or lectures. 1.00 0.17 3.41 0.40 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.73 0.07

28 I am restless at the theater or

lectures.

1.02 0.15 2.99 0.29 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.78 0.07

6 I have “racing” thoughts. 0.43 0.06 0.57 0.07 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.60 0.06

5 I don’t pay attention. 1.12 0.08 0.56 0.07 0.0 — 0.0 — 1.20 0.08

9 I concentrate easily. 1.63 0.10 0.51 0.08 0.0 — 0.0 — 1.52 0.09

26 I often have extraneous thoughts

when thinking.

0.31 0.06 0.49 0.07 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.46 0.06

24 I change hobbies. 0.36 0.06 0.40 0.07 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.50 0.06

20 I am a steady thinker. 1.77 0.11 0.09 0.08 0.0 — 0.0 — 1.55 0.10

19 I act on the spur of the moment. 1.89 0.23 0.0 — 3.10 0.41 0.0 — 1.37 0.09

17 I act “on impulse.” 1.79 0.16 0.0 — 2.50 0.23 0.0 — 1.47 0.09

2 I do things without thinking. 1.33 0.09 0.0 — 0.81 0.09 0.0 — 1.45 0.09

3 I make up my mind quickly. ⫺0.14 0.06 0.0 — 0.66 0.08 0.0 — 0.05 0.06

4 I am happy-go-lucky. ⫺0.00 0.06 0.0 — 0.54 0.07 0.0 — 0.11 0.06

22 I buy things on impulse. 0.78 0.07 0.0 — 0.53 0.07 0.0 — 0.92 0.07

16 I change jobs. 0.25 0.07 0.0 — 0.36 0.08 0.0 — 0.38 0.07

21 I change residences. 0.13 0.06 0.0 — 0.15 0.07 0.0 — 0.20 0.06

25 I spend or charge more than I

earn.

0.77 0.07 0.0 — 0.13 0.07 0.0 — 0.80 0.07

30 I am future oriented. 0.85 0.07 0.0 — ⫺0.08 0.07 0.0 — 0.74 0.07

23 I can only think of one thing at a

time.

0.15 0.06 0.0 — ⫺0.21 0.07 0.0 — 0.13 0.06

18 I get easily bored when solving

thought problems.

1.09 0.15 0.0 — 0.0 — 1.52 0.22 0.79 0.07

15 I like to think about complex

problems.

0.76 0.08 0.0 — 0.0 — 1.11 0.19 0.47 0.06

29 I like puzzles. 0.45 0.07 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.72 0.10 0.32 0.06

12 I am a careful thinker. 1.87 0.11 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.14 0.13 1.59 0.10

27 I am more interested in the present

than the future.

0.39 0.06 0.0 — 0.0 — 0.04 0.08 0.45 0.06

14 I say things without thinking. 0.91 0.07 0.0 — 0.0 — ⫺0.02 0.09 1.11 0.08

10 I save regularly. 0.97 0.07 0.0 — 0.0 — ⫺0.12 0.09 0.89 0.07

13 I plan for job security. 1.11 0.08 0.0 — 0.0 — ⫺0.30 0.10 0.95 0.07

8 I am self-controlled. 1.42 0.09 0.0 — 0.0 — ⫺0.34 0.10 1.25 0.08

7 I plan trips well ahead of time. 1.23 0.09 0.0 — 0.0 — ⫺0.54 0.13 1.06 0.07

1 I plan tasks carefully. 1.67 0.11 0.0 — 0.0 — ⫺0.59 0.16 1.38 0.09

Note. IRT ⫽ item response theory. Boldface values indicate slope parameter values of 0.9 or higher. Dashes indicate that there are no standard errors for

fixed parameters.

218

STEINBERG, SHARP, STANFORD, AND THARP

The analysis using the bifactor model shows 14 additional pairs

of items with substantial LD (values 10 or greater are considered

noteworthy). The standardized LD chi-square statistics imply that

the bifactor model is not adequate to account for the excess

covariation between these item pairs.

The full information bifactor factor analysis conducted to eval-

uate the Patton et al. (1995) structure of the 30-item BIS-11

indicated that the pattern of item covariation is multidimensional.

However, the pattern of the slope parameters for the specific

factors shows a type of multidimensionality reflective of consis-

tency among item responses that is more LD than reflective of

individual differences on the intended constructs.

Unidimensional models. Because the bifactor model showed

that more than half of the items did not have a substantial relation

to the general underlying construct and that many of the items

show LD, we now aim to develop a shorter unidimensional version

of the BIS. The next IRT analysis takes a step back and investi-

gates the magnitude of the item slope parameters specifying a

unidimensional model. The motivation for this analysis is to select

the items that show substantial slope parameters for possible

inclusion in the brief BIS instrument. The two rightmost columns

of Table 1 lists the slope parameters and their associated standard

errors for the 30 BIS-11 items for the unidimensional model.

Again, more than half of the items do not show a substantial

relation to the underlying construct, and there are 19 pairs of items

that show LD; the standardized chi-square values range from 10 to

161. The substantial LD values indicate that a unidimensional

model is not adequate to account for the item covariation. Next, we

evaluated a unidimensional model that includes the 13 of the

BIS-11 items that showed substantial slope parameters in the

30-item unidimensional model analysis.

The graded model item parameters are presented in Table 2. The

slope parameters, representing the degree of relation of the item

response to the underlying construct as defined by the 13 BIS

items, shows substantial slopes for all items except Item 22 (“I buy

things on impulse”). However, four item pairs exhibit substantial

LD (the standardized chi-square values are 10.6, 12.4, 12.7, and

68.4). At this stage of the development of the brief version of the

BIS, we selected one item of the item pair 17 and 19 that exhibited

the largest LD index for omission (Item 17, “I act on impulse”).

With such a small item set, we focused on item content in addition

to item parameters to guide item selection. We omitted four

additional items for the following reasons: (a) Item 22 (“I buy

things on impulse”) has a low slope parameter, (b) Items 20 (“I am

a steady thinker”) and 13 (“I plan for job security”) may now have

different meaning today than when these items were written in the

1960s (e.g., the meaning of “steady thinker” is not clear, planning

for job security in the present global economy may not be possi-

ble), and (c) Item 7 (“I plan trips well ahead of time”) assumes the

respondent takes trips.

Development of the BIS-Brief. Our focus at this stage is to

evaluate the remaining eight items for inclusion in the new BIS-

Brief instrument. We are interested in developing a unidimensional

impulsiveness measure with items that have substantial slope

parameters and an adequate range of threshold parameters. Table

3 presents the slope and threshold parameter estimates for the eight

items. The graded IRT model showed satisfactory fit, M

2

(244) ⫽

706.12, p ⬍ .001; RMSEA ⫽ 0.04; however, there was one

noteworthy LD index for the item pair “I don’t pay attention” and

“I concentrate easily” (standardized

2

LD index ⫽ 10.4). An

analysis was done to evaluate the significance of the LD. Specif-

ically, a bifactor model that includes an equal-slope second factor

composed of the item pair (Items 5 and 9) that showed LD was

used. The estimated slope parameter for the specific factor is 1.14

with a standard error of 0.13. To evaluate the significance of the

LD, a likelihood ratio chi-square goodness-of-fit difference test

was used. The –2 log-likelihood obtained in the bifactor analysis

was subtracted from the –2 log-likelihood obtained in the eight-

item unidimensional analysis. The result is G

2

(1) ⫽ 12.5, p ⬍

.001. In practice, possible ways to deal with significant LD include

either (a) omitting one of the items in the pair or (b) forming a

testlet (Steinberg & Thissen, 1996; Thissen & Steinberg, 2010)of

the item pair by summing the item responses, thereby creating a

single “super” item. The testlet is then used for item parameter

estimation (so that the slope parameters are not influenced by the

excess covariation between the two items showing LD).

We opted for inclusion of the six items and the testlet compris-

ing Items 5 and 9 so that all eight items can be retained for the new

BIS-Brief measure. Table 4 lists the item parameters for the now

seven-item analysis (six items, one testlet). Because the testlet is

made from the sum of the two items, total scores can be calculated

by summing up the responses to the eight items. Thus, the testlet

Table 2

Graded Model Item Parameter Estimates for 13 BIS-11 Items

Item Brief content aSE b

1

SE b

2

SE b

3

SE

1 Plan tasks 1.55 0.10 ⫺1.01 0.07 0.58 0.06 2.75 0.15

2 Do things 1.57 0.10 ⫺0.67 0.06 1.58 0.09 3.23 0.20

5 Don’t pay attention 1.07 0.08 ⫺0.87 0.09 1.73 0.12 3.78 0.28

7 Plan trips 1.15 0.08 ⫺1.06 0.09 0.54 0.07 2.21 0.14

8 Self-controlled 1.35 0.09 ⫺0.40 0.06 1.57 0.10 3.45 0.23

9 Concentrate easily 1.38 0.09 ⫺1.76 0.11 0.16 0.05 1.96 0.11

12 Careful thinker 1.65 0.10 ⫺0.81 0.06 0.99 0.06 3.08 0.18

13 Plan for job security 1.01 0.07 ⫺0.92 0.09 0.69 0.08 2.26 0.16

14 Say things 1.10 0.08 ⫺1.15 0.10 1.49 0.11 3.27 0.23

17 Act on impulse 1.49 0.10 ⫺1.04 0.07 1.16 0.07 2.79 0.16

19 Spur of moment 1.40 0.09 ⫺1.54 0.10 0.95 0.07 2.61 0.15

20 Steady thinker 1.59 0.10 ⫺1.40 0.09 0.63 0.06 2.79 0.16

22 Buy on impulse 0.78 0.07 ⫺1.82 0.17 0.97 0.11 3.29 0.28

Note. BIS-11 ⫽ Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11.

219

BARRATT IMPULSIVENESS SCALE–BRIEF

accounts for the LD in the item analysis without altering the

calculation of the summed score.

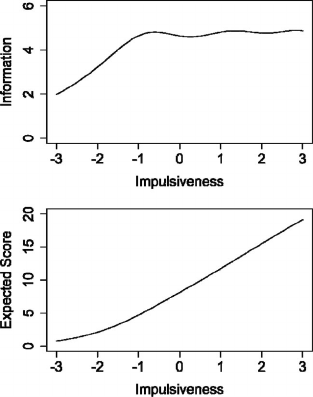

The test information curve is shown in the upper panel of Figure

1. Test information curves show how well the construct is mea-

sured at all levels of the underlying construct continuum. Mea-

surement precision is approximately constant for values of the

construct continuum between –1 and ⫹ 3. Total information for

the eight BIS items is approximately 5 for this range of the

continuum. The standard errors of IRT scores for this range are

approximately

1

兹

5

⫽ 0.45; this translates to an IRT approxima-

tion of reliability of .80 (calculated as one minus measurement

variance) for the eight-item BIS-Brief scores in that range. For

comparison, the traditional reliability estimates using Cronbach’s

alpha for the 30-item BIS-11 and the eight-item BIS-Brief scores

are .83 and .78, respectively. The lower panel of Figure 1 presents

the expected score curve (also known as the test characteristic

curve). This curve shows the expected summed score for each

value of the underlying construct continuum. The curve is linear

for values of impulsiveness on the continuum between ⫺2 and ⫹3;

this implies that the traditional summed score is a good approxi-

mation of the IRT scale score.

Using the methods of IRT, we have developed an eight-item

brief version of the BIS. The next step is to investigate evidence of

construct validity. In Study 2, we evaluated whether scores ob-

tained on the brief version replicate group differences and patterns

of correlations with other psychological constructs that have been

previously found with the 30-item BIS-11 scores.

Study 2: Construct Validation

The construct validity of scores obtained on the BIS-Brief

was investigated using constructs that have been theoretically

and empirically linked with impulsiveness. First, we examined

the capacity of the BIS-Brief to distinguish between female

adults with and without BPD. BPD is a severe mental health

condition characterized by deficits in multiple areas of func-

tioning in the cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains. The

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth

edition, text revision (DSM–IV–TR; American Psychiatric

Association, 2000) requires that five out of nine clinical

symptoms are present for a full diagnosis of BPD, of which one

criteria specifically refers to impulsiveness: impulsivity in at

least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (e.g., spend-

ing, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating). A

large number of empirical studies have demonstrated the rela-

tion between borderline traits and impulsivity (Skodol, Gunder-

son, et al., 2002; Skodol, Siever, et al., 2002). We evaluated

whether the BIS-Brief would perform as well as the full BIS-11

in distinguishing patients diagnosed with BPD from normal

controls.

Next, we examined the relation between the BIS-Brief and

aggression-related constructs with data obtained in two separate

samples. Aggressive individuals, and particularly those charac-

terized as impulsively aggressive, have been shown to have

higher scores on personality measures of impulsiveness (Hous-

ton & Stanford, 2005). On this basis, we expected a positive

correlation between the new BIS-Brief and the Impulsive sub-

scale (but not the Premeditated subscale) of the Impulsive

Premeditated Aggression Scale (IPAS; Stanford et al., 2003).

We also expected a positive correlation with anger, hostility,

and aggression as measured by the Buss-Perry Aggression

Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992). All of the data

reported in Study 2 had IRB approval from the respective

universities conducting the data collection.

Table 3

Graded Model Item Parameter Estimates for the Eight BIS-11 Items

Item Content aSE b

1

SE b

2

SE b

3

SE

1 I plan tasks carefully. 1.38 0.09 ⫺1.07 0.08 0.62 0.06 2.96 0.19

2 I do things without thinking. 1.59 0.12 ⫺0.66 0.06 1.58 0.09 3.21 0.21

5 I don’t “pay attention.” 1.17 0.09 ⫺0.82 0.08 1.63 0.11 3.55 0.25

8 I am self-controlled. 1.47 0.10 ⫺0.38 0.06 1.51 0.09 3.29 0.22

9 I concentrate easily. 1.44 0.10 ⫺1.72 0.11 0.16 0.05 1.92 0.11

12 I am a careful thinker. 1.66 0.11 ⫺0.81 0.06 1.00 0.07 3.09 0.19

14 I say things without thinking. 1.15 0.09 ⫺1.12 0.09 1.46 0.11 3.18 0.22

19 I act on the spur of the moment. 1.13 0.09 ⫺1.76 0.13 1.08 0.09 3.01 0.21

Note. BIS-11 ⫽ Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11.

Table 4

Graded Model Item Parameter Estimates for the BIS-Brief Items, Using a Testlet Combining Items 5 and 9

Item Brief content aSE b

1

SE b

2

SE b

3

SE b

4

SE b

5

SE b

6

SE

1 Plan tasks 1.40 0.10 ⫺1.06 0.08 0.61 0.06 2.93 0.18

2 Do things 1.71 0.12 ⫺0.64 0.06 1.52 0.09 3.08 0.19

8 Self-controlled 1.41 0.10 ⫺0.39 0.06 1.54 0.10 3.36 0.23

12 Careful thinker 1.67 0.12 ⫺0.80 0.06 1.00 0.07 3.08 0.19

14 Say things 1.19 0.09 ⫺1.09 0.09 1.42 0.10 3.10 0.21

19 Spur of moment 1.18 0.09 ⫺1.71 0.12 1.05 0.08 2.92 0.20

5 & 9 Testlet5plus9 1.38 0.09 ⫺2.21 0.13 ⫺0.87 0.07 0.27 0.06 1.47 0.09 2.42 0.14 3.77 0.26

Note. BIS-Brief ⫽ brief version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.

220

STEINBERG, SHARP, STANFORD, AND THARP

Participants

Adult community sample: Borderline versus normal

controls. Participants (N ⫽ 236) were recruited as part of a

larger study evaluating behavioral and neural correlates of social

exchange among healthy controls and individuals diagnosed with

BPD (King-Casas et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2011). Participants were

women from an urban Southwestern city recruited by newspaper

advertisements and pamphlets seeking participants for a study of

individuals with past and current difficulties with intense emo-

tions, relationships, and impulsivity. Of the full sample, n ⫽ 68

(28.8%) met criteria for BPD, whereas n ⫽ 128 (54.2%) were free

of both Axis I (determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for

DSM Disorders; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) and

Axis II disorders (determined by the Diagnostic Interview Sched-

ule for DSM–IV Personality Disorders; DIPD; Zanarini, Franken-

burg, Sickel, & Yong, 1996).

Participants had a mean age of 31.27 years (SD ⫽ 9.8; range ⫽

18 – 63 years). They were primarily Caucasian (46.6%), with a

wide distribution among Black American (19.5%), Hispanic

(19.1%), Asian American (8.9%), and those of mixed race (2.5%);

43.2% of participants reported low annual income (below

$20,000), and 43.6% had never been married.

Adult domestic violence sample. Participants (N ⫽ 111)

were men recently convicted of domestic violence in two south-

eastern Louisiana parishes. Individuals convicted of domestic vi-

olence in these two parishes are court-ordered to attend a state-

approved intervention program as part of sentencing. Recruitment

for the present study occurred during the program’s initial intake

assessment over the course of 12 months. As part of the intake

procedure, participants were asked to participate in the study by

anonymously completing a packet of self-report questionnaires.

The packets were completed at home and returned during the next

appointment. All participants given packets during this time period

returned the packets at least partially completed. Participants had

a mean age of 34.56 years (SD ⫽ 10.87; range ⫽ 18 –71 years).

Adolescent and young adult inpatient sample. The sample

included 92 inpatients in the Adolescent and Young Adult Treat-

ment Programs of a private tertiary care inpatient treatment facility

specializing in the evaluation and stabilization of patients who

failed to respond to previous interventions. All patients on the units

were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria included active psy-

chosis, IQ ⬍ 70, diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, and for

primary language not being English.

Respondents were between the ages of 13 and 22 (mean age ⫽

16.72; SD ⫽ 2.36). All patients received a comprehensive psychi-

atric evaluation at intake. The modal number of diagnoses was

two, and the average number of diagnoses was between two and

three.

Measures

Adult community sample: Borderline versus normal

controls. The Diagnostic Interview for DSM–IV Personality

Disorders–Borderline Scale (DIPD-BPD; Zanarini et al., 1996)is

a semistructured interview used to diagnose Axis II disorders. The

DIPD-BPD consists of nine items corresponding with DSM–IV

criteria rated as 0 (Not present),1(Possibly present), or 2 (Defi-

nitely present). Five ratings of 2 are necessary to meet criteria for

BPD. The DIPD-BPD has been shown to be a reliable and stable

measure of BPD and has demonstrated strong concurrent validity

(Zanarini et al., 1996, 2003). All interviews were video-recorded

with permission from study participants. To determine each rater’s

agreement with the original diagnostic classification, the video

recordings of 19 participants (17% of the total sample) were

viewed and coded by two trained and independent raters blind to

the group status of participants. Kappa was .88 (p ⬍ .001) for the

first rater, indicating near perfect agreement, and .79 (p ⬍ .001) for

the second rater, indicating substantial agreement (Landis & Koch,

1977). Cronbach’s alpha for the nine items was .89 in the present

sample.

Adult domestic violence sample. Measures included in this

study relevant for the evaluation of the BIS-Brief were the Per-

sonality Assessment Inventory-Borderline subscale (PAI-BOR),

the PAI-Anti-Social subscale (PAI-ANT), the PAI-Aggressive

subscale (PAI-AGG), and the BPAQ (Buss & Perry, 1992).

The PAI (Morey, 1991) includes 344 four-point Likert scale

questions. In addition to assessing the presence of Axis I condi-

tions, it assesses features of paranoid, schizotypal, schizoid, bor-

derline, and antisocial personality disorders. It also includes va-

lidity scales and scales to assist in treatment. The PAI was normed

on a sample of over 3,500 individuals from community, college,

and clinical settings, and internal consistency estimates range from

.75 to .79 for individual scales (Morey, 1991). The PAI-BOR and

the PAI-ANT are two subscales of the PAI that assess symptoms

of personality disorder. The PAI-BOR, in particular, has demon-

strated good internal consistency (Morey, 1991) and construct

validity (Jacobo, Blais, Baity, & Harley, 2007; Kurtz, Morey, &

Tomarken, 1993). Similarly, the PAI-ANT has demonstrated good

internal consistency in the original validation study of the PAI

(Morey, 1991) and strong correlations with the Minnesota Multi-

phasic Personality Inventory scale for antisocial personality disor-

der (Morey, Waugh, & Blashfield, 1985) and the Psychopathy

Figure 1. Upper panel: Test information curve for the Barrat Impulsive-

ness Scale-Brief (BIS-Brief) showing how well the construct is measured

at all levels of the underlying construct continuum. Lower panel: Expected

score curve for the BIS-Brief showing the expected summed score for each

value of the construct continuum.

221

BARRATT IMPULSIVENESS SCALE–BRIEF

Checklist Revised total score (Loranger, Susman, Oldham, &

Russakoff, 1987). The PAI-AGG is a treatment consideration

subscale of the PAI and provides an indicator of potential treat-

ment complications for the clinician using the PAI. The PAI-AGG

has demonstrated good internal consistency and concurrent valid-

ity with the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (Morey,

1991).

The BPAQ is a 29-item measure that contains four subscales:

Verbal Aggression (five items; e.g., “My friends say that I’m

somewhat argumentative”; Cronbach’s ␣⫽.80), Physical Aggres-

sion (nine items; e.g., “I get into fights a little more than the

average person”; Cronbach’s ␣⫽.84), Anger (seven items; e.g., “I

have trouble controlling my temper”; Cronbach’s ␣⫽.76), and

Hostility (eight items; e.g., “I am suspicious of overly friendly

strangers”; Cronbach’s ␣⫽.83). Participants responded to items

on a 5-point Likert-type scale, where 1 ⫽ Extremely Uncharac-

teristic of Me and 5 ⫽ Extremely Characteristic of Me. The Anger

and Hostility subscales assess the emotional aspects of aggression.

In past work, anger has been associated with reactive and impul-

sive aggression, and hostility has been associated with premedi-

tated aggression (Stanford et al., 2003).

Adolescent and young adult inpatient sample. Measures

used in this study for evaluation of the BIS-Brief included the

IPAS (Stanford et al., 2003) and the BPAQ (Buss & Perry, 1992).

Here, we describe only the IPAS because the BPAQ was described

above. The IPAS is a 30-item measure that classifies an individ-

ual’s aggressive acts. The IPAS asks participants to consider their

aggressive acts over the past 6 months and then indicate their

agreement (from 5 ⫽ Strongly Agree to 0 ⫽ Strongly Disagree) for

each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Traditionally, a screening

question is used (“Over the past 6 months, have you had episodes

where you would become angry and enraged with other people and

acted in an aggressive way?”), and only participants who answer

affirmatively complete the IPAS items. In the present study, we

omitted the screening question so that all participants were asked

to respond to the entire IPAS. The scoring method for the IPAS

was recently revised to reflect new factor analysis findings and to

allow for a categorical and dimensional scoring approach (Stan-

ford, 2011). The new scoring method uses 18 of the 30 IPAS items.

A dimensional approach was used in the present study. Two

subscales are measured: Impulsive Aggression (10 items; e.g.,

“When angry, I reacted without thinking”) and Premeditated Ag-

gression (eight items; e.g., “I felt my outbursts were justified”). In

the dimensional approach, the sum of the item responses in each

subscale is calculated. The IPAS subscale scores had Cronbach’s

alphas of .92 and .85 for Impulsive and Premeditated, respectively.

Results

Adult community sample: Borderline versus normal

controls. Past research has shown that BPD is associated with

higher levels of impulsiveness compared with normal control

samples (Skodol, Gunderson, et al., 2002; Skodol, Siever, et al.,

2002). We performed two independent samples t tests to evaluate

the group differences in impulsiveness between those who met the

criteria for BPD and those who were free of both Axis I and Axis

II disorders. For those who met the criteria for BPD, reliability

estimated with Cronbach’s alpha was .84 and .81 for the 30-item

BIS-11 scores and the eight-item BIS-Brief scores, respectively.

For those free of both Axis I and Axis II disorders, reliability

estimates using Cronbach’s alpha were .81 and .73 for the 30-item

BIS-11 and the eight-item BIS-Brief, respectively. Impulsiveness

scores based on the 30-item BIS-11 showed significant group

mean differences, t(218) ⫽ 16.36, p ⬍ .001; individuals with BPD

had significantly higher scores (M ⫽ 79.63, SD ⫽ 12.02) com-

pared with normal controls (M ⫽ 54.99, SD ⫽ 8.88). These

differences were replicated with the eight-item BIS-Brief, t(227) ⫽

16.29, p ⬍ .001. The BPD group had significantly higher impul-

siveness scores (M ⫽ 21.77, SD ⫽ 4.15) compared with the normal

control group (M ⫽ 13.49, SD ⫽ 3.09). Thus, scores obtained with

the BIS-Brief are found to show the expected group differences in

impulsiveness previously demonstrated with scores based on the

entire 30-item BIS-11.

Adult domestic violence sample. Research has shown that

BIS-11 scores are related to scores obtained on measures of

aggression, hostility, anger, impulsive aggression, antisocial be-

havior, and BPD. We investigated whether the pattern of relation-

ships among these variables is replicated with the eight-item

BIS-Brief using an adult domestic violence sample. For this sam-

ple, reliability estimates using Cronbach’s alpha for the 30-item

BIS-11 scores and the eight-item BIS-Brief scores were .78 and

.74, respectively. Scores obtained on the BIS-11 and BIS-Brief

were divided by their respective numbers of items to place the

scores on the same scale prior to analysis. Table 5 presents the

means and standard deviations of the BIS-11 and the BIS-Brief

and their correlations with the BPAQ Physical Aggression, Verbal

Aggression, Anger, and Hostility subscales and the PAI Border-

line, Antisocial, and Aggression subscales (based on 90 respon-

dents with complete data on the measures). Scores obtained on

these measures that are significantly related to the BIS-11 scores

(i.e., BPAQ Physical, Anger, and Hostility subscales and PAI

Borderline, Antisocial, and Aggression subscales) are also signif-

Table 5

Domestic Violence Sample and Correlations of BIS-11 and BIS-Brief With Buss-Perry and PAI Subscales

Correlation

Measure M (SD) BP-Physical BP-Verbal BP-Anger BP-Hostility PAI-BOR PAI-ANT PAI-AGG

BIS-11 2.12 (0.35) .45 .19 .53 .41 .58 .49 .44

BIS-Brief 2.05 (0.57) .38 .16 .52 .33 .46 .38 .45

Note. BIS-11 ⫽ Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11; BIS-Brief ⫽ brief version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; BP ⫽ Buss-Perry Aggression

Questionnaire; PAI ⫽ Personality Assessment Inventory; BOR ⫽ Borderline subscale; ANT ⫽ Anti-Social subscale; AGG ⫽ Aggressive subscale. All

correlations are significant at p ⬍ .001, except correlations of BP-Verbal with BIS-11 and BIS-Brief, which are not significant.

222

STEINBERG, SHARP, STANFORD, AND THARP

icantly related to the BIS-Brief scores. Thus, the pattern of corre-

lations observed with the BIS-11 is replicated with the BIS-Brief.

Adolescent and young adult inpatient sample. We investi-

gated whether the pattern of correlations between measures of

aggression (verbal, physical, anger, hostility, impulsive, and pre-

meditated) and the BIS-11 is replicated with the BIS-Brief using

scores obtained from an adolescent and young adult inpatient

sample. For this sample, reliability estimates using Cronbach’s

alpha for the 30-item BIS-11 scores and the eight-item BIS-Brief

scores are .86 and .83, respectively. Before conducting the analy-

ses, the scores obtained on the BIS-11 and the BIS-Brief were

transformed to be on the same scale by dividing each respective

score by its number of items. Table 6 provides the means and

standard deviations of the BIS-11 and the BIS-Brief and their

correlations with the BPAQ subscales and the IPAS subscales

(based on 84 respondents with complete data on the measures). As

shown in the table, scores obtained on these measures that are

significantly related to the BIS-11 (i.e., BPAQ Physical, Verbal,

Anger, and Hostility subscales and the IPAS Impulsive subscale)

are also significantly related to the BIS-Brief. Thus, the relations

observed with the BIS-11 scores and scores from these measures

of aggression are mirrored with scores obtained with the BIS-

Brief.

Discussion

The first aim of the present study was to examine the established

three-factor structure of the BIS through a confirmatory multidi-

mensional IRT approach (Study 1). In anticipation of the shorten-

ing of the BIS, our second aim was to evaluate the construct

validity of scores obtained with the new shorter BIS by examining

its performance against the original 30-item BIS-11 version in

three samples (Study 2). In Study 1, we found that the BIS-11 item

set is multidimensional. However, close inspection of the pattern

of slope parameters show that the BIS-11 exhibits a type of

multidimensionality that is more LD than measurement of indi-

vidual differences on intended psychological constructs. In addi-

tion, fewer than half of the items had substantial slope parameters

on the general factor. These findings led us to develop a short

unidimensional version of the BIS comprised of eight of the

original 30 items.

Barratt originally conceptualized impulsiveness as a unidimen-

sional construct but later, based on the factor analytic studies,

became convinced that impulsiveness encompassed three subtraits

(attentional, motor, and non-planning; Stanford et al., 2009). Al-

though the BIS total sum score rather than subscale scores is most

often used, past research has shown meaningful differences using

these three subscales. For example, Swann et al. (2008) reported

correlations of the three subscales with a sample of patients with

mood disorders and found different relationships between BIS

subscales depending on affective state. Specifically, attentional

impulsiveness was related to both depression and mania, whereas

motor impulsiveness was related to mania, and non-planning im-

pulsiveness was related to depression. A question arises: If mean-

ingful differences like those presented in Swann et al. are found

with the subscale scores, then why were these not interpreted as

“constructs” in the bifactor model? As presented in Table 1, the

slope parameters for the three subscales, listed in columns a

2

–a

4

,

show that for each subscale, two items have substantial slopes,

whereas the remaining items have very small, albeit nonzero

slopes, indicating little relation of the item response to an under-

lying construct. The similarity of content of the items with sub-

stantial slopes on each subscale led to an interpretation of LD,

rather than a meaningful construct on which to measure individual

differences. So, the subscale differences are primarily due to

responses to the two questions with substantial loadings; the re-

maining items contribute some small systematic variability, but

mostly add to measurement error. Thus, the differences that Swann

et al. describe may be mostly a function of individual differences

in responses to the doublets found on each subscale. Although this

requires empirical investigation, it is possible that responses to

these item-doublets are differentially responsive depending on

clinical diagnosis.

In Study 2, we demonstrated similar indices of construct validity

for scores obtained on the BIS-Brief that is found with BIS-11 total

scores using a fraction of the items. Comparing a group diagnosed

with BPD with a normal control group, the BIS-Brief scores

showed the significant group mean difference that was observed

with the BIS-11. In an adult domestic violence sample, the pattern

of correlations of scores obtained with the BIS-11 with measures

of aggression, BPD, and antisocial behavior were replicated with

the BIS-Brief. Using data collected at an inpatient sample of

adolescents and young adults, the pattern of correlations of the

BIS-11 with measures of aggression and impulsive aggression

were found with the BIS-Brief. Our evidence of construct validity

implies that across three different samples and diverse age ranges,

the scores obtained on the BIS-Brief show similar group differ-

ences and patterns of correlations that are observed with the

original 30-item BIS-11 total score. Thus, the eight-item unidi-

mensional BIS-Brief allows for the measurement of impulsiveness

with greater efficiency. This will be useful in clinical assessment

Table 6

Adolescent and Young Adult Inpatient Sample, Correlations of BIS-11 and BIS-Brief With Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire, and

Impulsive Premeditated Aggression Scale

Correlation

Measure M (SD) BP-Physical BP-Verbal BP-Anger BP-Hostility IPAS-Impulsive IPAS-Premeditated

BIS-11 2.43 (0.43) .39 .49 .41 .62 .46 .20

BIS-Brief 2.57 (0.65) .34 .48 .36 .53 .37 .17

Note. BIS-11 ⫽ Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11; BIS-Brief ⫽ brief version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; BP ⫽ Buss-Perry Aggression

Questionnaire; IPAS ⫽ Impulsive Premeditated Aggression Scale. All correlations are significant at p ⫽ .001 or less, except correlations of IPAS-

Premeditated with BIS-11 and BIS-Brief, which are not significant.

223

BARRATT IMPULSIVENESS SCALE–BRIEF

settings as well as large epidemiological studies or intervention

trials of psychiatric disorders.

The findings of the present study have implications for the

conceptualization of impulsiveness. Specifically, a question re-

mains regarding the utility of the cognitive, motor, and non-

planning components of impulsivity. Although our analyses did

not support this conceptualization, variations in the nature of

impulsivity may exist across clinical disorders similar to those

reported in Swann et al. (2008). Although the BIS-11 is not the

most useful instrument to use when examining such variation, it is

possible that instruments specifically designed to measure the

more narrowly defined components of impulsiveness may detect

what differences, if any, exist in impulsiveness across clinical

disorders.

The present study also has implications for the measurement of

psychological constructs. Many instruments presently in use in

clinical, personality, and other areas of psychology were devel-

oped in the 1960s and 1970s and are quite lengthy. At that time,

reliability was a first consideration, and one strategy for increasing

reliability is to increase the number of items. This focus on

reliability leads to the inclusion of many items, some of which are

likely to be repetitious (and this can now be diagnosed with large

LD indices). In addition, when writing items, it becomes increas-

ingly difficult to generate good items; thus, as more items are

written, they are likely to stray from the central theme of the

construct. Present methodology allowed us to (a) distinguish LD

from substantive constructs and (b) reduce the length of the in-

strument by selecting items on the basis of IRT item parameters

and content considerations without loss of information.

One of the implications from this research is that clinical,

personality, and other areas of psychology that rely on the mea-

surement of psychological constructs may benefit if analyses sim-

ilar to that undertaken with the BIS-11 were conducted with many

of the instruments presently in use. Such instruments can poten-

tially be made much shorter. In addition, the evaluation of con-

struct validity of the shorter measure is facilitated because existing

data can be used to compare the mean differences or relationships

between original instruments with other relevant variables and

investigate whether the same group differences or relationships are

observed with new short measures. However, this strategy has its

limitations; for example, this approach precludes any revisions or

additions to the original set of items. As noted previously, some

BIS-11 items were eliminated because the meaning of the item

either drifted from its 1969 meaning (e.g., “I plan for job security”)

or the item lost meaning (e.g., “I am a steady thinker”). Depending

on an evaluation of item quality, for some instruments, it might be

better to develop a measure that includes both legacy items as well

as newly written items. In these cases, new investigations of

evidence of construct validity would be required.

Limitations

The BIS-Brief provides researchers with a short unidimensional

assessment of general impulsiveness that will be particularly use-

ful when the number of questions must be limited, as in large

epidemiological studies, clinical assessment settings, and other

research in which reduction in time and burden on respondents is

desired. The eight-item BIS-Brief score has reliability estimates

comparable to the 30-item BIS-11 total score and shows similar

evidence of construct validity. Notwithstanding these strengths, it

should be noted that use of the BIS-Brief, because it is a unidi-

mensional measure of general impulsiveness, precludes investiga-

tion of the utility of the more narrowly conceptualized specific

components of impulsiveness (e.g., cognitive, planning, behavior).

Much research has been conducted that conceptualizes impulsive-

ness as multidimensional, thus not preserving the specific factors

in the BIS-Brief may limit its usefulness; for example, predictive

relationships that differ among the specific components cannot be

detected by such a general measure. Our goal was to retain a short

form of a general impulsiveness scale, rather than a more specific

or multidimensional scale. Research focused on specific compo-

nents of impulsiveness will require additional measures.

In conclusion, the BIS has had a long and dynamic develop-

mental history (Patton & Stanford, 2011). Originally containing 80

true–false items (Barratt, 1959), the instrument has changed dra-

matically over its 11 revisions. Barratt’s goal was always to

develop the most psychometrically reliable and valid instrument

possible. We see the present study and the BIS-Brief as a contin-

uation of that long developmental process. We suggest that the

BIS-Brief not be seen as a replacement for the BIS-11, but rather

a refinement of the scale much like the BIS-11 was an improve-

ment over its predecessor the BIS-10 (Barratt, 1985). It is our hope

that this next step in the development of the BIS will facilitate even

more work with the instrument for years to come.

References

Ainslie, G. (1975). Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsiveness

and impulse control. Psychological Bulletin, 82, 463– 496. doi:10.1037/

h0076860

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical man-

ual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barratt, E. S. (1959). Anxiety and impulsiveness related to psychomotor

efficiency. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 9, 191–198. doi:10.2466/pms

.1959.9.3.191

Barratt, E. S. (1985). Impulsiveness subtraits: Arousal and information

processing. In J. T. Spence & C. E. Izard (Eds.), Motivation, emotion,

and personality (pp. 137–146). North Holland, the Netherlands:

Elsevier.

Barratt, E. S., Stanford, M. S., Kent, T. A., & Felthous, A. (1997).

Neuropsychological and cognitive psychophysiological substrates of

impulsive aggression. Biological Psychiatry, 41, 1045–1061. doi:

10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00175-8

Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and

pathological gambling. Addiction, 97, 487– 499. doi:10.1046/j.1360-

0443.2002.00015.x

Brady, K. T., Myrick, H., & McElroy, S. (1998). The relationship between

substance use disorders, impulse control disorders, and pathological

aggression. American Journal of Addiction, 7, 221–230.

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. P. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452– 459. doi:10.1037/0022-

3514.63.3.452

Cai, L., du Toit, S. H. C., & Thissen, D. (2011). IRTPRO: Flexible,

multidimensional, multiple categorical IRT modeling [Computer soft-

ware]. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International.

Cai, L., Maydeu-Olivares, A., Coffman, D. L., & Thissen, D. (2006).

Limited information goodness-of-fit testing of item response theory

models for sparse 2

p

tables. British Journal of Mathematical and Sta

-

tistical Psychology, 59, 173–194. doi:10.1348/000711005X66419

224

STEINBERG, SHARP, STANFORD, AND THARP

Cai, L., Yang, J. S., & Hansen, M. (2011). Generalized full-information

item bifactor analysis. Psychological Methods, 16, 221–248. doi:

10.1037/a0023350

Chen, W.-H., & Thissen, D. (1997). Local dependence indices for item

pairs using item response theory. Journal of Educational and Behavioral

Statistics, 22, 265–289.

de Wit, H. (2009). Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug

use: A review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology, 14, 22–31.

doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (2002).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV–TR Axis I Disorders: Re-

search version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics

Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response

theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350 –365. doi:10.1037/0022-

3514.78.2.350

Gibbons, R. D., Weiss, D. J., Kupfer, D. J., Frank, E., Fagoilini, A.,

Grochocinski, V. J.,...Immekus, J. C. (2008). Using computerized

adaptive testing to reduce the burden of mental health assessment.

Psychiatric Services, 59, 361–368. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.59.4.361

Gray, J. A. (1987). Perspectives on anxiety and impulsivity: A commen-

tary. Journal of Research in Personality, 21, 493–509. doi:10.1016/

0092-6566(87)90036-5

Gray-Little, B., Williams, V. S. L., & Hancock, T. D. (1997). An item

response theory analysis of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Person-

ality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 443– 451. doi:10.1177/

0146167297235001

Houston, R. J., & Stanford, M. S. (2005). Electrophysiological substrates

of impulsiveness: Potential effects on aggressive behavior. Progress in

Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 29, 305–313.

doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.016

Ireland, J. L., & Archer, J. (2008). A confirmatory factor analysis study of

the Barratt Impulsivity Scale. Personality and Individual Differences,

45, 286 –292. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.04.012

Jacobo, M. C., Blais, M. A., Baity, M. R., & Harley, R. (2007). Concurrent

validity of the Personality Assessment Inventory borderline scales in

patients seeking dialectical behavior therapy. Journal of Personality

Assessment, 88, 74 –80.

King-Casas, B., Sharp, C., Lomax, L., Lohrenz, T., Fonagy, P., & Mon-

tague, R. (2008, August 8). The rupture and repair of cooperation in

borderline personality disorder. Science, 321, 806 – 810. doi:10.1126/

science.1156902

Kurtz, J. E., Morey, L. C., & Tomarken, A. J. (1993). The concurrent

validity of three self-report measures of borderline personality. Journal

of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 15, 255–266.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer

agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159 –174. doi:10.2307/

2529310

Lejuez, C. W., Magisdson, S. H., Mitchell, R. S., Stevens, M. C., & de Wit,

H. (2010). Behavioral and biological indicators of impulsivity in the

development of alcohol use, problems, and disorders. Alcoholism: Clin-

ical and Experimental Research, 34, 1334–1345.

Links, P. S., Heslegrave, R., & van Reekum, R. (1999). Impulsivity: Core

aspect of borderline personality. Journal of Personality Disorders, 13,

1–9. doi:10.1521/pedi.1999.13.1.1

Logan, G. D. (1994). On the ability to inhibit thought and action: A user’s

guide to the stop signal paradigm. Dagenback, and T. H. Carr (Eds.),

Inhibitory processes in attention, memory, and language (pp. 189–239).

San Diego,CA: Academic Press.

Loranger, A. W., Susman, V. L., Oldham, J. M., & Russakoff, L. M.

(1987). The Personality Disorder Examination: A preliminary report.

Journal of Personality Disorders, 1, 1–13. doi:10.1521/pedi.1987.1.1.1

Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Joe, H. (2005). Limited and full information

estimation and goodness-of-fit testing in 2n contingency tables: A uni-

fied framework. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 100,

1009 –1020. doi:10.1198/016214504000002069

Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Joe, H. (2006). Limited information goodness-of-

fit testing in multidimensional contingency tables. Psychometrika, 71,

713–732. doi:10.1007/s11336-005-1295-9

Meda, S. A., Stevens, M. C., Potenza, M. D., Pittman, B., Gueorguieva, R.,

Andrews, M. M.,...Pearlson, G. D. (2009). Investigating the behavioral

and self-report constructs of impulsivity domains using principal com-

ponent analysis. Behavioral Pharmacology, 20, 390 –399. doi:10.1097/

FBP.0b013e32833113a3

Moeller, F. G., Barratt, E. S., Dougherty, D. M., Schmitz, J. M., & Swann,

A. C. (2001). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 158, 1783–1793. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783

Morey, L. C. (1991). Personality assessment inventory. Lutz, FL: Psycho-

logical Assessment Resources.

Morey, L. C., Waugh, M. H., & Blashfield, R. K. (1985). MMPI scales for

DSM–III personality disorders: Their derivation and correlates. Journal

of Personality Assessment, 49, 245–251. doi:10.1207/

s15327752jpa4903_5

Nigg, J. T. (2003). Response inhibition and disruptive behaviors: Toward

a multiprocess conception of etiological heterogeneity for ADHD com-

bined type and conduct disorder early-onset type. Annals of the New

York Academy of Sciences, 1008, 170 –182. doi:10.1196/annals.1301

.018

Patel, A., Sharp, C., & Fonagy, P. (2011). Criterion validity of the MSI-

BPD in a community sample of women. Journal of Psychopathology

and Behavioral Assessment, 33, 403–408. doi:10.1007/s10862-011-

9238-5

Patton, J. H., & Stanford, M. S. (2011). Psychology of impulsivity. In J.

Grant & M. Potenza (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of impulse control

disorders (pp. 262–278). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure

of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology,

51, 768–774. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6⬍768::AID-

JCLP2270510607⬎3.0.CO;2-1

Reynolds, B., Ortengren, A., Richards, J. B., & de Wit, H. (2006). Dimen-

sions of impulsive behavior: Personality and behavioral measures. Per-

sonality and Individual Differences, 40, 305–315. doi:10.1016/j.paid

.2005.03.024

Samejima, F. (1969). Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern

of graded scores. Psychometric Monograph Supplement, 34(4, Pt. 2).

Samejima, F. (1997). Graded response model. In W. J. van der Linden &

R. K. Hambleton (Eds.), Handbook of item response theory (pp. 85–

100). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Sharp, C., Ha, C., & Fonagy, P. (2011). Get them before they get you:

Trust, trustworthiness and social cognition in boys with and without

externalizing behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology,

23, 647– 658. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000003

Skodol, A. E., Gunderson, J. G., Pfohl, B., Widiger, T. A., Livesley, W. J.,

& Siever, L. J. (2002). The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology,

comorbidity, and personality structure. Biological Psychiatry, 51, 936–

950. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01324-0

Skodol, A. E., Siever, L. J., Livesley, W. J., Gunderson, J. G., Pfohl, B., &

Widiger, T. A. (2002). The borderline diagnosis II: Biology, genetics,

and clinical course. Biological Psychiatry, 51, 951–963. doi:10.1016/

S0006-3223(02)01325-2

Spinella, M. (2007). Normative data and a short form of the Barratt

Impulsiveness Scale. International Journal of Neuroscience, 117, 359 –

368. doi:10.1080/00207450600588881

Stanford, M. S. (2011). Procedures for the classification of aggressive/

violent acts. Unpublished manuscript.

225

BARRATT IMPULSIVENESS SCALE–BRIEF

Stanford, M. S., Houston, R. J., & Baldridge, R. M. (2008). Comparison of

impulsive and premeditated perpetrators of intimate partner violence.

Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 26, 709 –722. doi:10.1002/bsl.808

Stanford, M. S., Houston, R. J., Mathias, C. W., Villemarette-Pittman,

N. R., Helfritz, L. E., & Conklin, S. M. (2003). Characterizing aggres-

sive behavior. Assessment, 10, 183–190.

Stanford, M. S., Mathias, C. W., Dougherty, D. M., Lake, S. L., Anderson,

N. E., & Patton, J. H. (2009). Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness

Scale: An update and review. Personality and Individual Differences,

47, 385–395. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.008

Steinberg, L. (1994). Context and serial-order effects in personality mea-

surement: Limits on the generality of measuring changes the measure.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 341–349. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.341

Steinberg, L. (2001). The consequences of pairing questions: Context

effects in personality measurement. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 81, 332–342. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.332

Steinberg, L., & Thissen, D. (1996). Uses of item response theory and the

testlet concept in the measurement of psychopathology. Psychological

Methods, 1, 81–97. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.81

Swann, A. C., Steinberg, J. L., Lijffijt, M., & Moeller, F. G. (2008).

Impulsivity: Differential relationship to depression and mania in bipolar

disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 106, 241–248. doi:10.1016/j

.jad.2007.07.011

Thissen, D. (2009). The MEDPRO project: An SBIR project for a com-

prehensive IRT and CAT software system—IRT software. In D. J. Weiss

(Ed.), Proceedings of the 2009 GMAC Conference on Computerized

Adaptive Testing. Retrieved from www.psych.umn.edu/psylabs/

CATCentral/

Thissen, D., & Steinberg, L. (2010). Using item response theory to disen-

tangle constructs at different levels of generality. In S. Embretson (Ed.),

Measuring psychological constructs: Advances in model-based ap-

proaches (pp. 123–144). Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association. doi:10.1037/12074-006

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The Five Factor Model and

impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand im-

pulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669– 689. doi:

10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7

Yung, Y. F., McLeod, L. D., & Thissen, D. (1999). On the relationship

between the higher-order factor model and the hierarchical factor model.

Psychometrika, 64, 113–128. doi:10.1007/BF02294531

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Sickel, A. E., & Yong, L. (1996). The

Diagnostic Interview for DSM–IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV).

Belmont, MA: McLean Hospital, Laboratory for the Study of Adult

Development.

Zanarini, M. C., Vujanovic, A., Parachini, E. A., Boulanger, J. L., Fran-

kenburg, F. R., & Hennen, J. (2003). A screening measure for BPD: The

McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder

(MSI-BPD). Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 568 –573. doi:

10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355

Received September 19, 2011

Revision received August 1, 2012

Accepted August 6, 2012 䡲

226

STEINBERG, SHARP, STANFORD, AND THARP